|

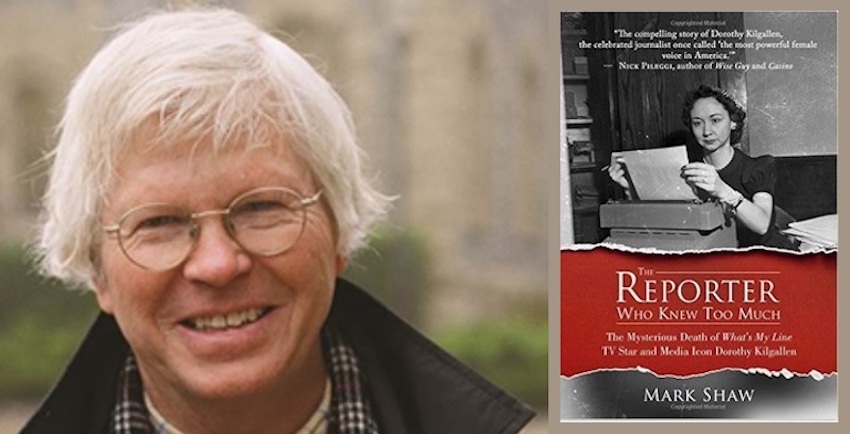

| Dorothy Kilgallen's posthumous book |

Prior to Shaw’s book, there had been three major sources about Kilgallen’s life and (quite) puzzling death. The first was Lee Israel’s biography titled Kilgallen. Published in hardcover in 1979, it went on to be a New York Times bestseller in paperback. As we shall later see, although Israel raised some questions about Kilgallen’s death in regards to the JFK case, she held back on some important details she discovered. In 2007, Sara Jordan wrote a long, fascinating essay for the publication Midwest Today Magazine. Entitled “Who Killed Dorothy Kilgallen?”, Jordan built upon some of Israel’s work, but was much more explicit about certain sources, and much more descriptive about the very odd crime scene. For instance, the autopsy report on Kilgallen says she died of acute ethanol and barbiturate intoxication. But it also says that the circumstances of that intoxication were “undetermined”. Jordan appropriately adds, “for some reason the police never bothered to determine them. They closed the case without talking to crucial witnesses.” (Jordan, p. 22) A year later, in the fall of 2008, prolific author and journalist Paul Alexander had his book on the subject optioned for film rights. The manuscript was entitled Good Night, Dorothy Kilgallen. Reportedly, one focus of Alexander’s volume was how the JFK details Kilgallen wrote about in her upcoming book, Murder One, were cut from the version posthumously published by Random House. Neither Alexander’s book, nor the film, has yet to be produced. Which is a shame, since the available facts would produce an intriguing film.

I

Dorothy Kilgallen was born in Chicago in 1913. She graduated from Erasmus High School in 1930. At Erasmus she had been the associate editor of her high school newspaper. (Shaw, p. 3) Her father, James Kilgallen, was a newspaperman who worked for the Hearst syndicate in Illinois and Indiana. She spent a year in college in New York City. While there, her father got her a reporter tryout with the New York Evening Journal. She dropped out of college, and this became her lifelong career and position.

While at the Evening Journal, she carved out a place for herself on the criminal courts beat. She especially liked reporting on murder trials, the more sensational the better. For example, one case involved a wife killing her husband by placing arsenic in his chocolate pudding. (ibid, p. 6) Another trial she covered was the notorious Anna Antonio murder for hire case, where the wife hired hit men to kill her husband for insurance money. (ibid, p. 7) In 1935, at the age of 22, she covered the most sensational case of the era: the trial of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son. (ibid) Shortly after this, Kilgallen entered a Race Around the World contest. That race generated tremendous publicity since it involved three reporters for major newspapers. In 24 days, she finished second to Bud Ekins. But, more importantly, she wrote a book about this experience that was then made into a movie. (Jordan, p. 17)

|

| The Original "What's My Line?" Panel (1952) |

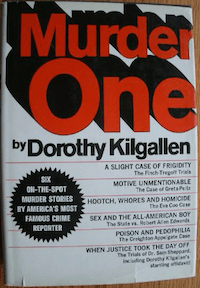

O. O. Corrigan passed away in 1938. For years, he had maintained a very successful column called The Voice of Broadway. Shortly after his death, Kilgallen was given his position. (Lee Israel, Kilgallen, p. 104) In that column she covered politics, crime and the theater scene in New York. In 1940 she married actor/singer and future Broadway producer Richard Kollmar. They had three children, Richard, Kerry and Jill. She became, in 1950, one of the regulars on the game show What’s My Line? The other regular panelists were actress Arlene Francis, and publisher Bennett Cerf; the host was John Daly.

