Just over half a century ago Josiah “Tink” Thompson published one of the seminal books on the JFK assassination, the influential Six Seconds in Dallas. Working with limited materials, he performed a pioneering initial investigation outlining many of the crucial objections to the Warren Commission’s conclusion of a single gunman. A striking finding at that time, made by Raymond Marcus, was the forward and then violently back-and-to-the-left head motion seen sequentially at 312/313 and 314/315 on the Zapruder film. Thompson’s original theory was that this indicated sequential shots, the first from behind and the second from the Grassy Knoll, striking in approximately 1/10th of a second.

Since the 1967 publication of Six Seconds in Dallas, intense scrutiny has been placed on all aspects of the evidence. In 1978, the HSCA discovered the DPD DictaBelt tape and an analysis concluded with a 95% confidence level that the shot that first struck the head was fired from the Grassy Knoll. In 2001, Don Thomas reanalyzed Mark Weiss and Ernest Aschkenasy’s data and published a peer reviewed article in Science and Justice concluding that the probability was even higher. Impressed by this pure science, Thompson has now changed his position and believes that the first shot came from the Grassy Knoll and that a second shot to the head came from behind less than 1 second later in accordance with the original 1978 analysis.

His new investigation, culminating in the publication of Last Second in Dallas, relies on several experts, including the distinguished Dr. James Barger who did the original acoustic analysis for the HSCA. It is to Thompson’s credit that he was able to get the reticent genius Dr. Barger to do further scientific work in the final authentication of the tape. In Last Second in Dallas, Thompson presents the reader with new observations which should erase all doubt of a single gunman in Dealey Plaza. It is a combination of the history of the case from his personal perspective of over 50 years’ experience as well as the scientific studies which have been performed with special emphasis on the acoustic evidence.

Chapters 1 and 2 are recollections of his initial reaction to the assassination as well as his early activities in the case. Interactions with many eyewitnesses and first-generation researchers and critics are recalled. Thompson revisits some of his original observations from Six Seconds in Dallas. One concerns the circuitous journey of CE399. The eyewitness testimony of Parkland Hospital Security Director O.P. Wright claiming that the bullet he recovered had a pointed tip is revived. This is a topic which has been examined in detail, but here the focus is on Wright. The author rightfully questions the ability of CE399 to have accomplished all necessary to maintain the single bullet theory. He continues with his involvement with Life magazine, which gave him access to the sequestered Zapruder film which was crucial in the writing of Six Seconds in Dallas.

Chapters 3 through 5 recount the eyewitness testimony confirming a shot being fired from the Knoll. Their firsthand recollections of the gunshot report, including the smoke from under the trees, the smell of gunpowder, footprints, and cigarette butts behind the fence, as well as the presence of an individual flashing a fake Secret Service agent badge, are telling memories of the day. The reader is exposed once again to many familiar names: the Newmans, Zapruder, Sitzman, Hudson, Altgens, Jackson, Chaney, Hargis, Martin, Smith, Holland, and Bowers. Many of these statements will be known to even beginning students of the assassination, but Thompson’s focus on the Knoll provides persuasive evidence beyond the acoustics that a shot was fired from the there.

In Chapters 6–8, Thompson recalls his continuing involvement in the case and significant developments during that time period. Deservedly proud of his work on the 1966 Life magazine article “A Matter of Reasonable Doubt,” he regales in telling how this brought him to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover. He immersed himself in the case doing groundbreaking work with interviews, examination of photos and films, and ballistics, among other fields, resulting in the publication of Six Seconds in Dallas. That book documented many of the early persuasive arguments weighing against a sole gunman and it garnered a cover story in The Saturday Evening Post. Tink’s behind-the-scenes stories are both entertaining and enlightening and provide insight into his early years of assassination research and his, at times, contentious interactions with other highly respected first-generation critics. At the time of the Clay Shaw trial, the author distanced himself from other critics who were supportive of Jim Garrison’s prosecution of Shaw. For older readers, the preceding chapters may evoke memories of the heady days of fresh clues and new revelations. For younger readers, Thompson’s firsthand recollections can directly transport them back to what those times were like.

Chapter 9 covers the involvement of Nobel prize winner Dr. Luis Alvarez, who also assumed he had a PhD in assassination “science.” Alvarez, a blatant Warren Commission apologist, is known for shooting melons, thus trying to create a reverse jet effect to explain the rearward component of JFK’s double head motion. Alvarez is one of many scientists, like Vincent Guinn, in the governmental and academic circles to have used their prestige when approaching the assassination from their individual field of expertise. Thompson recounts a long period of contentious personal communication between he and Alvarez, mainly over Alvarez’s “jiggle analysis” of the Zapruder film and “reproducing” the reverse jet effect. Critics had immediately pounced on Alvarez’s claim that a single frame horizontal blur seen at 313 reflected Zapruder’s reaction to a rifle shot, as a muzzle blast from the TSBD would not have even reached his ears yet. Ironically later in Chapter 14, a same horizontal blur will be viewed as a reaction to a shot from the Grassy Knoll, with a similar lack of success based upon similar principles. Alvarez’s attempts at shooting various objects, plus his publications, are revisited. During the writing of the book, Paul Hoch provided the author with photos and notes from the actual melon shooting sessions, which almost invariably showed objects moving forward in the direction of the bullet as had the Warren Commission tests. Thompson details the intellectual dishonesty and despicable behavior exhibited by this Nobel prize winner. I do not think the author adequately describes the enjoyment he found after obtaining Alvarez’s materials, provided by Hoch, which are now conserved at the Sixth Floor Museum.

