"What do you expect from a pig but a grunt?"

– Kevin Costner as Jim Garrison, JFK

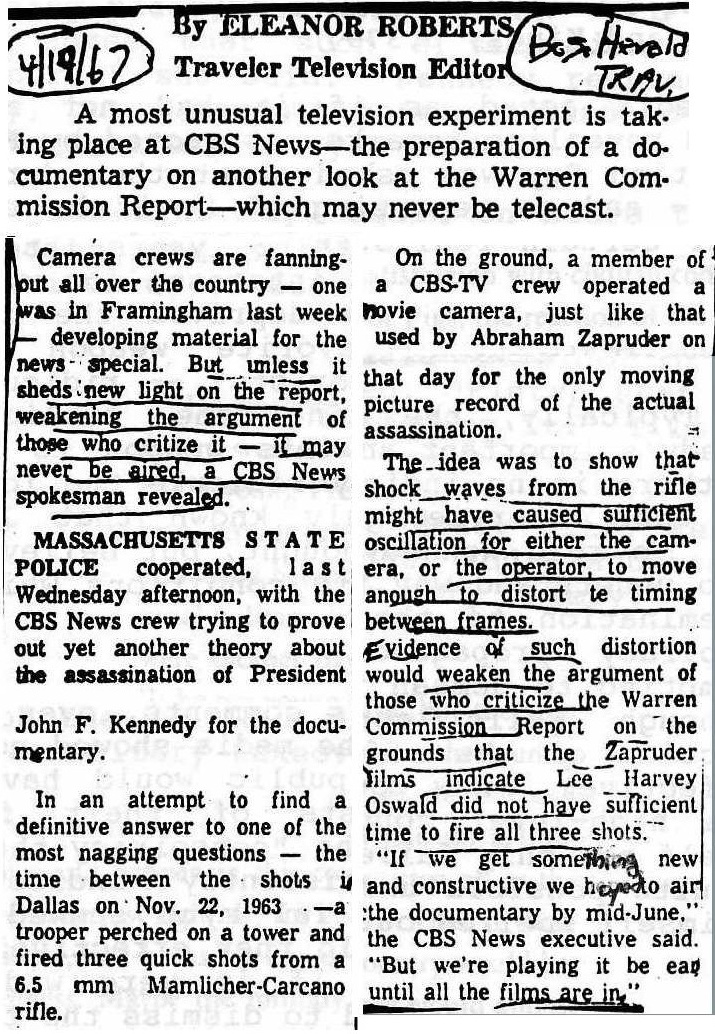

In early February 1967, Warren Commission critic Ray Marcus received a letter from Robert Richter of CBS News. The news organization was thinking of producing a new program on the Warren Report, Richter said, and was contacting some of its critics. One of them, Vincent Salandria, had given Richter a copy of The Bastard Bullet and described some of Marcus's other work. Perhaps Marcus would be willing to give CBS a hand.

Marcus wrote back on February 14: "I shall be happy to assist as best I can." He described his Zapruder film analysis and his conclusions on the assassination shot sequence, and some of his photographic work, including the #5 man detail of the Moorman photograph, which he believed revealed a gunman on the grassy knoll.

A few months later Marcus nearly changed his mind. He was in Boston attending to some business interests when he happened to see an article in The Boston Herald-Traveler by the paper's television editor, Eleanor Roberts. The article's first sentence told most of the story. "A most unusual television experiment is taking place at CBS News—the preparation of a documentary on another look at the Warren Commission Report—which may never be telecast." Unless CBS could develop new information that weakened the arguments of the Commission's critics, Roberts wrote, the project might be shelved.

Immediately, Marcus telephoned Roberts. She would not tell him the source of her story, but did say it was a CBS executive who had been a reliable contact in the past.

A few weeks later Marcus heard again from Bob Richter. The CBS program was in development and he wanted to discuss Marcus's work with him. But Marcus said no, he had changed his mind; he had seen the Roberts article, and it was plain that CBS was not approaching the subject impartially.

But Richter had a good comeback. "Some of us here are trying to do an honest job," he said, "and if those of you who have important information don't cooperate with us, you're just guaranteeing that the other side wins." Richter seemed sincere and his reasoning sound. Marcus agreed to meet with him.