In 1954, Kilgallen covered another sensational legal proceeding. This was the murder trial of Dr. Sam Sheppard. In July of 1954, the doctor and his wife were entertaining guests at their lakefront home in suburban Cleveland. While watching a movie on TV, Sheppard fell asleep. His wife Marilyn escorted the guests out a bit after midnight. (Kilgallen, Murder One, p. 238) Just before dawn, Sheppard called the mayor of the town of Bay Village, the Cleveland suburb where he lived. The mayor and his wife came over. Sheppard was slumped over in the den with a medical kit open on the floor. He appeared to be in shock. He mumbled: “They killed Marilyn.” The couple went up the stairs and saw her bloodied body in the bedroom. (ibid, p. 239) Sheppard said he had been awakened by Marilyn’s screams. He ran upstairs to the bedroom and saw an intruder in the shadows. The assailant knocked him out with a blunt object. When he came to, he heard the intruder downstairs on the porch. He ran down, chased him off the property, and he struggled with him on the lakeshore—where he was bludgeoned unconscious again. (ibid, pp. 239-40)

When she arrived in Cleveland, Kilgallen was struck by both the weakness of the prosecution’s case, and by the powerful bias of the media against Sheppard. But in the face of the latter, the judge failed to sequester the jury. In December, after four days of deliberations, the jury convicted Sheppard of murder. Kilgallen was shocked. In her view, the prosecution had not proven Shepard guilty any more than they had “proved there were pin-headed men on Mars.” (ibid, p. 300)

|

| Sam Sheppard & F. Lee Bailey |

Years later, after Sheppard’s original lawyer, William Corrigan, had passed away, F. Lee Bailey took on his appeal. At a book signing in New York, he had heard Kilgallen speak about her in-chambers interview with the judge in the Sheppard case. He contacted her about this and she gave Bailey a deposition. In that deposition, she revealed that, before the trial began, she was granted an interview with the judge. He asked her what she was doing in Cleveland. She said that she was there to report on the mystery and intrigue of the Sheppard case. The judge replied, “Mystery? It’s an open and shut case.” Kilgallen said she was taken aback by this remark. She told Bailey, “I have talked to many judges in their chambers—they don‘t give me an opinion on a case before it is over.” She continued that the judge then said Sheppard was “guilty as hell. There’s no question about it.” (ibid, pp. 301-02) This deposition was quoted in the final decision of the U. S. Supreme Court which, in 1966, granted Sheppard a new trial.

At the 1966 trial, Sheppard was acquitted. Bailey’s criminologist, Dr. Paul L. Kirk, presented evidence that there was a third type of blood in Marilyn’s bedroom, not the doctor’s or the victim’s. Further, Kirk concluded the blows that killed Marilyn came from a left-handed person. Sheppard was right handed. (ibid, p. 304)

The Sheppard case dragged on for so long, creating so much controversy, making so many headlines, that it reportedly became the basis for the TV series The Fugitive, starring David Janssen. For our purposes, the important thing to recall about it, and the reason I have spent some time on it, is that Kilgallen was correct about the verdict. And further, her role in the case helped set free an innocent man. Although that last act did not occur until after her own death in November of 1965.

II

The first real inquiry into Dorothy Kilgallen’s death was by the late author Lee Israel. This was done for her best-selling biography, titled Kilgallen, a book still worth reading today. Since that book was not published until 1979, this means that neither the NYPD, nor the House Select Committee on Assassinations did any kind of serious review of the case. This is odd since the circumstances surrounding Kilgallen’s demise clearly merited an inquest. But beyond that, and as we will see, there appears to have been an attempt to cover up the true circumstances of her death.

|

| Kilgallen, with Jack Ruby defense attorneys Joe Tonahill (center) & Melvin Belli (right), at the Ruby trial (February 19, 1964) |

Lee Israel did a good job in her book in describing just how much Kilgallen wrote about the failings of the Warren Commission. She also described some of Kilgallen’s extensive contacts with early researcher Mark Lane. It is safe to say that no other widely distributed columnist in America wrote as often, or as pointedly, about the JFK case as Kilgallen did. She flew to Dallas to cover the trial of Jack Ruby in early 1964. While there, she secured two private interviews with the accused. She never divulged what was revealed to her in those interviews. Instead, the notes from these meetings went into her ever expanding JFK assassination file—which more than one person saw since, at times, she actually would carry it around with her. (Israel, p. 401)

From the contacts she attained in covering the Ruby trial, Kilgallen broke two significant JFK stories. First, someone smuggled her the testimony of Jack Ruby before the Commission. After convincing her editors to print the purloined hearing, her paper ran the story over three consecutive days. And they allowed her to append comments and questions to the colloquy. (Israel, p. 389) Her Dallas sources also secured her an early copy of the DPD radio log. With this she pointed out that Police Chief Jesse Curry had misrepresented to the public his real opinion as to what the origin point of the shots were. He had told the public he thought they came from the Texas School Book Depository, but on the log he said they came from the rail yards, behind the picket fence, atop the grassy knoll. (Israel, p. 390)

When documents on Oswald were denied to Ruby’s defense team, again Kilgallen chimed in pungently:

It appears that Washington knows or suspects something about Lee Harvey Oswald that it does not want Dallas and the rest of the world to know or suspect. . . Lee Harvey Oswald has passed on not only to his shuddery reward, but to the mysterious realm of “classified” persons whose whole story is known only to a few government agents.