Chapter 10 presents a continuing autobiographical tale of his life as a renowned first-generation researcher in the 70’s and a life one could well be envious of. He highlights working abroad as well as his presence at Robert Groden’s first public viewing of the Zapruder film in 1973. He also provides a behind-the-scenes view of the drama behind its first nationwide broadcast on Geraldo Rivera’s Good Night America in 1976. The electric effect this had on the public, and the resultant efforts to get the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) created, are noted. The chapter ends with the Dallas Police Department DictaBelt tapes being given to the HSCA in 1978 by Mary Farrell and its subsequent effect on their deliberations.

II

A short history of the chain of possession of the tapes is detailed and extremely helpful information on how the DictaBelt recording system functioned is provided in Chapter 11. HSCA Chief Counsel Robert Blakey’s choice of James Barger to analyze the tape for the HSCA is covered. Thompson ends this chapter without revealing to the reader that prior to the involvement of Weiss and Aschkenasy, Barger gave his discovery of the muzzle blast from the Grassy Knoll at 145.15 seconds a 50/50 probability.

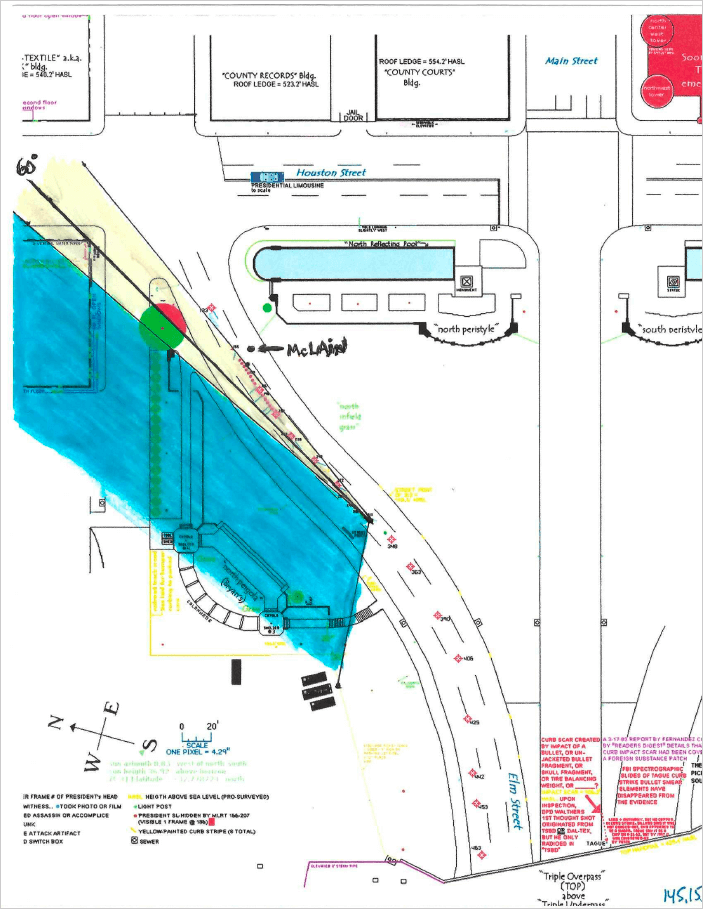

Thankfully, due to his true scientific ambivalence, the HSCA brought Weiss and Aschkenasy on board and it was their work which identified an earlier muzzle blast at 144.90 seconds. Without the identification of this earlier muzzle blast, the stalemate of medical evidence of a single shot from behind versus the acoustic evidence of a single shot from the Grassy Knoll would have continued for a significant period.

