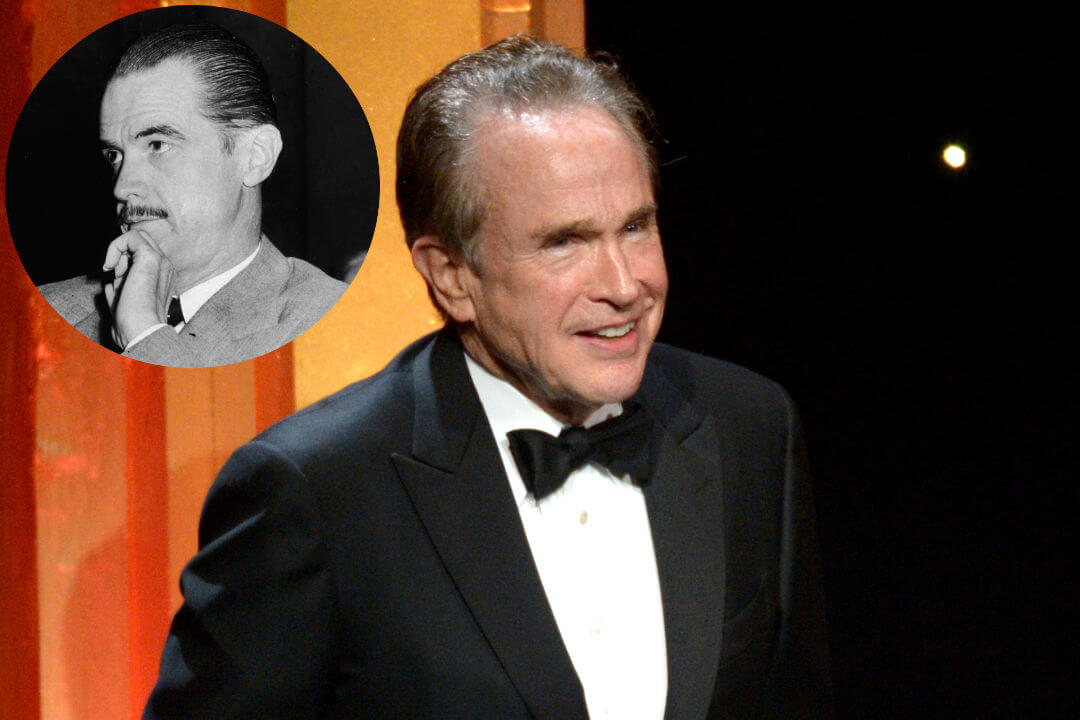

For many years Warren Beatty had wanted to do a movie about Howard Hughes. According to various reports, he had dallied with the idea since the seventies. Because Beatty has produced and directed some distinguished films, most of us who heard about this project had some high expectations for it. An accomplished and intelligent Hollywood film-maker was going to take on a fascinating and complex American historical figure, about whom much mystery and fascination have existed. In fact, one could argue that Hughes was the most famous and controversial American billionaire before Donald Trump. Except he was much richer than Trump. To give one example: when Hughes Aircraft was auctioned off in 1985—about a decade after Hughes’s death—it sold for $5.2 billion.

Trump, early in his career, actually thought of going into the movie business. He then optioned for real estate. Hughes actually did go into the movie business for about a twenty-year period. After that, he became a major real estate investor in the Las Vegas area. As Trump did in Atlantic City, Hughes purchased several hotel-casinos.

|

| CIA counterintel tsar James Angleton |

But in many ways, Hughes’ life and career is much more interesting, complex, and puzzling than Trump’s. In fact, the last part of Hughes’ life is so mysterious that, to this day—over forty years after his death—writers are still trying to figure out the last ten years of it. All one needs to know as to why the mystery exists is this little known fact: Although there is no evidence that Hughes actually met James Angleton, the legendary CIA counter-intelligence chief attended Hughes’ funeral.