Why is Oswald being kept in the shadows, as dim a figure as they can make him, while the defense tries to rescue his alleged killer with the help of information from the FBI? Who was Oswald, anyway? (Israel, p. 366)

She also ran a story suggesting that there were witnesses who saw Oswald inside Ruby’s Carousel Club. (Shaw, pp. 66, 67) Based upon that, she once said, “I don’t see why Dallas should feel guilty for what one man, or even 3 or 5 in a conspiracy have done.” (Shaw, p. 68)

When the Ruby case was decided and he was found the sole guilty party—a verdict that would later be reconsidered—Kilgallen, again, wrote about it quite resonantly:

The point to be remembered in this historic case in that the whole truth has not been told. Neither the state of Texas nor the defense put all of its evidence before the jury. Perhaps it was not necessary, but it would have been desirable from the viewpoint of all the American people. (Israel, p. 372)

In fact, as Israel wrote, Kilgallen actually became a funnel for men like Lane and Dallas reporter Thayer Waldo to run information through, in order for it to garner a wider audience. (Israel, p. 373)

She went even further. Kilgallen ran experiments with her husband holding a broomstick to replicate the alleged sighting by Warren Commission witness Howard Brennan. Brennan was the Commission’s chief witness as to a description of Oswald as the sixth floor assassin. She stood approximately where Brennan stood in front of her five-story townhouse. And she told her husband to go ahead and kneel, as the Warren Commission said Oswald was behind a box. She came to the conclusion that there was “no way in the world that such a description could have been accurately determined by Brennan.” (p. 391) She further came to the conclusion that there was a real question as to the type of weapon that was found in the building, a Mannlicher-Carcano or a Mauser. She was also tipped off as to the ignored testimony of witness Acquila Clemmons. Contrary to the Warren Report, Clemmons claimed to have seen two men involved in the murder of Officer J.D. Tippit, not one, and neither resembled Oswald. These stories were mentioned in her newspaper column in September of 1964. (Israel, p. 395)

The FBI visited her to find out how she got Ruby’s testimony before the Warren Commission. She made them tea but told the two agents that she could never reveal how she got that exhibit or who gave it to her. And when the Warren Report was released in September of 1964, Kilgallen made it fairly evident how she felt about it:

I would be inclined to believe that the Federal Bureau of Investigation might have been more profitably employed in probing the facts of the case rather than how I got them …. At any rate, the whole thing smells a bit fishy. It’s a mite too simple that a chap kills the President of the United States, escapes from that bother, kills a policeman, eventually is apprehended in a movie theater under circumstances that defy every law of police procedure, and subsequently is murdered under extraordinary circumstances. (Israel, p. 396)

What she said and did in private on the JFK case was even more extreme than her public actions. After her experience with the FBI she concluded that Hoover had tapped her home phone line. She told Lane that, “Intelligence agencies will be watching us. We’ll have to be very careful.” She decided to communicate with Lane via pay phones and even then by using code names. She then added, “They’ve killed the president, the government is not prepared to tell us the truth, and I’m going to do everything in my power to find out what really happened.” (Israel, pp. 392-93) She told her friend Marlin Swing, a CBS TV producer and colleague of Walter Cronkite, “This has to be a conspiracy.” (ibid, p. 396) To attorney and talent manager Morton Farber, she characterized the Warren Commission Report as “laughable.” She then added, “I’m going to break the real story and have the biggest scoop of the century.” (Israel, p. 397) She made similar statements to another TV producer Bob Bach, and another talent manager, Bill Franklin. (Israel, p. 396) All this, of course, was contra what almost all of her professional colleagues were involved with at the time: namely praising and venerating the fraud of the Warren Report. For instance, in June of 1965, Kilgallen was invited to do an ABC news show called Nightlife with Les Crane. Since Bach had helped arrange the appearance she thought she would be speaking about the Warren Report, so she brought parts of her JFK file with her. But she was informed by one of the show’s producers, Nick Vanoff, that they did no want her to address that subject. He told her it was “too controversial”. (Israel, p. 401)

Between the time of the release of the Warren Report—September of 1964—and her passing—November of 1965—she was in the process of taking and planning flights to both Dallas and New Orleans. (For the former, see Israel, p. 402; for the latter, see Jordan, p. 20) These do not appear to be job related. They appear to be for the purpose of advancing her own inquiry into Kennedy’s assassination. For instance, she told What’s My Line? makeup artist Carmen Gebbia that she was excited about an upcoming trip to New Orleans to meet a source she did not know. She said it was all cloak and daggerish. And she concluded that, “If it’s the last thing I do, I’m going to break this case.” (Jordan, p. 20)

|

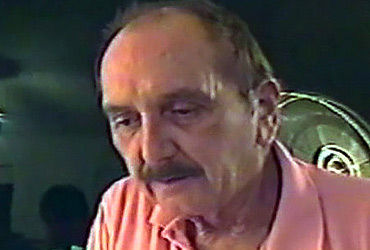

| Marc Sinclaire |

Marc Sinclaire worked for Kilgallen as her major hairdresser. Many years after her death he revealed that he went to New Orleans with her in October of 1965. Sinclaire went down on a separate plane and stayed in a different hotel. They had dinner together the night he arrived. The next morning he was preparing to go to her place to work on her hair. She called him and said that was cancelled: she had purchased a ticket for him and he was to return to New York. Further, he was not to tell anyone he had been there with her. Her second hairdresser, Charles Simpson, said she used to tell him things about her work, but now things were different. She proclaimed “I used to share things with you … but after I have found out now what I know, if the wrong people knew what I know, it would cost me my life.” (ibid)