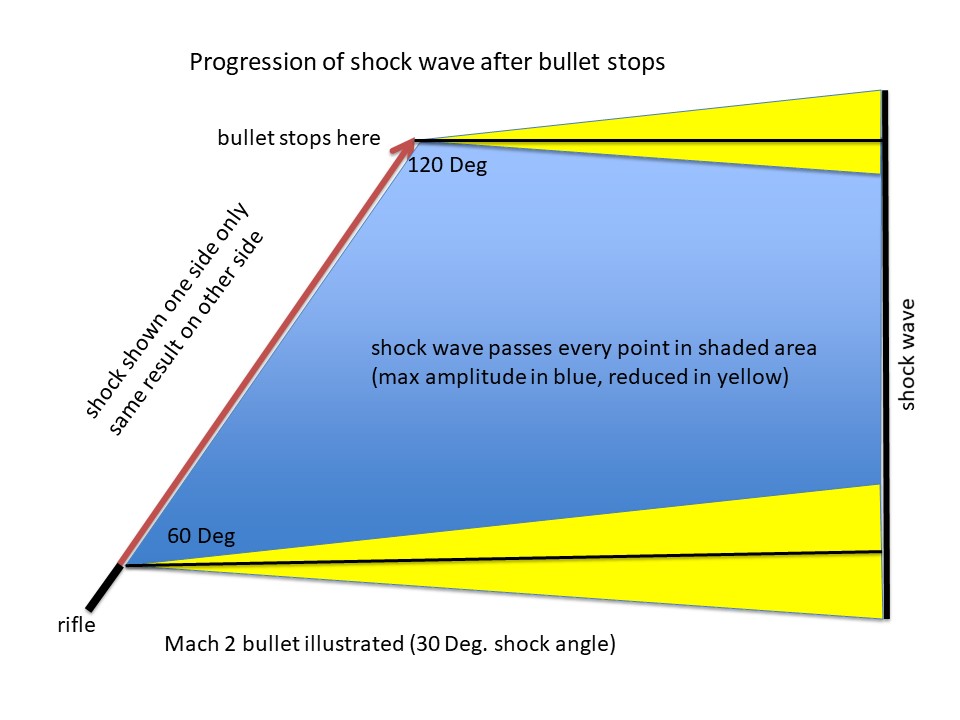

The 60 Degree Rule concerning the identification of the N waves created by a bullet’s supersonic travel is improperly explained. I brought this up with Barger, who provided a diagram he had made applicable to this when the bullet’s velocity went down to zero after impact. Most important is that when the bullet stops, the creation of the N wave stops, and it is from this point along the trajectory to the target that the 60 degrees angle is measured for a bullet traveling at Mach 2. It is not the difference in the angle between the target and microphone as stated. When applied to a Grassy Knoll shot, H. B. McLain’s microphone should not have been able to detect an N wave from any Knoll shot. Barger recently acknowledged this, but gave the explanation that it might be a reflected N wave which was recorded.

Chapter 12 delves into the HSCA investigation quickly going over Guinn’s Neutron Activation Analysis studies (today called Comparative Bullet Lead Analysis) and their attempts to synchronize shots on the tape with the film. On p. 173, a shot sequence is attempted based upon his evaluation of the timing of muzzle blasts. The origin of each shot is not noted. Confusion is created when predicated upon the inerrancy of the acoustic analysis. Barger cautioned the HSCA that, as the number of putative shots increased, so did the possibility that one of these events might be an artifact on the tape itself and not represent an actual gunshot. His warning has not been heeded.

Attempts are made in Table 12–2 to correlate reactions thought to be due to a first shot recorded at 137.70 seconds or approximately Zapruder frame 175. This has Phil Willis reacting to a shot at 202 which would not be fired until 204. Close attention must also be given to the coverage of the blurs. A blur at 181–182 is cited as a reaction to the first proposed shot at 137.70 seconds. None of the HSCA investigators in Table 12–1, on the previous page, identified a blur at that time. A horizontal panning error is mistaken as evidence for a startle reaction at 181/182 just as for 313. This is the only extra-acoustic evidence for this earlier shot.

All the reactions which are cited in Table 12–2 to support such an early shot occur incident to the actual first shot near 200 recorded at the later 139.27 seconds. The HSCA photographic panel pointed to JFK’s first reaction near 200. In this same table, it is not true that Connally and Kennedy are obscured by the Stemmon’s Freeway sign after 199. Here it is correctly stated that the last shot of the first volley, recorded at 140.32 seconds, struck Connally, but in Chapter 24 p. 352 it is mistakenly claimed that the acoustic evidence indicates that it was actually the prior shot recorded at 139.27 seconds. Mathematical calculations are not provided which would allow readers to arrive at that conclusion. This equivocation stems from a failure to recognize that the first impulse, recorded at 137.70 seconds, is an artifact on the tape. A true synchronization demonstrates the shot to Connally was fired from the TSBD and was the last shot of the first volley recorded at 140.32 seconds. The first actual gunshot which struck JFK at 201, was recorded at 139.27 seconds. The artifact on the tape earlier at 137.70 seconds is a phantom muzzle blast of which Barger had warned. A successful synchronization of a Knoll shot recorded at 144.90 seconds is not presented.

The chapter ends by briefly going over the pseudoscience of reverse jet effects and “neuromuscular” reactions which establishment scientists—like Alvarez and Larry Sturdivan—have foisted on the public to explain the backward head motion. The HSCA medical panel’s significant reservations with each is noted. Unmentioned is that the HSCA Medical Panel finally concluded that both these unlikely factors, acting simultaneously, had caused the backward head movement. Along with this is a critique of the tests performed by Alvarez with melons and the goat shooting experiments by Sturdivan at the Edgewood Army Arsenal, which helped bring the HSCA Medical Panel to its head-scratching conclusion about the cause of the violent backward head movement.