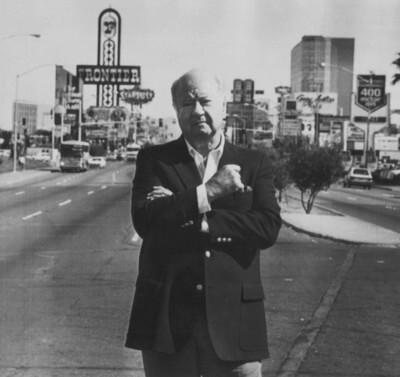

|

| Robert Maheu in Las Vegas |

CIA agent Robert Maheu—who ran Hughes’ Nevada holdings for four years—once said about him that Hughes wanted to “set himself into an alliance with the CIA that would protect him from investigation by government agencies.” (Playboy, September , 1976, “The Puppet and the Puppetmasters”, by Laurence Gonzales and Larry DuBois) After Maheu was unceremoniously expelled from his position as Hughes’ manager in Nevada at the end of 1970, the CIA found a way to mitigate Hughes’ fear about government inquiries. They secretly contracted out with Hughes for something called Project Jennifer. This was a top secret operation that was budgeted at about $350 million. The idea was to build a huge salvage ship that would surface a sunken Russian submarine in the Pacific about 700 miles from Hawaii. At that time, it was one of the largest contracts for a single national security item the CIA had ever extended. This, of course, allowed the Agency to plant agents inside the company.

But this was only a rather small part of the cross-pollination of Hughes companies with the CIA. On April 1, 1975, The Washington Post reported that “Hughes Aircraft had been mentioned as a potential hotbed of interrelationships with the CIA.” For the simple reason that “Hughes gravitated into areas that other people refused to go into or didn’t believe in.” (op. cit. DuBois and Gonzales) This allowed the CIA to negotiate with Hughes for many of their black budget items. Time magazine once reported that, in the last ten years of his life, the CIA had contracted out about six billion dollars worth of this kind of work to Hughes. This is why, as more than one investigator has noted, at times it was difficult to know where the Hughes empire ended and the CIA began.

This problem did not just exist with Hughes Aircraft, but also with Hughes Tool Company, whose chief asset was an oil drill bit which cracked through rock in record time. This device was invented by Hughes’ father, but he refused to market it, preferring to patent and then lease it. It was a sensational success, both nationally and internationally. As one source revealed, the information garnered from these leases became an important part of the Hughes/CIA relationship because of the Agency’s interest in resource-recovery information. Other countries could not keep the true value of their petroleum resources secret anymore. (ibid)