III

Two of the problems with the circumstances of Kilgallen’s death are that first, the cause was misreported by her own newspaper, and second, no one can pinpoint exactly when her body was first discovered. Using her father as a source, the Journal American reported that Dorothy Kilgallen had died of an apparent heart attack. (Israel, p. 410) As we shall see, that was not the case. But even more puzzling, there is a real mystery as to when the corpse was first discovered.

The official police record states that the body was found between noon and 1 PM by Marie Eichler, Kilgallen’s personal maid. (Israel, p. 416) But Israel talked to an anonymous source who was a tutor to the Kilgallen children and was there on the morning of November 8, 1965. That source told Israel that the body was found much earlier, before ten o’clock. Sara Jordan later revealed the tutor was Ibne Hassan. Hassan’s information turned out to be correct. From the information on hand today, the first known person to discover Kilgallen’s body was Sinclaire. And his (unofficial) testimony has powerful relevance. He said that he was stunned when he found Kilgallen sleeping on the third floor. Because she always slept on the fifth floor. He found her sitting up in bed with the covers pulled up. He walked over to her, touched her, and knew she was dead. In addition to being on the wrong floor, she was wearing clothes that she simply did not wear when she went to bed. Further, she still had on her make up, false eyelashes, earrings, and her hairpiece. (Jordan, p. 21)

A book was laid out on the bed. It was Robert Ruark’s recent volume The Honey Badger. Yet, according to more than one witness, Kilgallen had finished reading this book several weeks—perhaps months—prior. Also, she needed glasses to read; Sinclaire said there were none present. The room air conditioner was running, yet it was cold outside. Plus the reading lamp was still on. Sinclaire added, her body was neatly positioned in the middle of the bed, beyond the reach of the nightstand. (ibid)

The questions raised by Sinclaire’s description are both obvious and myriad. The setting suggests that Kilgallen’s body was positioned both on a floor she did not sleep on and in a way that was completely artificial. In other words, it was posed. If this was done, it was performed by someone not familiar with her living routine and in a hurry to leave, probably for fear of awakening someone. But this is not all there is to it. Sinclaire said there was also a drink on the nightstand. (As we shall see, there more likely were two glasses there.) When Sinclaire called for the butler, he came running up the stairs, very flustered. Sinclaire then left through the front door. He said that there was a police car there, with two officers inside. They made no attempt to detain him. That morning, a movie magazine editor named Mary Branum received a phone call. The voice said, “Dorothy Kilgallen has been murdered”, and hung up. (ibid)

|

| Charles Simpson |

When Sinclaire got home he called his friend and colleague Charles Simpson. He told him that their client was dead. He then added, “And when I tell you the bed she was in and how I found her, you’re going to know she was murdered.” Simpson later said in an interview, “And I knew. The whole thing was just abnormal. The woman didn’t sleep in that bed, much less the room. It wasn’t her bed.” (ibid. These video taped interviews were done by researcher Kathryn Fauble. The Jordan article owed much to her research, and so does Shaw. See Shaw, p. 113)

From Sinclaire’s description, there seems to have been a prior awareness of Kilgallen’s passing: e.g., the police car in front of the door. But as of today, Sinclaire is the best testimony as to when the body was actually found. About three hours later, two doctors arrived at the townhouse: James Luke and Saul Heller. The latter pronounced her dead. But the former did the medical examination, which as we shall see, was incomplete.

About a week after her death, Luke determined that she was killed by “acute barbiturate and alcohol intoxication, circumstances undetermined.” (ibid, p. 22) Roughly speaking, this means she died of an overdose, but the examiners could not determine how the drugs were delivered. Usually, the examiner will write if the victim was killed by accident, suicide or homicide. That was not done in this case. The main reason it was not done is because there was no investigation of the crime scene, or of any witnesses who saw and had talked to her in the previous 24-48 hours. For example, phone calls were not traced, her home was not searched for drug containers, and there was no investigation as to how she arrived home that evening or if anyone was with her.

Lee Israel was shocked when she discovered this fact. She was looking through the Kilgallen police file for reports labeled DD 5 and DD 15. The former is a supplementary complaint report that records activities pursuant to a complaint. The latter is a request to the Medical Examiner for a Cause of Death notice. Israel said that, although the investigating detective said he saw this, it was missing from the file. (p. 428) Therefore, there appears to have been no investigation done to determine how the drugs were administered. This was so bewildering to Israel that she wrote that there may have been another, unofficial channel, of communication between the police department and the medical examiner’s office on the Kilgallen case.