The two men met several times and Marcus outlined the work that he had done. Richter was impressed with the Moorman #5 man detail (below right), discovered by David Lifton in 1965, which Marcus and Lifton both believed revealed a Dealey Plaza gunman. Richter agreed that the murky image was almost certainly a man. He saw a series of ever-larger blow-ups of the picture, which Marcus had placed in a special portfolio. Richter arranged to have duplicates made of the entire set, and said he would show them to his superior at CBS, Leslie Midgley, the producer of the program.

Midgley, it turned out, said he could not see anything resembling a man in any of the pictures when Richter showed them to him. But he agreed to meet with Marcus to go over the portfolio one more time. They met, along with Richter, in Midgley's office. Included in the portfolio was a detail from a photograph of civil rights activist James Meredith moments after he was shot—a photo which revealed, unambiguously, his assailant in the shrubbery along the side of the road. Marcus had included an enlargement of the gunman for purposes of comparison to the #5 man detail, since the lighting and the figure obscured among leaves—this one known to be a man—were similar in appearance. Flipping through the series of #5 man enlargements, Midgley kept repeating that he couldn't see anything that looked human. Then he came to an especially clear photo, and he said, "Yes, that's the man who shot Meredith."

Marcus and Richter immediately glanced at one another, in what Marcus took to be obvious and mutual understanding of what had just happened. Midgley was looking not at the photo of the Meredith gunman, but of the clearest enlargement of the Moorman #5 man detail, which he had previously looked at but dismissed.

Midgley understood what happened, too. He visibly reddened but did not acknowledge the error. Marcus must have felt completely vindicated, for this was an absolute, if tacit, admission: in order for Midgley to wrongly identify the #5 man detail as "the man who shot Meredith," he first had to be able to see #5 man in the picture.

Marcus politely reminded Midgley he was looking at #5 man. The meeting ended shortly after this, without further discussion of what had just happened.

After the incident in Les Midgley's office, Marcus had met again with Richter and stayed in touch with him by telephone. By June, the broadcast date was drawing near, and the CBS project had developed into a four-part special. On June 19 Marcus wrote Midgley an eleven page letter describing, in great detail, the incident in Midgley's office, and calling the mis-identification "a very understandable error. But one which would have been impossible for you to make had you not promptly recognized the #5 image as a human figure, despite your earlier denials that you saw anything in the pictures that looked like a man." With its vast resources, both technical and financial, CBS was obviously capable of presenting the #5 man image clearly and objectively. "Need it be stated," Marcus told Midgley, "that if CBS fails to do so—especially considering your positive reaction to #5 man—that fact in and of itself will constitute powerful evidence that the entire CBS effort was designed to be what I fear it to be: a high-level whitewash of the Warren Commission findings?"

The next morning Marcus mailed the letter to Midgley and enclosed additional copies of #2 and #5 man and other photographs. That same day he telephoned Bob Richter in New York. He wanted Richter to confirm, in writing, the mis-identification of the #5 image that had taken place in Midgley's office, which Richter agreed to do. Then Richter, while cautioning that Marcus would probably be unhappy with the overall content of the four programs, added that some of the Moorman details might make it into the final edit of the show. Richter described one of images but Marcus said it wasn't the best one to use. Which one was? Richter asked. The most advantageous one to show, Marcus replied, would be the clearest one of the bunch—the one Richter's boss, Les Midgley, had mistaken for the man who shot Meredith.