|

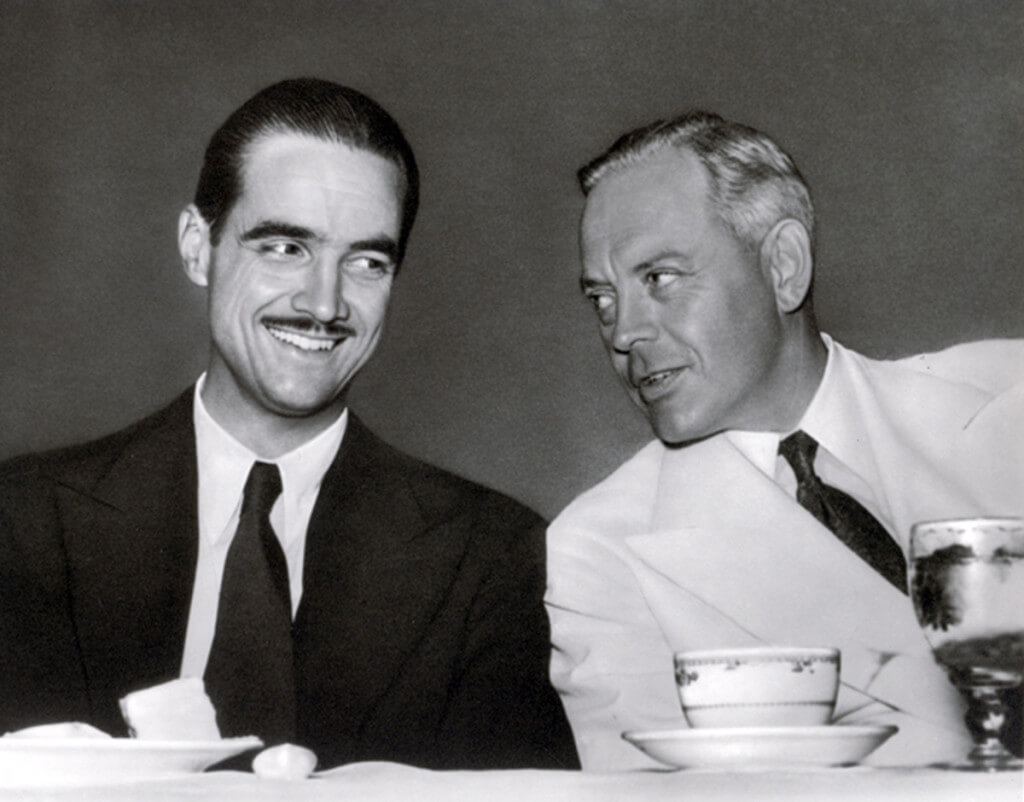

| Bebe Rebozo with Nixon |

Even Hughes Medical Institute was not immune to this melding of interests. HMI was originally set up in 1953 in Florida with much fanfare. Hughes announced it would be a great research institute that would benefit all mankind. In reality, it was a tax dodge scheme. Much of the profits from Hughes Aircraft were funneled through HMI. Now Hughes would not have to pay taxes on them since HMI was designed as a tax exempt charity, with Hughes as the sole trustee. But by the late sixties, as Hughes became more eccentric, incapacitated, and cut off from the outside world, and as his interests became entwined with the Agency, there were reports that HMI became a CIA front. One Pentagon official told Time words to that effect. When, on instructions from Hughes, employee John Meier went on a visit to HMI in 1969, he learned the same thing from HMI president Ken Wright. He also learned that Wright was siphoning off money to Richard Nixon’s close friend Bebe Rebozo. (Lisa Pease, “Howard Hughes, John Meier, Don Nixon and the CIA”, Probe Magazine, January-February 1996) All these instances, and more, explain why Angleton was quite appreciative of the opportunities Hughes gave the Agency to extend its reach and power. In fact, the role of Hughes with the Agency was joked about in the halls of Langley. There, they referred to Hughes as “The Stockholder”. (Jim Hougan, Spooks, p. 259)

We should add one more notable point about this particular issue. Most commentators seem to agree that a central crossroads in Hughes’ life and career was a mysterious journey that he made to Boston in 1966. While in Boston, he stayed at the Ritz-Carlton. But he also visited a hospital whose physician in chief was George Thorn, a director of Hughes Medical Institute. (Howard Hughes: His Life and Madness, by Donald Bartlett and James Steele, p. 276) To this day, no one knows the purpose of this trip, why Hughes was in the hospital, or what was done to him there. But in addition to Thorn’s presence, the security for the Boston journey was arranged by CIA agent Robert Maheu. (ibid, p. 275) It was after this that Hughes made the decision to move his empire to Nevada, and he also went into a state of near hibernation. He moved into the top floor of the Desert Inn hotel and began to inject himself with large liquid doses of codeine and Valium.

|

| Hughes parade after his around-the-world flight (1938) |

In addition to all the above intrigue, Hughes was a movie producer and director for a period of about twenty years. After he lost interest in films, he still ran the RKO studio as a kind of absentee owner until the fifties, when he sold it. He was a record-breaking airplane pilot. In 1935, piloting a plane he himself commissioned, he easily smashed the prevailing air speed record. In 1936 and 1937, he set four consecutive records for transcontinental flight times. (Bartlett and Steele, pp. 82-87) In 1938 Hughes cut Charles Lindbergh’s flight time from New York to Paris in half. That same year, as part of the same flight, Hughes did the same with the late Wally Post’s round the world flight. (ibid, pp. 94-97) For that achievement Hughes and his four-man crew received a ticker tape parade down Broadway that rivaled Lindbergh’s.

|

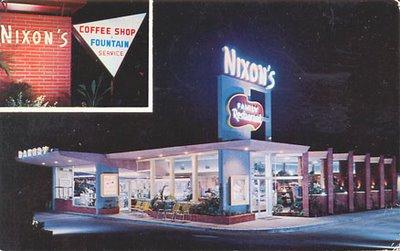

| Donald Nixon's diner |

Then there was Hughes’ relationship with Richard Nixon. The Internal Revenue Service recognized that Hughes had set up a tax scam with HMI, and refused to give the so-called medical center the necessary tax exemption. So Hughes did what he became famous for: he found a way to grease a politician’s palm. Except, in this case, it was the politician’s brother. Donald Nixon was having problems with a business enterprise called Nixonburgers—a combination fast food venture and shopping center. He was tendered a loan for over two hundred thousand dollars—well over a million today. The loan came from Hughes. It was extended in December of 1956, a month after the presidential election in which President Dwight Eisenhower and Vice-President Richard Nixon were re-elected. The loan was secured by a plot of land in Whittier, California—except the lot was worth, at most, about $50,000. Once the transaction was completed, Hughes headquarters in Hollywood notified the Vice-President all was in place for his brother Donald. (ibid, p. 204) That phone call was made in February of 1957. On March 1st, the IRS reversed its decision about Hughes Medical Center: the tax dodge scheme was now made legal.