There does seem to be cause for such speculation. In her book, Israel mentioned another anonymous source from the toxicology department of the medical examiner’s office. (Israel, pp. 440-41) This man was a chemist under Charles Umbarger, director of toxicology at the NYC Medical Examiner’s Office. This source met with Israel personally and told her that Umbarger believed that Kilgallen had been murdered. Umbarger had evidence that would indicate this was the case but he kept it from the pathology department as part of the factionalism in the office. The idea was to retain this secret evidence in reserve over chief Medical Examiner Milton Halpern and Luke. Jordan discovered this secret source was a man named John Broich. (Jordan, p. 22) Broich told Jordan, as he told Israel, that he did new tests on the glasses, and tissue samples, both of which Umbarger had retained. He found traces of Nembutal on one of the glasses. The new tests discovered traces of Seconal, Nembutal and Tuilan in her brain.

This was an important discovery, for more than one reason. First, the police could not find any evidence of prescriptions for the last two drugs by Kilgallen. Her doctor only prescribed Seconal. Second, no doctor would prescribe all three to one patient at one time since the mix could very well be lethal. (Shaw, p. 116) Third, the prescription Kilgallen had for Seconal had run its course at the time of her death. Umbarger, of course, knew this. When Broich reported back to him about his new chemical discoveries, Umbarger had an unforgettable reaction. He grinned at his assistant, and then said the following: “Keep it under your hat. It was big.” (Jordan, p. 22)

IV

As we have seen, neither the New York Police Department nor the medical examiner’s office was forthcoming or professional in the Kilgallen case. The House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) only performed a very cursory look at her death. But it appears it was the HSCA that got her autopsy report into the National Archives. (Shaw, p. 277) That cursory look seems odd for the simple reason that the HSCA’s chief pathologist, Dr. Michael Baden, was working in the Medical Examiner’s office at the time of Kilgallen’s passing. In fact, Baden’s name is listed as an observer for Luke’s autopsy report. (Shaw p. 102) Baden was also a source for Israel’s book. In 1978, while the HSCA was ongoing, he told Israel that, from what he could see, the evidence would indicate that Kilgallen had fifteen or twenty 100 mg capsules of Seconal in her system. (Israel, p. 413) Why Mark Shaw did not make more of this point in his book eludes this reviewer. Because Baden’s opinion would seem to be incorrect, for the simple reason that, as stated above, Kilgallen likely would not have had that many Seconals left in her prescription at the time of her death. But a fewer number of Seconals, mixed with the two other drugs, would very likely have produced the fatal result.

Because of the (screamingly) suspicious circumstances of her death, it does not at all seem logical to consider either of the other alternatives—that it was accidental, or she took her own life. How could she accidentally end up in the wrong bed on the wrong floor with the covers pulled up? As per the second option, as stated above, there seems to not have been enough left of her Seconal prescription for her to take her own life. According to her doctor, Kilgallen was prescribed 50 pills per month. There are two reports, one from the police, one from her doctor, but the estimates are that she took between 2-4 pills per night. (Israel, p. 425) Since the prescription was last filled on October 8th, how could there possibly be enough pills available for her to plan her death? The indications seem to suggest this was a homicide.

|

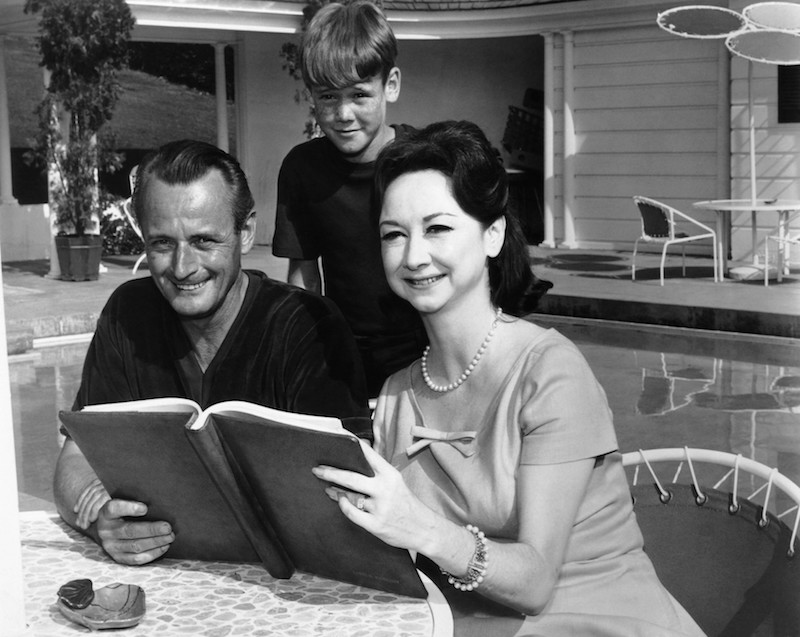

| Kilgallen, Richard Kollmar & their son, Kerry (1964) |

If that were the case—and Israel, Jordan, and Shaw certainly seem to agree it is the strongest alternative—then who was responsible? One possible suspect is her husband Richard Kollmar. As Israel and Shaw outline, neither spouse was faithful to the other at this stage of the marriage. Richard was involved in several one-night stands, and Dorothy had a love affair with singer Johnny Ray, which had concluded at around the time of Kennedy’s assassination.