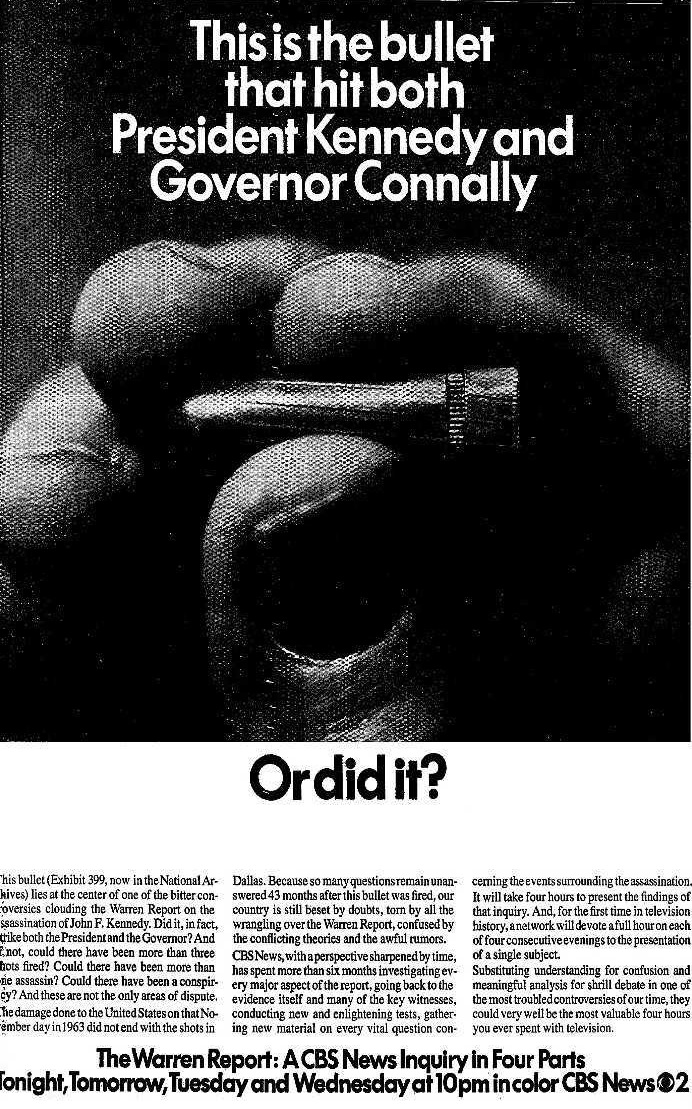

That same evening, the CBS television network broadcast the first of its four-part CBS News Inquiry: The Warren Report. CBS was touting the documentary as "the most valuable four hours" its viewers might ever spend in front of their TV sets. It was anchored by Walter Cronkite, a broadcasting legend already considered the Dean of American television newsmen. Cronkite said later it would have been "the crowning moment of an entire career—of an entire lifetime—to find that Oswald had not acted alone, to uncover a conspiracy that took the life of John F. Kennedy." But, he continued, "We could not."

Each segment of the CBS News Inquiry posed a series of questions and answered them with an unbiased evaluation of the evidence. That, at any rate, was the appearance. The actual content of the four programs left many wondering whether CBS had really taken a disinterested approach to the subject. The Boston Herald Traveler article Ray Marcus had seen, stating that the CBS documentary might really be aimed at "weakening the arguments of those who criticize" the Warren Report, may have been accurate, after all.

Mark Lane also had a stake in the program. "I decided to watch the CBS effort very closely," he said later. Like Ray Marcus, Lane had met with Bob Richter in the months preceding the broadcast, and had also been interviewed for the documentary. After watching the series he concluded that the programs were highly deceptive. "What had evidently been the original approach—to present the evidence and permit the viewer to draw his own conclusions—bore no resemblance to the final concept."

In 1964, Thomas G. Buchanan observed that the facts of the assassination as they were initially reported in the media changed several times, but the conclusion of Oswald's lone guilt never did. "If, as a statistician, I were solving problems with the aid of a machine and I discovered that, however the components of my problem were altered, the machine would always give me the same answer, I should be inclined to think that the machine was broken."

CBS was such a machine. It altered its components with firearms and ballistics tests that improved on the original FBI tests; with new analyses of the Zapruder film; and with new interviews with witnesses to the events of November 1963. But its answer was the same one it had always reported, the same one delivered by the Warren Commission: Lee Oswald, for reasons not entirely fathomable, had murdered President Kennedy without direction or help from anyone.

To answer the questions it posed, CBS used a number of experts. One of them was Lawrence Schiller. Schiller was the photographer and journalist who had once acted as Jack Ruby's business agent, and had played a role in developing research that became an anti-critic triple threat: an article in a World Tribune Journal supplemental magazine, a record album called The Controversy, and a book called The Scavengers and Critics of the Warren Report. CBS used Schiller to refute allegations that a photograph of Lee Harvey Oswald brandishing the alleged assassination rifle was a forgery.

Schiller, Walter Cronkite said, had studied both the original photograph and its negative. Appearing on-camera, Schiller said that the critics "say that the disparity of shadows, a straight nose shadow from the nose, and an angle body shadow proves without a doubt that [Oswald's] head was superimposed on this body." But Schiller said he had gone to the precise location in Dallas where the original was taken, and on the same date, at the same hour, had taken a photograph of his own. This picture, he said, perfectly reproduced the controversial shadows, indicating the Oswald picture was genuine.