|

| Actress Jean Peters |

|

| Hughes & Noah Dietrich |

In the late fifties, Hughes began to struggle with his personal demons and galloping eccentricities. One of America’s richest and most powerful men called an old friend in Texas and told him he had ruined his life beyond repair. (ibid, p. 225) For instance, his marriage to actress Jean Peters in 1957 seems to have been a marriage of convenience. Hughes thought that his long time employee, Noah Dietrich, was plotting to have him declared incompetent so as to appoint a conservator over his affairs. Once married, this could not be done unless Peters approved it. (Beatty refers to this aspect more than once in his film) So, after 32 years, Hughes ended up firing Dietrich. There was reason for Hughes to fear such a coup. For example, when once facing a financial crisis with TWA, he lived and worked out of a screening room in West Hollywood for months. (ibid, p. 231) Unlike the depiction in the Martin Scorsese/Leonardo DiCaprio film, The Aviator, it appears it was at this time that he began to act bizarrely: walking around nude, spending hours in the bathroom, refusing to touch doorknobs etc. He also became addicted to drugs, e.g., painkillers like codeine and sedatives like Valium.

|

| The TWA Constellation, which Hughes requested Lockheed to build |

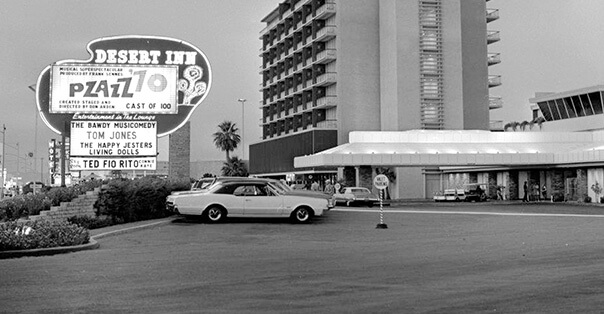

After losing control of TWA in 1965, Hughes decided to sell his stock in that company. That transaction, worth well over a half billion dollars, was one of the largest single stock sales in history up to that time. To lower his taxes, he then decided to move to Las Vegas. He promptly purchased both the Desert Inn and the Sands hotel casinos in 1967. Shortly after, he purchased the Castaways, the Landmark, and the Frontier hotels plus the Silver Slipper casino. He also bought a local TV station. As with his Nixon bribe, he then assigned a lawyer on his staff to run envelopes full of cash to scores of politicians in the state, both Democrats and Republicans. (ibid, p. 344) Hughes had designs on buying every major hotel-casino on the Las Vegas Strip, and then extending his empire north to Reno and Lake Tahoe. For all intents and purposes, he was going to own Nevada.

|

| The Desert Inn (1967) |

He made one mistake. He had moved too far too fast. He had Nevada pretty much sewn up; even Governor Paul Laxalt was in his corner. (ibid, p. 307) But after the TWA stock sale he was now billed as the richest man in America. And he now seemed intent on using that money to buy Las Vegas. When word leaked out he was going to buy the Stardust, the Justice Department stepped in: If that sale was announced they would file suit on anti-monopoly grounds. This was anathema to Hughes, because it would necessitate him appearing in court—which he would never do.

Once his plans to take over the state were neutralized, Hughes’ life entered its final, almost surreal chapter. It is so strange, so fantastic, that it has generated a surfeit of controversy. In 1970, Jean Peters began divorce proceedings against Hughes. His behavior now began to get even more bizarre: for instance, he began to urinate into glass bottles and then cap them. (ibid, p. 426) Rumors of a palace coup based on declaring Hughes incompetent again began to swirl. This time they were spread by Maheu about Bill Gay, the head of Hughes operations in Los Angeles. Hughes now moved out of his penthouse at the Desert Inn and, for no apparent reason, relocated to Paradise Island in the Bahamas. He then moved from the Bahamas to Nicaragua, to London, to Vancouver, to Acapulco. Hughes reportedly passed away in Mexico and his body was flown to his hometown of Houston in April of 1976.