Further, Richard was not doing nearly as well financially as Dorothy was. Israel had direct access to their accountant, Anne Hamilton. And from that interview, it appears that Shaw overstates their wealth significantly. (See Israel, especially p. 356) But there can be little or no doubt that at the time of her death, Kilgallen was the major breadwinner in the family. Therefore, in case of her death, Richard would be in position to inherit a significant amount of money in cash and property, well over a million dollars today. Further, and another point I could not find in Shaw’s book, Richard had his own access to Tuinal. (Israel, p. 438)

But still, there are serious problems with holding Richard as the prime suspect. First, if such were the case, then why would there be such an almost appallingly negligent investigation? Cases of spouses killing their partners must have appeared every week in a city as large as New York. And, if so, how would Richard have the influence to cause such a large system failure—one that took place in the police department, the DA’s chambers, and in the office of the medical examiner? Secondly, no one who knew Kollmar thought he was capable of doing such a thing. Both Israel and Shaw agree on this point. But third, if Kollmar had planned the whole thing, how could he possibly have left as many holes in his plot as he did— many of them wide enough to drive the proverbial tractor through? Could he really have not known where his own wife slept? What she wore when she retired? What book she was reading? That when she read, she wore glasses? And so on and so forth. The case does not appear to be an inside job. Because if Marc Sinclaire had not left that morning, he could have detonated it in about two minutes.

|

| Ron Pataky & Kilgallen |

Both Israel and Jordan seemed to center their suspicions on a man that the former referred to as the Out of Towner. Israel referred to him by that rubric because he lived and worked in Columbus, Ohio. His real name is Ron Pataky. In her Midwest Review essay, Sara Jordan was explicit about his name and printed a photo of him standing next to Kilgallen. There are several reasons why Ron Pataky’s presence creates suspicion in this case. One has to do with the closeness of his relationship with Kilgallen at the time. After she and Johnnie Ray decided to break up, it appears that Pataky became Kilgallen’s romantic interest. They called each other frequently, saw each other on occasion, and wrote letters and notes to each other. A very odd thing happened in late October on the set of What’s My Line? Before the show began taping, an announcement came on the public intercom. The voice said, “The keys to Ron Pataky’s room are waiting at the front desk of the Regency Hotel.” Quite naturally, this shook Dorothy up. Why didn’t someone just bring her a note? Pataky denied being in New York at that time. If so, was someone trying to tell the reporter that they knew something about her private life? (Jordan, p. 20) On the weekend of her death, Kilgallen had an hour-long call with Sinclaire. During this call, she said her life had been threatened (she later said she might have to purchase a gun). Sinclaire told her that the only new person in her life was Pataky. And she had shared her interest in, and information about, the JFK case with him. He suggested that she confront him with those facts. Two days later, Kilgallen was dead. (Shaw, p. 242)

Both Israel and Shaw discuss interviews they had with Pataky. In more than one place it appears that the subject is being less than candid. For instance, he says that he was never at Kilgallen’s townhouse. But he says that he knew Kilgallen drank and popped pills. When asked how he knew that, he says he saw the pills in a medicine cabinet. Unless Dorothy carried a medicine cabinet with her, how did he know about it if he was never in her home? Pataky also said in 2014 that the New York police talked to him about Dorothy’s death based upon a note they discovered at the home. Yet there is no evidence of any such interview or note in any police file. (Shaw, pp. 239-40) Another example would be one of his alibi witnesses. Pataky has always maintained that he was in Columbus when he got the news of Dorothy Kilgallen’s death. He said fashion editor Jane Horrocks read the notice off the news wire to him. But researcher Kathryn Fauble later talked to Horrocks. She remembered Pataky vividly since they shared an office at the Columbus Citizen-Journal. She also recalled him getting calls from Kilgallen there. But she added on the day the news broke about Kilgallen’s death she wasn’t in the office, she was on assignment in California. (Shaw, p. 237)

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of any interview with Pataky was the one Israel did with him about Kilgallen’s final hours. Sara Jordan, Israel and Shaw have attempted to reconstruct what Kilgallen did the evening before she was discovered dead by Sinclaire. After taping What’s My Line?, she and producer Bob Bach went to the restaurant/bar P. J. Clarke’s for a drink. (Jordan, p. 21) Both Bach and Sinclaire have stated that Kilgallen separately told them she was to meet with someone at the Regency Hotel later that evening. Therefore, after she left P. J. Clarke’s, she arrived at the Regency, which is about six blocks from her home. In a videotaped interview with an associate of Kathryn Fauble, it was revealed that Kilgallen was seen in the corner of the cocktail lounge by a woman named Katherine Stone. Stone had been a contestant on the show that night. (ibid) Press agent Harvey Daniels also recalled seeing Kilgallen with a man at the Regency that night. So did piano player Kurt Maier. (ibid) She left the Regency at about 2 AM. According to Israel, when the news of her death broke, several people working at the Regency discussed her presence there the night before. (Israel, p. 432)