III

In Chapter 13, the decision of the AARB to buy the Zapruder film for 16 million dollars is mentioned. The unconscionable decision by the ARRB to gift the copyright of the film to the Sixth Floor Museum should have deserved mention as well. The comparative bullet lead analysis, NAA, done by Vincent Guinn for the House Select Committee on Assassinations is addressed as well as the excellent scientific work of Rick Randich and Pat Grant in exposing the fallibility of these tests. That work was so groundbreaking that the FBI has subsequently stopped using the procedure entirely. Warren Commission apologist Ken Rahn’s “Queen of the Forensic Sciences,” NAA, had been dethroned. While providing relief for some criminal suspects, this analysis did nothing to advance the case beside WC apologists having to admit these small lead fragments cannot be traced to any particular bullet.

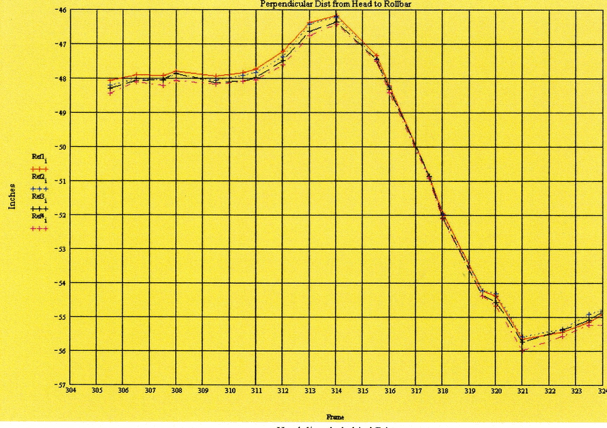

Chapter 14 begins by attempting to convince the reader that the head does not actually go forward from a bullet impact at 312/313, relying solely on head motion while ignoring contrarian observations. Even then, the author’s, Itek’s, and even David Wimp’s measurements all show forward head motion and none significant backward motion until 315 as seen on page 415. The case for the blur at 313 representing a startle reaction by Zapruder is not well made. Similar lateral blurring at frame 409 is pointed to in Photo 14–2 on page p. 198 as an example. This blur cannot be due to a gunshot report because none was fired that late. A known horizontal panning error at 409 is used as an example for what happened at 313, a supposed startle reaction. The case is completely undermined when it has already been noted on p. 117 that a blur known to be due to gunshot report at 227 is in a diagonal or downward direction just like the blurs at 318 and 331. Don Thomas is relied upon to prove that the horizontal blur at 313 was caused by an acoustic startle reaction on Zapruder’s part. Thomas’s diagram, Plate 2 on p. 214, has Zapruder reacting in ½ a frame or .027 seconds after the muzzle blast arrival. Yet, the fastest acoustic startle reaction experimentally documented by Landis and Hunt in 1939 was .06 seconds or a full Zapruder frame. Based on the other shots, Zapruder’s reaction time can be calculated to approximately 1.5 frames.

The horizontal blur at 313 cannot be due to a startle reaction and can be correctly recognized as a horizontal panning error as can 409. The other blurs at 331 (p. 227 photo 15–25), 318 (p. 223 photo 15–7), and 227 (p. 117 photo 9–20) are all greater in degree and all show a downward not horizontal deviation of Zapruder’s camera. Here the blur at 318 is not recognized as a startle reaction, yet the HSCA investigators did. Alvarez is now invoked to claim that oscillations caused the inconvenient downward camera deviation with blur at 318. None of the other blurs show such a train of oscillations as Alvarez claimed happened at 318. No such oscillations have been reported in the medical literature. If true, the downward oscillation at 318 caused an even greater blur than the supposed original horizontal reaction at 313. A startle reaction at 318, indicating a shot origin even farther than the TSBD, is antithetical to both Alvarez and the author’s claims.

In Chapter 15, the author, having found an ally in Dave Wimp in the previous chapter, continues with the use of chosen experts. In 2005, Keith Fitzgerald sought out Thompson to show him what he thought was a notable finding concerning JFK’s head motion. Fitzgerald pointed to a 1.7 inch forward head motion between 327/328 as evidence for a shot having struck from behind. A second bullet striking the head from behind and fragmenting provided an apparent answer for all the damage to the windshield and Connally’s wrist wound which his theory demanded. However, earlier Thompson had relied on the opinion of physicist Art Snyder that a 2.16 inch forward head motion between 312/313 caused by a bullet was impossible. Is the short .4 inch difference between these two measurements the difference between possible and impossible? No. The author selectively uses one expert, Snyder, to claim no rear entry at 313, but then readily accepts the antithetical opinion of Fitzgerald to propose an absolutely necessary rear entry at 328. This chapter acknowledges that the bullet struck at 328. Whatever force caused the earlier forward motion Fitzgerald had identified between 327/328 could not have been caused by a bullet impact occurring at 328. Perhaps it might be related to the application of the brakes and/or the effects of gravity on a near lifeless body.

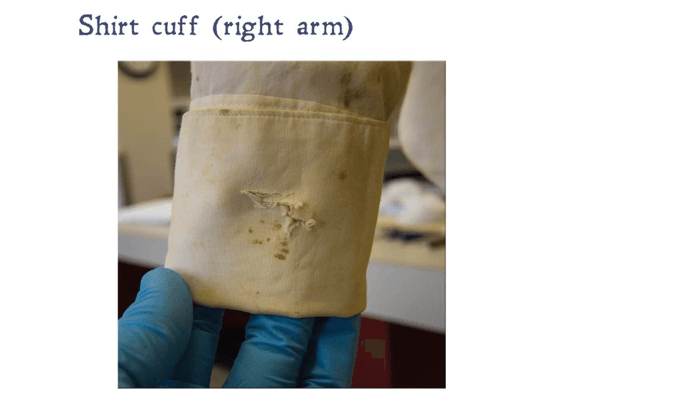

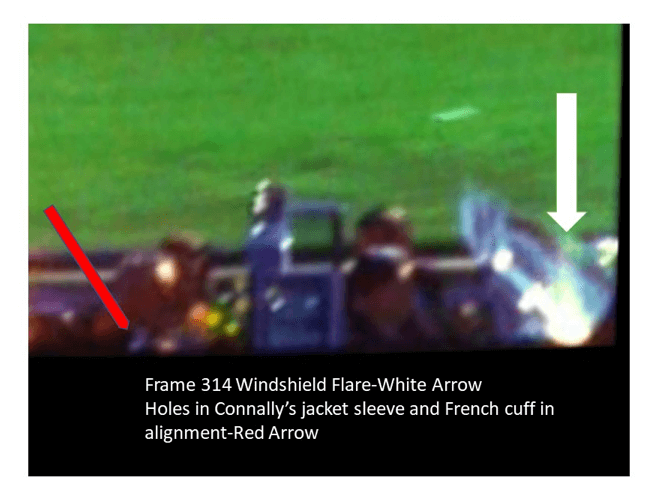

The problem for a theory of a single shot from the front at 313 means that the two points of windshield damage and Connally’s wrist wound must have all been made at the same time by fragments of a forward moving bullet at 328. Thompson is relying on Fitzgerald’s errant conclusion to reinforce his particular viewpoint. The WC testimony of Dr. Gregory is quoted here, as it was in Chapter 4 of Six Seconds in Dallas, citing his opinion that a fragment of a bullet caused Connally’s wrist wound rather than CE399. A critical revelation in the first book, omitted here, is that dark wool suit fibers were discovered in the wound. The entry holes in the jacket sleeve and French cuff must have been in alignment to have been pierced simultaneously. At frame 328, however, Connally’s French cuff is completely exposed out of the jacket sleeve. This is readily apparent in Photo 15–41 on page 233. The entry point in the jacket sleeve graphically depicted in the close-up photos is closer to the wrist than is diagrammed. In either case a bullet entering at any point in the jacket sleeve could not have entered the mid portion of the fully exposed French cuff to simultaneously carry dark suit fibers into the wound. This observation, in and of itself, makes this whole thesis untenable. See photos 1, 2, and 3.

Attention is now directed to the windshield damage. An impact at 328 is demonstrated by a flare of reflected light one frame later at 329 as the glass was deformed by a bullet’s impact. This seems quite logical. The acoustics indicates an impact at 328, a flare from deformation is seen on the very next frame and Zapruder’s startle reaction deviating his camera downward at 331. Incontrovertible evidence is provided for a gunshot and impact less than one second after the head wounds, meaning at least two gunmen.

This is the single most important observation in the book and, quite frankly, the history of the case. Without it, there is no convincing visual evidence for an impact at 328 as the acoustic evidence indicates. The author’s seeming agnosticism relating to this flare is curious. This critical observation is dismissed simply as a matter of coincidence with a single critical angle to the sun causing the flare coincidentally timed one frame, 1/18th of a second, after a known windshield impact. However, there was another earlier flare from the windshield at 314, smaller the first time because it was caused by only a fragment of a bullet. See photo 4, frame 314.

Two flares, each occurring on the very next frames after separate impacts, is evidence that the first wound to the head came from behind. The dark wool fibers in Connally’s wrist wound are fully corroborative. After the fragment’s impact at 313, Connally’s right wrist and French cuff were propelled fully forward out of the jacket sleeve. At frame 328 the holes in the jacket sleeve and in the French cuff were misaligned as photo 15–41 depicts. Selective use of observations is used to arrive at conclusions. The windshield flare at 329 will be cautiously pointed to as possible evidence of an impact but a second earlier flare, indicating a bullet going forward through JFK’s head at 313 and fragmenting, will be ignored in absolute deference to the acoustics. The presence of two flares, as well as two corresponding startle reactions, answers a question left unaddressed by the WC, whether the two points of damage were made at the same or separate times. The effects of two impacts are seen in less than one second proving conspiracy. An unshakeable belief in the inerrancy of the acoustic analysis prohibits the author from acknowledging these antithetical observations of the wound to Connally’s wrist and the presence of two windshield flares. A whole bullet directly struck the windshield frame at 328 bending its tip in the process and falling back into the limo where it was later recovered during the initial limo inspection. This non-fragmented bullet with a bent tip was chronicled by autopsy attendee and WH physician James Young MD in his 2001 US Navy BUMED Oral History Interview as well as in a confidential letter sent to ex-Warren Commission member and ex-President Gerald Ford. The existence of this whole bullet is also antithetical to a bullet fragmenting after a rear impact at 328.

The final portion of the chapter is a review of eyewitness statements with the proposition that the final shot heard was the one which is conjectured as going forward through the head at 328. The question is not if an additional shot was heard after the head exploded, the tape reliably tells us that down to the hundredths of a second. The question is whether this final shot could accomplish all that is necessary in this scenario. Connally’s exposed French cuff and the head motion beginning at 327 rather than 328 should guide us to the conclusion that it cannot.

IV

Chapter 16 deals with the medical evidence and, I must admit, it is not the strongest chapter. Having investigated this area for 30 years, I can say that it can seem extremely complex at first and that there are many pitfalls which can be, and are, run into in this chapter. Numerous problems with the autopsy are highlighted. Thompson believes that the controversy over the autopsy findings is related to incompetence rather than a concerted effort to hide evidence of conspiracy. This reviewer can not come to the same conclusion.

The Parkland doctor’s testimony concerning the head wounds, which are supposedly in contradiction to the autopsy photos and x-rays is revived, indicating to some alterations or forgery. This is a longstanding rabbit hole from which some are unwilling to exit. The hole in the skull was made by bone loss. All five of the recovered skull fragments are seen being ejected on the Zapruder film. The bone loss seen on the post-mortem radiographs and photographs in the autopsy room matches the bone loss seen as it occurred on the Zapruder film taken in Dealey Plaza as the events happened. Any intervening testimony by Parkland observers which challenges this is incorrect and only goes to demonstrate the fallibility of human recollections, such as those of O.P. Wright and McClelland among many others.

An emphasis is placed on the distribution of metallic fragments in the head seen on the lateral skull x-ray. In either scenario, back then front or front then back, there were two bullets which struck the head and both fragmented. In either case, what the lateral x-ray of the skull shows is a composite of metal particles from two bullets. These metal fragments were mobile, and many were moved out of, or about in, the skull when the temporary pressure cavity caused an explosive wound. Mobile brain tissue with enclosed metallic fragments fell out onto the gurney in Trauma Room One. The discovery of a few additional metallic fragments adds little to the discussion.

The subject of missing autopsy photos is taken up. Waters are muddied by bringing up the 30 year old recollections of Sandra Spencer to the AARB. Spencer initially developed and briefly saw the photos on one occasion shortly after the autopsy. The photographic and documentary records do not support her recollections. The HSCA had Kodak make enhancements of the roll of film exposed to light by Secret Service agent Kellerman the night of the autopsy. These images could not have been altered. I, as well as a few others, have seen these photos at the National Archives and I can say, as they have, that it is the same body on the same table at the same time and matches the other autopsy photos in the National Archives as well as those in the public domain. In the clinical photos taken later, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the fracture pattern on the photos and the authenticated skull x-rays. Spencer’s claim of a picture of the brain next to the body on the autopsy table makes no sense from a forensic perspective. The case is also made for other missing autopsy pictures. The possibility of missing photos can never be eliminated. Would one expect autopsy physicians, who will not disclose the distance of the entry wound above the EOP, to provide clear pictures of its exact location?

Unable to make sense of the medical evidence as a whole, the author simplifies the focus down to only three findings. The first concerns the location of the entry hole in the rear of the head. Thompson claims that the hole of entry with internal beveling was completed by the portion of the hole in a corner in the late arriving triangular Delta fragment. A good student of the medical evidence will know that he is quoting autopsy pathologist Dr. Boswell from his gaffe filled 1992 JAMA interview. The problem is that the Delta fragment had external beveling in one corner not internal beveling. None of the late arriving fragments had internal beveling. Boswell had unwittingly revealed his knowledge that the Delta fragment fit at the top rear as the Nix and Zapruder films show. The actual level of the entry hole documented by the autopsy team can be seen on page 265 photo 16–14. A fracture, created by a first bullet’s entry, is present at the autopsy team’s lower entry level. This extends upwards and anteriorly to stop the propagation of a fracture from the HSCA’s higher “entry” wound. This is Puppe’s law which states that a primary fracture will stop the propagation of a secondary fracture by virtue of the pre-existing gap in the bone.

This was the basis for an article I submitted to the Journal of Forensic Sciences in 1996 indicating two shots to the head, the first from behind and 1/10th of a second later from the front just as Thompson proposed in 1967. This was sent out for and passed peer review, but the editors and board refused to publish it for some of the same reasons later given to Don Thomas when his paper was even refused evaluation by Journal of Forensic Sciences.

The second finding relates to the distribution of metallic fragments in the head. These mobile fragments cannot be used as a reliable path of the bullets. The pattern of intersecting fracture lines in areas of minimally displaced skull manifesting Puppe’s law indicate that the autopsy doctors were correct in their lower entry localization.

The third area is the proper location and orientation of the Delta fragment. In 1967 in Six Seconds in Dallas, Thompson astutely identified it sliding backwards across the trunk on the Nix film. From the previous chapter, page 232, Jackie’s detailed and accurate description of the skull fragment she recovered matches the Delta fragment. Arising from this position, the only orientation possible, determined by a portion of cranial suture, is for the metallic fragments in its one corner with external beveling to match up with the 6.5 mm lead fragment seen at the HSCA’s higher “entry” point. Any proposed shot from the front had to strike the top rear of the skull to cause external beveling and deposit a 6.5 mm metallic fragment in the skull as well as simultaneously depositing lead particles in the corresponding corner of the Delta fragment. The apparent trail of metallic fragments high on the lateral skull x-ray, Photo 16–14 p. 265, do not depict a single bullet’s precise path for reasons discussed. The lower fracture, demonstrating Puppe’s law, which has passed peer review, indicates a first shot from behind and the external beveling at the HSCA’s higher “entry” means a second shot to the head from the front impacting at the top rear: forward at 313 and nearly immediately backward at 315 just as the author had proposed in 1967. These closely spaced motions corresponding to two muzzle blasts identified one quarter second apart at 144.90 and 145.15 seconds on the acoustics belt.

V

In Chapter 17, Thompson reveals that, while riding his classic BMW motorcycle through the beautiful central California countryside, he had an epiphany that the acoustic evidence was the glue which could bring all the elements of the assassination together. The findings of Wimp eliminated a forward strike at 313 as did the opinion of Snyder. Discarding the opinion of Snyder, Fitzgerald’s findings were accepted as evidence for a shot entering the rear at 328. Insufficient mathematical effort has been applied. On page 277, two essential claims are made about successful synchronization of a putative Grassy Knoll shot striking at 313 with the ensuing impact at 328, a 15 frame difference, and the preceding impact at 223, a 90 frame difference. The time difference for the last two shots is .71 seconds but the math is not demonstrated nor is it stated that it needs to be lengthened by 5% to compensate for time compression as the DictaBelt recorded. .71 X 1.05 = .7455 seconds .7455 seconds X 18.3 frames/second = 13.6 frames not 15 frames. The second claim is mathematically disproven as well. Here, the stated time difference to the previous shot was 4.8 seconds, which on this occasion is correct, because they were recorded 4.58 seconds apart and 4.58 X 1.05 = 4.8 seconds. It is not explained to the reader that compensation for time compression has been made or the reason for needing to do so. 4.58 seconds X 18.3 frames/second = 88 frames not 90 frames. For the acoustic evidence to be valid, it must synchronize with the events and this is a matter of mathematical calculations. This lack of synchronization means the echolocation of Weiss and Aschkenasy is in error. This failure of synchronization is due to the failure of W&A’s echolocation of the shot’s origin. They did not fail to correctly identify the precise timing of a true positive muzzle blast. The head is struck first from behind. It is surprising that this discrepancy in frames was overlooked. In full transparency, the math calculations immediately preceding are not in any way all that needs to be taken into consideration when doing a full synchronization. The speed of bullets at distance, speed of sound, distances, Zapruder camera rate, muzzle blast delays, and time compression among other factors must be taken into consideration. Even after a full set of calculations has been performed, as I have, a Grassy Knoll shot at W&A’s 144.90 seconds does not synchronize with either the preceding or ensuing shots which each synchronize with each other. The head is first struck from behind.

The DOJ’s response to the HSCA’s recommendation on further study of the Bronson film for movement in the 6th floor window and the acoustic evidence of recorded gunshots is reviewed. Alvarez’s timely entry into this new aspect of the assassination is noted. His activities in declining chairmanship in the Ad Hoc Committee while maintaining a dominating role as a member of the panel are detailed as are some of the panel’s inner workings. Alvarez’s scientific bias is fully exposed by recalling his previous efforts to quash satellite evidence of a nuclear explosion in the Indian Ocean in 1979 during the Carter administration. Barger’s heroic efforts in defying the Ad Hoc Committee are chronicled including threats to his professional career if he did not sign a pre-drafted statement saying he agreed with the Ad Hoc Committee’s conclusions. Alvarez is fingered as this scientific extortionist.

Chapters 18 through 23 are an excellent historical review of the DPD tape and the Ramsey Panel’s subsequent involvement. This covers Steve Barber’s discovery of the phrase “Hold everything secure,” a statement which was made shortly after the assassination, but on the tape supposedly occurred at the same time the Barger’s putative shots had been identified. The Ramsey Panel did not then need to do any statistical challenge but instead now used the ill-timed phrase “Hold everything secure” to completely discredit the possibility that the tape was recorded in Dealey Plaza or at the time of the shooting. This controversy would persist until resurrected by a peer reviewed article by Don Thomas in Science and justice, a statistical review substantiating the echolocation done in 1978 by Weiss and Aschkenasy. Thompson provides commentary on the scientific tennis match played out on the pages of the UK based journal Science and Justice between Thomas and the remnants of the Ramsey Panel, which had been dominated by his and Barger’s old nemesis Luis Alvarez. The author carefully goes over the significance of episodes of crosstalk such as “Hold everything secure” and “I’ll check it,” some of which the Ad Hoc Committee ignored, which bolstered Thomas’s position. As with the autopsy doctors, Thompson questions whether the panel’s actions were malignant but in the end is willing to chalk it up to complicity. Many readers may disagree with this opinion after reading this section. The 2005 Ramsey Panel’s belated rebuttal in Science and Justice to Thomas’s original 2001 piece had flaws which gave Thomas the advantage. Thomas served up another rebuttal with, now author, Ralph Linsker lobbing back a final article in which he admits that valid crosstalk of the phrase “I’ll check it” could destroy their argument about the late timing of the shots.

Thompson, in his quest for final validation of the tape, then turned to the premier expert in the field, Dr. James Barger. Barger has impeccable academic credentials and is in every manner a gentleman and a scholar. His strong ethics and belief in his findings did not allow him to bow to pressure from others in the scientific community particularly from Alvarez. His intellectual talents are readily apparent in Appendix A. It is to Thompson’s credit that he brought such a genius on board. Barger and Mullen’s scientific work for this book served up the match winning ace for its authenticity. In somewhat technical but understandable terms, the author lays out how this analysis was performed. True to his nature, Barger did not want to directly perform the tests as it might appear biased so instead he had Dr. Richard Mullen perform them. Thompson describes the suspense he felt when Mullen presented his findings to them for the first time. One can feel his electric anticipation. It turned out that “I’ll check it” was a true example of crosstalk establishing its authenticity. Thompson felt not only vindication of its authenticity but also validation for the opinions of Wimp, Snyder, Fitzgerald, Thomas, and, of course, Barger, who were all supportive of his theory. Barger had cautioned the HSCA that any putative shots must be matched to visible reactions seen on the Zapruder film. Not only must the acoustics be applied to events on the film, but the events on the film must be applied to the acoustics. Thomas’s 2001 article was only a statistical analysis of the echolocation for an initial shot to the head from the front. This proposition had not been challenged by the real time events seen on the film or a full mathematical synchronization of this proposed shot to the others.

Previously it has been noted that there is another flare at 314, that Connally’s right wrist could not have been struck at 328 and that horizontal panning error at 313 could not have represented a startle reaction from a Grassy Knoll shot. In 1978, Barger had initially given his Grassy Knoll shot at 145.15 seconds a 50/50 probability. The logical solution to this conundrum is that Thompson was correct in 1967. Weiss and Aschkenasy did find a muzzle blast at 144.90 seconds, but their echolocation failed, and what they actually discovered was the muzzle blast for the first shot to the head from behind consistent with Puppe’s law, the first windshield flare and proper synchronization. Barger had initially and correctly identified the shot from the Grassy Knoll at 145.15 seconds. This second impact ejected the Delta fragment from an area of previously undisturbed skull at the top rear. Two closely timed shots, recorded ¼ second apart, accounted for the rapid forward and then backward motions of the head seen at 312/313 and 314/315. When these two closely recorded shots are considered, a faithful synchronization of film and tape can be, and has been, accomplished. Chapter 23 again reviews the issues and tests which led to establishing the tape’s authenticity and how good science has prevailed over bad science.

The final chapter will be a disappointment for those who had expectations that this book would provide the exact timing and origin of all the shots. Incontrovertible evidence of conspiracy is provided, however. The film of the assassination and now the authenticated soundtrack recorded as McLain’s motorcycle traveled through Dealey Plaza should have allowed a synch to be accomplished. A purported single shot from the Grassy Knoll recorded at W&A’s 144.90 seconds does not mathematically synchronize with any of the other shots which all synchronize with themselves. Confusion related to the presence of a phantom first shot causes an inability to locate the origin of any of the shots fired in the first volley. The fourth paragraph on page 352 states that the shot to Connally’s chest came from the Dallas County Records Building, but the previous paragraph stated that the acoustics indicated this shot was fired from the TSBD. A mathematical synchronization of the shots is not accomplished. To fully synchronize the tape and film, no one avenue of investigation, not even the acoustics, is immune to challenge from other disciplines and known facts. In this regard, I find the theory that JFK’s head was initially struck from the front untenable from numerous avenues. The book’s final determination of conspiracy is left to the evidence surrounding the final volley and the most critical observation of the second windshield flare at 329.

In many ways, this is an exceptional book. Thompson, through this work, with the assistance of Barger and Mullen, has provided a scientific basis for the authenticity of the DPD DictaBelt tape. He has brought to light one of the windshield flares only one second after the head wounds indicating an additional shot and indisputable evidence of conspiracy. We are treated to a historical life’s journey through the Kennedy assassination from its beginning continuing forward through today that readers will find both illuminating and entertaining. The scientific battle over the authenticity of the acoustic evidence and his efforts in its validation will surely be one of the hallmark moments in the history of the case and an epic victory for those who believe in true versus pseudoscience. Despite its flaws concerning the number and timing of the shots, Last Second in Dallas presents new incontrovertible evidence which demands a conclusion of conspiracy. It is highly recommended reading and should be regarded as a significant book in the history of the JFK assassination.