With the size, scope and drama of this kind of life and career, the subject of Hughes has provoked dozens of essays, books, and even novels; for example, Harold Robbins’ pulp novel, The Carpetbaggers, which was later made into a movie. Much of this output was generated after he passed away. In addition to more than one full length biography, there have been books devoted solely to Hughes’ actions in Hollywood, or in Las Vegas. There have been four films I know of that have dealt with Hughes either as the major character or a supporting figure. Jonathan Demme’s 1980 film Melvin and Howard deals with the much questioned incident between Hughes and one Melvin Dummar, who claimed to have picked up Hughes on a highway in Nevada and driven him to the Desert Inn. Years later, a Hughes will was discovered in a Mormon church in Salt Lake City. It left Dummar $150 million. But in 1978, a jury declared that the will was invalid.

To my knowledge, there have been two films made strictly about Hughes. In 1977 Tommy Lee Jones starred in a four-hour television mini-series entitled The Amazing Howard Hughes, which was based upon Noah Dietrich’s 1972 book. This is the only film I know that tries to trace the entire arc of Hughes’ adult life. In 2004, Martin Scorsese directed The Aviator starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Hughes. This film was a hundred million dollar super production that concentrated on Hughes in Hollywood. It made liberal use of dramatic license. Especially near the end where it portrayed the extreme symptoms of Hughes’ dementia about ten years earlier than they actually occurred—and impacting events they did not impact.

|

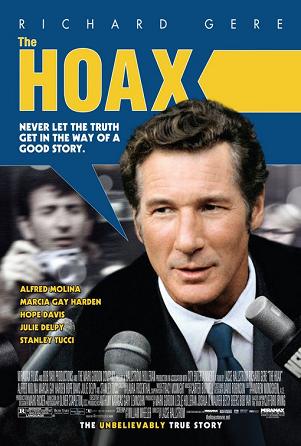

| The Hoax (2006) |

|

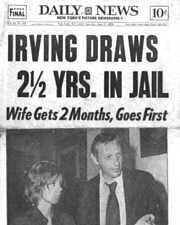

In 2006, Lasse Hallstrom directed Richard Gere as author Clifford Irving in The Hoax. That film depicts the episode where Irving attempts to pass off a manuscript he wrote about Hughes as being based upon hundreds of hours of private interviews he did with the reclusive billionaire. Irving sold the book to McGraw-Hill for over $700,000. The publisher did not go far enough in testing Irving or the manuscript, for Irving had never even met Hughes, let alone interviewed him. He had procured the manuscript of the Dietrich book and used that for much of his work. The caper later unraveled when it was discovered that Irving’s wife had deposited checks the publisher made out for Hughes into her personal bank account in Switzerland.

Warren Beatty’s current Hughes film begins with a fictionalized version of the Irving affair. In reality, Hughes made his famous phone call contesting the book from the Bahamas to a Hollywood sound stage at Universal Studios. The much ballyhooed event was televised live. Hughes had issued a press release saying he had nothing to do with the Irving manuscript, which had generated significant publicity well before it was printed. Therefore seven reporters had gathered on stage, along with an eighth person who was a Hughes PR official. The reporters—like James Bacon and Vernon Scott—had all covered Hughes extensively. They were there to hear the man’s voice and ask him questions about his past that he should have been able to recall. And they would use these to see if it was really Hughes on the line and to measure his denials about the book. Considering the fact he was under the high dosages of Valium and codeine injected into his body via syringe, Hughes did fairly well. But there were still certain questions that he could not answer, and these left malingering questions about the book. Those were later dashed by the discovery of the spouse’s foreign bank deposits.

|

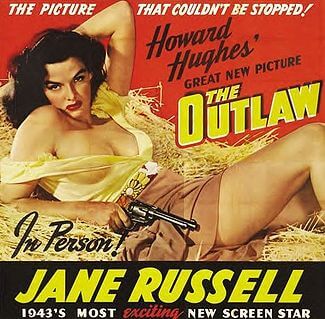

Beatty’s film, entitled Rules Don’t Apply, fictionalizes the phone call. It treats it as a complete triumph. It subtitles the scene as taking place in 1964 and the call being from Acapulco. Also, the purported autobiography has now become a novel which claims Hughes has amnesia and cannot recall the last five years of his life. From here, the film flashes backwards in time to the very end of Hughes’ film career to pick up the main body of the story. Towards the end of that part of his life—and for a few years after—Hughes had a curious habit. He had made stars out of relative unknowns Jean Harlow and Jane Russell in, respectively, Hell’s Angels and The Outlaw. From these promotions Hughes apparently thought he had the Midas touch with young starlets. For even though he was not really active in the movie business, he would send employees of his, like Maheu, out as talent scouts to say, a Miss America contest. They would sign up one or two young ladies and Hughes would pay for certain dancing, singing, and drama classes.