Pataky has always denied he was with her that evening. He has always denied he was in New York that night. The most he would say is that she called him that evening. But Pataky firmly declared that he was in Columbus that evening, not in New York. Israel had taped her call with him. She turned it over to former CIA officer George O’toole. O’toole was one of the leading Agency analysts for the Psychological Stress Evaluator, commonly known as the PSE. This device measures stress in the voice in response to questioning. That measurement may reveal the subject is lying about a sensitive point. O’toole wrote an interesting book on the subject in relation to the JFK case, The Assassination Tapes. In that book he explains in detail how the device works and its reputation for accuracy. An absence of stress in the voice would indicate that the subject is telling the truth. If the stress is high, it may reveal tension due to deception. When O’toole analyzed the part of the conversation in which Pataky denied being in New York that night, he wrote that the PSE hit level F and G gradients. These are the highest levels of stress the machine will measure. When Pataky discusses how he actually found out about Kilgallen’s death, again the machine hit the F level. (Israel, p. 435)

Pataky had designs to be a songwriter. He had confided in Kilgallen about this. The verses of a song are, in many ways, like a poem. So years later, Pataky posted some of his poems online. Both Shaw and Jordan found them interesting. First there is one called “Never Trust a Stiff at a Typewriter”. It reads as follows:

There’s a way to quench a gossip’s stench

That never fails

One cannot write if zippered “tight”

Somebody who’s dead could “tell no tales.”

As to its suggestiveness to the topic, this needs no comment. The second Pataky poem is called “Vodka Roulette Seen As Relief Possibility”.

While I’m spilling my guts

She’s driving me nuts

Please fetch us two drinks

On the run.

Just skip all the nois’n

Make one of them poison

And don’t even tell me

Which one!

Shaw goes on for four paragraphs on this poem. But again, its suggestiveness needs little explication in relation to the subject at hand.

Let us close the discussion of Pataky with another piece of information allegedly supplied by Israel, but which today is in dispute. John Simkin used to own and operate the JFK Assassination Debate forum at Spartacus Educational web site. He had an abiding interest in the Kilgallen case. In a discussion at Simkin’s site in 2005, he enlisted Israel to participate. During this discussion it was revealed that in 1993 a college student in Virginia did what Israel did not do in her book. He actually revealed Pataky’s name. And he further wrote that the management of the Regency Hotel had forbidden its employees to discuss Kilgallen’s presence there that night. But even more interesting, Israel said that she found out that Pataky dropped out of Stanford in 1951 and later enrolled in the School of the Americas in Panama. This, of course, is the infamous CIA training ground for many Central American security forces who were later involved in various kidnappings and assassinations in the fifties and sixties. In the Midwest Today article by Sara Jordan, Israel denied she made this statement. (But Jordan found out that Pataky did drop out of Stanford after one year. Jordan, p. 23) Yet to this day, that statement exists in black and white on that site. It’s kind of a reach to say Simkin invented it. And we know that Israel was sensitive about what she wrote about Pataky, or else she would have named him in her book.

V

After writing all the above I would like to say that Mark Shaw wrote an admirable and definitive volume about Kilgallen and her death. Unfortunately, I cannot do so. One reason is obvious from my references. A lot of the information in Shaw’s book can be found in either Israel’s tome or the Sara Jordan essay in Midwest Today. The interviews with Sinclaire and Simpson were done by the indefatigable Kathryn Fauble. Shaw does a nice job in reporting on the autopsy. And his interviews with Pataky are informative. But some of the book seems padded, consisting of chapters about four pages long. (See Chapter 34) Sometimes, the author repeats information, as with Sinclaire finding the body. And like writers who partake in biography, Shaw tends to exaggerate the achievements of his subject.

This last is done in two ways. He tends to exaggerate Kilgallen’s stature as a journalist. For example, he calls her the first true female media icon. (p. 294) Did the author forget about Dorothy Thompson? Or Adela Rogers St. Johns? They certainly ranked with Kilgallen in popularity and as role models. And Thompson left behind a body of work at least equal in stature to Kilgallen’s and, by any rational measure, exceeding it. Shaw also quotes Ernest Hemingway as calling Kilgallen, “One of the greatest women writers in the world”. I could not find a source for this quote. But on what grounds would such an expansive judgment hold water? And why would Shaw want to use it? Kilgallen wrote two books. She actually co-wrote them. The first was about her trip around the world, which she wrote with Herb Shapiro in 1936. Murder One was published posthumously by an editor based on her notes. This plus her voluminous columns are the sum total of her literary output. Does that compare with the achievements of say Isak Dinesen, Katherine Anne Porter or Rebecca West?