Mark Lane was not able to respond to Lawrence Schiller on the CBS program. But he later said that the negative for the photograph was never recovered by the authorities, suggesting the photograph was not genuine. Lane wrote: "It is interesting to fathom the CBS concept of the life of the average American if it imagined that watching Jack Ruby's business agent after he studied a nonexistent negative might constitute 'the most valuable' time spent watching television."

On the second installment of the CBS documentary, Dr. James J. Humes, the Navy doctor who had been in charge of the President's autopsy and had burned his autopsy notes, was interviewed. Asked about the discrepancy between the schematic drawings that placed an entry wound at the base of the neck, and the autopsy "face sheet" that indicated this wound was really lower down on the back, Humes said that the face sheet was "never meant to be accurate or precisely to scale." The exact measurements were in fact written in the face sheet margins, and conformed to the schematic drawings.

Sylvia Meagher was so incensed by this that she wrote to CBS News President Richard Salant. The CBS documentary was "marred by serious error and fallacious reasoning which inevitably will have misled and confused a general audience." In the case of Dr. Humes, while he insisted the measurements written in the face sheet margin were correct, "CBS failed to pursue or challenge this explanation, as in conscience it should have done, by pointing out no marginal notations giving precise measurements for any other wound, cut-down, or physical characteristic appear on the diagram; that every other entry in the diagram appears to be accurate, as opposed to the crucial bullet wound in the back; that the clothing bullet holes match the diagram, not the schematic drawings; that a Secret Service agent saw a bullet hit the President four inches below the neck; and that another Secret Service agent, summoned to the autopsy chamber expressly to witness the wound, testified that this wound was six inches below the neck."

The third part of the CBS special proved to be especially newsworthy. A portion of this segment was devoted to the JIm Garrison investigation in New Orleans, although for much of it Garrison was put on the defensive. CBS included a sound bite with Clay Shaw, who said: "I am completely innocent ... I have not conspired with anyone, at any time, or any place, to murder our late and esteemed President John F. Kennedy, or any other individual ... the charges filed against me have no foundation in fact or in law."

Most damaging to Garrison was the appearance of William Gurvich, a former Garrison investigator introduced as his "chief aide" who, Cronkite told his viewers, had just resigned from the DA's staff. Asked why he quit, Gurvich said that he was dissatisfied with the way the investigation was being conducted. "The truth, as I see it, is that Mr. Shaw should never have been arrested." Gurvich said he had met with Senator Robert F. Kennedy "to tell him we could shed no light on the death of his brother, and not to be hoping for such. After I told him that, he appeared to be rather disgusted to think that someone was exploiting his brother's death." The allegations of bribery by Garrison investigators, Gurvich said, were true. Asked whether Garrison had knowledge of it, Gurvich answered: "Of course he did. He ordered it."

Garrison himself was interviewed by Mike Wallace. Reflecting on all the bad publicity he was getting, which included allegations of witness intimidation and bribery, the DA said, "This attitude of skepticism on the part of the press is an astonishing thing to me, and a new thing to me. They have a problem with my office. And one of the problems is that we have no political appointments. Most of our men are selected by recommendations of deans of law schools. They work nine to five, and we have a highly professional office—I think one of the best in the country. So they're reduced to making up these fictions. We have not intimidated a witness since the day I came in office."

Not missing a beat, Wallace pressed on: "One question is asked again and again. Why doesn't Jim Garrison give his information, if it is valid information, why doesn't he give it to the federal government? Now that everything is out in the open, the CIA could hardly stand in your way again, could they? Why don't you take this information that you have and cooperate with the federal government?"

"Well, that would be one approach, Mike," Garrison countered. "Or I could take my files and take them up on the Mississippi River Bridge and throw them in the river. It'd be about the same result."

"You mean, they just don't want any other solution from that in the Warren Report?"

"Well," the DA replied, "isn't that kind of obvious?"

Garrison told Wallace there was a photograph in which assassins on the grassy knoll were visible. He was referring, of course, to the #5 man detail of the Moorman photograph. As he had for CBS, Ray Marcus had supplied Garrison with a portfolio of images from the picture, including the clearest copies of the #5 man enlargement.

"This is one of the photographs Garrison is talking about," Wallace told his viewers, holding up one of the Moorman pictures Marcus had given to Bob Richter. It was not the one that Marcus had recommended to Richter. Instead Wallace held up a smaller version—the smallest one, Marcus recalled, that he had given CBS. "If there are men up there behind the wall," Wallace said, "they definitely cannot be seen with the naked eye."

Marcus had urged Bob Richter to use the enlargement that the producer of the CBS New Inquiry, Les Midgley, had mis-identified as "the man who shot Meredith." Some months after the airing of the CBS documentary, Midgley was asked to reflect on the broadcasts. Echoing Walter Cronkite, Midgley said, "Nothing would have pleased me more than to have found a second assassin. We looked for one and it isn't our fault that we didn't find one. But the evidence just isn't there."

The final segment of the CBS Inquiry on the Warren Report was broadcast on the evening of June 28. It posed viewers with the question, Why doesn't America believe the Warren Report?

"As we take up whether or not America should believe the Warren Report," said correspondent Dan Rather, "we'll hear first from the man who perhaps more than any other is responsible for the question being asked." That man was Mark Lane.

Lane said that the only Warren Commission conclusion that was beyond dispute was that Jack Ruby had killed Lee Harvey Oswald. "But, of course, that took place on television," Lane said. "It would have been very difficult to deny that." Beyond that, Lane continued, there was not a single important conclusion that was supported by the facts. The problem was compounded by so much of the Commission's evidence being locked up in the National Archives where no one was allowed to see it.

The photographs and X-rays of the President's body, which represented some of the most important evidence in the entire case, were not seen by any of the Commission members, Lane said. This was a very serious shortcoming, since these films could show decisively how many wounds the President had suffered and precisely where they were located.

Rather than immediately address this, however, CBS chose to question Lane's credibility, presenting a Dealey Plaza eyewitness named Charles Brehm, who accused Lane of misrepresenting his statements in his book Rush to Judgment.

But the most notable feature in the final installment of the CBS documentary was the appearance of former Warren Commission member John McCloy. Aside from his comments to the Associated Press the previous February when the Garrison case first broke, these were his first public statements about the Warren Commission investigation. "I had some question as to the propriety of my appearing here as a former member of the Commission, to comment on the evidence of the Commission," McCloy told Walter Cronkite as their in-studio interview began. "I think there is some question about the advisability of doing that. But I'm quite prepared to talk about the procedures and the attitudes of the Commission."

The Warren Commission, McCloy said, was not beholden to any administration. And each Commission member had his integrity on the line. "And you know that seven men aren't going to get together, of that character, and concoct a conspiracy, with all of the members of the staff we had, with all of the investigation agencies. It would have been a conspiracy of a character so mammoth and so vast that it transcends any—even some of the distorted charges of conspiracy on the part of Oswald."

McCloy insisted that the Warren Commission had done an honest job. Its Report may have been rushed into print a little too soon, he said, but the conclusions in it were not rushed. McCloy did, however, indulge in a little second-guessing. "I think that if there's one thing I would do over again, I would insist on those photographs and the X-rays having been produced before us. In the one respect, and only one respect there, I think we were perhaps a little oversensitive to what we understood was the sensitivities of the Kennedy family against the production of colored photographs of the body, and so forth. But ... we had the best evidence in regard to that—the pathology in respect to the President's wounds."

At the outset of this last installment of the CBS News Inquiry, Walter Cronkite had informed his audience: "The questions we will ask tonight we can only ask. Tonight's answers will be not ours, but yours." In wondering why America didn't believe the Warren Report, CBS asked two underlying questions: Could and should America believe the Warren Report? "We have found," Cronkite said at the program's conclusion, "that wherever you look at the Report closely and without preconceptions, you come away convinced that the story it tells is the best account we are ever likely to have of what happened that day in Dallas." He criticized the Commission for accepting, without scrutiny, the FBI and CIA denials that there was any link between Lee Oswald and their respective agencies. And he criticized Life magazine for its suppression of the Zapruder film, and called on Time-Life to make the film public. Nevertheless, Cronkite said that most objections to the Warren Report vanished when exposed to the light of honest inquiry. Compared to the alternatives, the Warren Report was the easiest explanation to believe.

"The damage that Lee Harvey Oswald did the United States of America, the country he first denounced and then appeared to re-embrace, did not end when the shots were fired from the Texas School Book Depository. The most grevious wounds persist, and there is little reason to believe that they will soon be healed."