This was a very minor part of Hughes’ career, and most serious biographers deal with it in, perhaps, a page or so. But Beatty has made it the fulcrum of his film. After the movie’s prelude, with Hughes preparing for the live phone call about the ersatz book, he begins the film proper with a mother and daughter arriving in Los Angeles after being signed by a Hughes agent. The mother gets tired of waiting around and tells the daughter Hughes is playing around with her. The mother (played by Beatty’s wife Annette Bening) then leaves.

|

| Gail Ganley |

The girl that the story concentrates on is named Maria Mabrey. I assume, because of the use of alliteration in the name, that this character was based upon a woman named Gail Ganley. Ganley was a promising singer who was signed by Hughes, given acting classes, and told to keep her deal with Hughes a secret. She was promised $450 a week, plus expenses, and a future contract with Hughes. A driver transported her to her lessons each day in a Hughes auto. She was to keep the arrangement secret from everyone except those in her immediate family. And she was also to hold herself ready for a meeting with Hughes about her career. But as weeks dragged into months, none of what she was promised—the weekly salary, or the Hughes contract—actually materialized. When she complained about the delay she was put off by being told that Hughes was simply too busy at this time to deal with her—but he would in the future. She finally raised such a ruckus that she was told to drive to the Hughes headquarters at 7000 Romaine in Hollywood. She did and, as instructed, she honked her horn three times. On cue, a window flew open from the second floor. A man lowered an envelope with money in it by a string. This action was repeated a couple of times, but Ganley never got her contract. She later sued and received an out of court settlement. This weird ritual then ended. (Bartlett and Steele, pp. 243-44)

|

| The "Spruce Goose" |

The story progresses through a relationship developed between Mabrey (played by Lily Collins) and her driver, a character named Frank Forbes (Alden Ehrenreich). Like Ganley, Mabrey begins to complain about the lack of progress with her career. Frank tells her about a plot of land he wants to develop with another Hughes employee named Levar Mathis (Matthew Broderick). Frank , who is engaged, begins to lose interest in his fiancée and gets entangled emotionally with Mabrey. Frank hopes to interest Hughes in his land deal. One night he drives Hughes to see the infamous Spruce Goose in Long Beach. On the way Hughes reminds him that his employees should not be having relationships with each other (hence the film’s title).

Noah Dietrich (Martin Sheen) tells Hughes that he is beginning to act eccentrically—he is forgetful and repeating phrases. Hughes suspects Dietrich is plotting against him in order to have him declared incompetent. So he fires him and promotes Forbes. Mabrey then meets with Hughes, and in a rather odd scene, she starts crying and drinking, and he then proposes to her. The two get carried away and have sex. This happens while a Wall Street banker is calling Hughes, trying to see him about saving his investment in TWA.

Mabrey gets pregnant and tells Hughes, who does not believe her and thinks she is out for his money. She and Frank have an argument about Hughes with her saying that her mother was right about him using people. Hughes then says he wants to travel the world, so the film actually does a flash-forward. We see Hughes with Frank and Levar in Nicaragua, and then London—where Hughes pilots a plane. (This really happened and is one of the very last times anyone in the outside world saw Hughes.) While in Nicaragua, Hughes is informed the U.S. government is suing him for $645 million. He is then advised by one of his attorneys that he must sell Hughes Tool Company—founded by his father—to pay for it.

The film then returns to the phone call. Maria arrives with her son, who wanders around the suite and into Hughes’ bedroom. Hughes does not recognize him. On the phone he tells the reporters he has never met or seen the author of the book. Frank now decides to quit his job. He runs after Maria and the two, including Hughes’ son, leave the eccentric billionaire forever.

As noted previously, Beatty had contemplated doing a film about Hughes for a long time. Because of that, plus the fact that Beatty has made some distinguished historical films, many had high hopes for this film. Consider his track record in this regard. In 1967 he produced and acted in Bonnie and Clyde, which is both a classic and a milestone in American film history. In 1981 he produced, co-wrote, starred in and directed Reds, a moving chronicle about the life of American journalist John Reed. In 1991, he co-produced and starred in Bugsy, an entertaining and well-acted film about gangster Benjamin Siegel and the creation of Las Vegas. He also starred in The Parallax View in 1974, a tense, taut thriller about the assassinations of the sixties.

But in the last thirty years, Beatty has only appeared in six films prior to Rules Don’t Apply. And excepting Bugsy, those films have been, at best, non-distinctive—Dick Tracy, Love Affair, Bulworth; at worst, disasters—Ishtar, Town and Country. That record makes one wonder just how interested Beatty is, at age 79, in making films at this stage in his life. Because Rules Don’t Apply seems to me to be rather uninspired for a film that Beatty has contemplated doing for so long. One can excuse all of the rather excessive use of dramatic license if it adds up to something justifiable on its own. But the best one can say about the film’s meaning is that it shows us how two young people finally see that Howard Hughes is an irresponsible scoundrel who, for all his money, is someone they would be better off without. Which is the same message one can get from, say, the film of The Devil Wears Prada.

As a film, the best one can say is that it is competently made. There was one memorable shot in it. At night, Hughes and Frank are having hamburgers at the Long Beach airport, the camera at a high angle looking down on them. We then reverse the angle and see that they are staring at the colossal Spruce Goose in its hangar. But that’s about it as far as visual creativity and drama go. And I hate to say it, but that lack of creativity extends to Beatty’s performance. Twelve years ago I was not enamored with Leonardo DiCaprio’s performance as Hughes in The Aviator, but at least he tried for the basic outline and design of the man. In Rules Don’t Apply, Hughes does not appear until about twenty minutes into the film. But from the outset, this reviewer was surprised at how superficial Beatty’s acting was. There are several films that survive of Hughes today. Watching those films would be a starting point for any actor. But there seems to me to be very little effort by Beatty to capture any of the vocal inflections or speech patterns of Hughes. And beyond that, there was even less attempt to delineate any of the inner turmoil within the man that finally broke out into dementia in the latter part of the sixties. For me it was a pallid, barely subcutaneous performance from a talented actor who was both vivid and memorable in Bonnie and Clyde, Reds and Bugsy.

As I said, Beatty has been quite liberal in his use of dramatic license in this film. Even in the past, he has had a tendency to romanticize and glamourize his main characters. As Hughes is waiting for his opening phone call, the subtitle appears that this is taking place in 1964. As I said, the actual phone call took place in 1972. But as I walked out of the theater contemplating the mystery of Beatty’s lackluster performance, I wondered if the date of the call had something to do with his acting. For if Beatty had not fictionalized the call or its timing, then he would have had to present Hughes in a much more extreme state of dementia and emaciation. Evidently, as actor-star, he didn’t want to do that. I can’t really blame him for it. Except for someone as dedicated and meticulous as Robert DeNiro, most major American stars don’t like to present themselves as being that distasteful and unattractive.

And that seems to me to be a major problem with the film. As outlined above, there are all sorts of intriguing angles about Hughes’ career that can be explored without using dramatic license. With the grand scope of his life, one could actually make a case that Hughes was a tragic character who, as he himself said, screwed up his life at a rather early age. Rules Don’t Apply avoids virtually all those aspects and turns Hughes into your weird Uncle Willie, the relative who got shoved off into a separate room at Christmas. And his film is really a light romantic comedy.

As I have outlined above, Hughes was a heck of a lot more than that. And the nightmare he lived—touching on the movie business, air travel, the growth of Las Vegas, and the CIA—was a large and fascinating canvas to draw on. Perhaps such a story could only be told through the auspices of a cable channel like HBO, which would give the tale its full airing. Beatty probably should have gone that route. Then he would not have had to reduce this large-scale saga to the status of a fairy tale for adults.

Because Beatty has made some distinguished historical films, many had high hopes for this one. But the result seems to be rather uninspired for a film that he has contemplated doing for so long. The best one can say is that it is competently made, writes Jim DiEugenio.

Because Beatty has made some distinguished historical films, many had high hopes for this one. But the result seems to be rather uninspired for a film that he has contemplated doing for so long. The best one can say is that it is competently made, writes Jim DiEugenio.