The second way Shaw inflates his subject is by discussing what her impact would have been on the JFK case. This is completely unwarranted and amounts to nothing but pure speculation. For the simple reason that no one is ever going to know what Kilgallen discovered, or what her talks with Ruby were about. Therefore, the database from which to measure her achievement is simply non-existent. But, to put it mildly, this does not hinder Shaw. In a perverse sort of way, it enables him. Near the end of the book he writes that, “If Kilgallen had lived … the course of history would have been altered.” (Shaw, p. 288) Since, as stated above, there is no database to support that statement with, this reviewer is puzzled as to how Shaw arrived at this outsized conclusion.

Which leads to two other related problems with Shaw’s book. First, the author’s footnotes would not pass muster in a sophomore English class. Time after time he refers to newspapers without adding a date to them. Time after time, he refers to books without supplying a page number. This, of course, makes it difficult to crosscheck his work. Secondly, he repeatedly refers to the mystery of how Dorothy’s JFK file disappeared after her death. Yet in Sara Jordan’s essay, she quotes a conversation between the Bachs and Richard Kollmar after Dorothy’s death. They asked him, “Dick, what was all that stuff in the folder Dorothy carried around with her about the assassination?” Richard replied, “Robert, I’m afraid that will have to go to the grave with me.” (Jordan, p. 22) What this means is anyone’s guess. But it could mean that he somehow recovered it and destroyed it.

One of the worst aspects of The Reporter who Knew Too Much is how Shaw’s inflation is somewhat self-serving. For instance, when I saw the author speak at last year’s JFK Lancer conference he made a couple of rather odd statements. He said that since Kilgallen had gone to New Orleans with Sinclaire, this meant that she was investigating Carlos Marcello for the JFK case. Again, for reasons stated above, there is no factual way that Shaw could know such a thing. But further, how does New Orleans automatically deduce Marcello? New Orleans is honeycombed with a multitude of leads on the JFK case. Lee Oswald spent about six months there from the spring to the fall of 1963, less than two months before he was killed. To say that what he did there would automatically lead to Marcello betrays an agenda that is not really dealing with Kilgallen.

That agenda traces back to a book Shaw wrote in 2013. It was called The Poison Patriarch. This reviewer did not critique it since it was simply not worth discussing. But Shaw synopsizes it here in order to attribute what Kilgallen was going to do if she had lived. Shaw’s previous work is a feat of Procrustean carpentry that ranks with the likes of Peter Janney and Philip Nelson. And like those authors, Shaw used an array of dubious witnesses to achieve his feat of alchemy. In short, he said that JFK was killed because Joseph Kennedy insisted on Bobby Kennedy as Attorney General. The father had underworld ties, should have known that RFK was going to do battle with the Mafia, and this caused a revenge tragedy to be performed. To scaffold this utterly bizarre thesis, Shaw trotted out a virtual menagerie of dubious witnesses like Tina Sinatra, Frank Ragano, Toni Giancana, Sy Hersh and Chuck Giancana. The book was a recycling and revision of Chuck Giancana’s science fiction fable Double Cross. (See pages 179-180 of the present book.)

Well, in The Reporter Who Knew Too Much, Shaw pens his imaginary conclusion to Kilgallen’s investigation. He writes that after she made her second trip to New Orleans, the reporter produced a series of articles connecting Oswald, Ruby and Marcello. This series triggered a grand jury inquiry. This culminated in indictments of Marcello for the murders of both Kennedy and Oswald. But Kilgallen’s evidence went further. It also managed to indict J. Edgar Hoover for obstruction of justice, and he resigned his position. As a result, Kilgallen’s disclosures changed the way that the JFK case was discussed in history books.

I wish I could say that what I just described is an exaggeration or parody of what Shaw wrote in his book. Unfortunately it is not any such thing. If the reader turns to page 289, he can read it for himself. To say that such writing is a fantasy really does not do it justice. The idea that Kilgallen was going to take on the entire power structure of the USA and overturn it with a series of newspaper columns is almost too ridiculous to consider. As many authors have proven, the JFK cover-up was interwoven throughout the entire structure of the American government at that time: the White House, the Justice Department, the Secret Service, the CIA, and the FBI. The Power Elite was involved in it through organs like the New York Times, CBS, and Life magazine. The idea that Kilgallen was going to upend this whole colossal structure is a bit ludicrous. As mentioned, she could not even discus the JFK case on Les Crane’s talk show. Which was a harbinger of what was going to happen to Jim Garrison in 1968 on The Tonight Show. I hate to inform Mark Shaw, but the Sam Sheppard murder case is not the Kennedy assassination.

If Shaw would have restrained himself, or if he had an editor who would have pointed out the problems with his design, then this would have been a good and valuable book. It would have been really about Dorothy Kilgallen: who she really was, what we know and do not know about her death. But as shown above, such was not the case. Thus I would actually recommend to the interested party Sara Jordan’s informative and objective essay instead.

The recommended essay can be found here: