The Criterion Collection is quite literally an invaluable asset in the world of modern day DVD releases. Criterion pioneered both the audio commentary track and the use of supplemental features per DVD release. The last film I saw of theirs was the excellent three disc DVD of The Battle of Algiers.

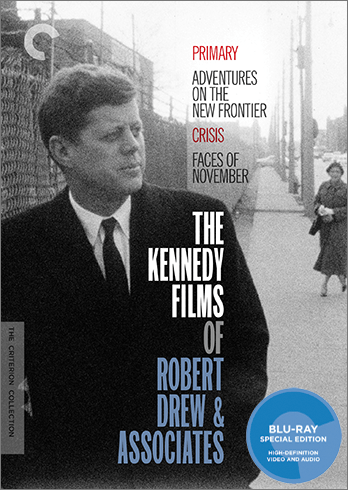

They have now released another valuable production. This one is called The Kennedy Films of Robert Drew and Associates. It consists of four documentary films: Primary, Adventures on the New Frontier, Crisis, and Faces of November. Robert Drew was a reporter and photographer for Time Inc. While on a study break at Harvard he began to explore why documentary films were so dull and uninvolving. When he returned to Time Inc. he began to attempt to break out of the confines that documentary film had slid into.

What Drew wanted to do was to make a revolution in technique. He wished to dump the reliance on narration, on music and slick camera work that consisted largely of long takes or tracking shots. He also wanted to jettison the device of the interview. In fact he wanted the filmmaker to ask no questions of his subjects at all. And further, he did not want to even tell them where to sit while he was filming. This type of documentary film came to be known as cinema verité, or direct cinema. The revolution in documentary style that it created roughly corresponded to the revolution that French feature film directors like Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard had manufactured with the Nouvelle Vague or New Wave.

Drew managed to create a unit at Time Inc. He then brought in other film-makers who shared his same goal: to help perfect this new aesthetic. These men included D. A. Pennebaker, Albert Maysles, and Richard Leacock. To say that they succeeded in their aim does not begin to describe their achievement. Consider some of the films these men were later responsible for: Gimme Shelter, Salesman, Grey Gardens, Don’t’ Look Back, Monterey Pop, The War Room, Startup.com, Ku Klux Klan—Invisible Empire.

|

| Robert Drew |

To achieve what they set out to do there were two technical barriers to surmount. First, there had to be smaller cameras so that they could do handheld shots. That is, the camera would not be attached to a tripod, or be placed on a dolly. It was portable and could follow the subject in the shot. Second, there had to be a way to record live dialogue in sync with what the camera was seeing. By early 1960, when Drew made Primary, both those problems had been solved.

At the same time Drew was getting ready to create his revolution in film style, Senator John Kennedy was also about to create a milestone in politics. Prior to 1960 no major candidate for president had decided to lay his claim to the office by running the gamut during the primary season. Kennedy did so out of necessity. He did not have the party standing that his top three opponents—Stuart Symington, Hubert Humphrey, and Lyndon Johnson—commanded. Up until 1960, the way to win the nomination was through currying favor with the party honchos. Both on the national and state level. Kennedy decided he could not win that way. But since he was photogenic, a good speaker, and his father was willing to spend a lot of money, he could win by dominating the primary season.

So Drew approached Kennedy one day as he emerged from his townhouse in Washington. JFK asked him what he wanted. Drew said words to the effect: I want to follow you around during the Wisconsin primary with a movie camera. Kennedy asked him: why should I agree to that? Drew played his ace card. Aware of Kennedy’s writing career and his interest in history, Drew replied because if he did Kennedy would be part of a new kind of history. The candidate thought it over and said that if he did not call Drew tomorrow, then he could do it. JFK didn’t call. Drew then got in contact with Humphrey’s camp and got a similar approval. The four men were allowed to film the last five days of the Wisconsin race.

In fact, they did create something extraordinary. The film Primary is not just exceptional because of its stylistic originality. But in watching we are transported back to what seems like a different universe, one that used to be called retail politicking. In the first scene we see Humphrey emerging from what looks like a corner grocery story, where he could not have been talking to more than 8-9 people. He then shakes hands with someone outside and actually exchanges a few lines of dialogue with him.

We observe both candidates driving down barren country roads and into sparsely populated rural areas—which is where Humphrey was supposed to run strong. We see JFK standing outside a factory gate in the morning with an overcoat, shaking hands with the workers, one of whom doesn’t even look at him. We even see Kennedy signing autographs for young schoolchildren who don’t vote. (When later asked why he did such a thing during a short campaign, Kennedy replied because those kids go home and talk to their parents.) One can argue that this kind of politics does still exist today in the Iowa and New Hampshire primaries. But today even those kinds of events are well planned and then orchestrated for media effect. That was not the case back then. Because both candidates were relying on the local and state representatives to prepare the events. Therefore it was very much a hit and miss process.

The big hit for Kennedy was a large auditorium rally at a Polish Catholic Church in Milwaukee the night before the election. This scene begins with what has now become an iconic shot of JFK. The camera is behind Kennedy: a wide angle shot from behind him and above. We see him go through the crowded entrance to the stage as the crowd applauds and sings “High Hopes”. Acknowledging he was late, Kennedy quips, “You’ve been standing there quite awhile, I’ve been standing for three months.” Some have written that this was a planned shot. In one of the disc supplements, it is revealed that the wide-angle lens was a last minute suggestion, and that the cameraman decided to hold the camera over his head to avoid the crowd. In other words, it was accomplished willy-nilly.

|

| Hubert Humphrey during Wisconsin primary |

The film is spotted with various human-interest angles. For example, we watch as Humphrey does a radio interview. During the interview, the host tells the candidate he thinks he will win. After Humphrey leaves the station, the host says that he actually thinks Kennedy will win. During that rally in the church auditorium, Jackie Kennedy addresses the crowd in Polish. The camera focuses on her twisting hands, which reveal her nervousness.

The film concludes with Election Day, April 5th. We first see citizens coming into voting precincts. We watch as they enter booths, and the camera stays on their feet as they vote, commemorating their privacy. We then cut to a hotel room as the Kennedy camp watches the returns on television. Kennedy is relaxed, jacketless, slowly smoking a cigar. The early returns favor Humphrey by a 2-1 margin. But as the city of Milwaukee begins to count its votes, Kennedy makes up the difference and then surpasses his opponent. JFK ended up winning by a 56-44% margin. As he says in the film, the margin of victory was disappointing. It was not the knockout blow he was hoping to deliver in Humphrey’s backyard (Hubert was from Minnesota). Which meant they would have to go through the same exercise again in Illinois and then West Virginia. Humphrey ended up sticking around for another month.

|

| Wisconsin primary election day |

This hotel scene achieves the purest form of cinema verité. One really does feel as if one is eavesdropping. First, there does not appear to be any kind of cinematic lighting. Second, the filmmakers placed the tape recorder behind the sofa, and the microphone in the ashtray. Therefore, their presence was eliminated.

The very last scene begins with a close up on a Humphrey for president sticker on the rear bumper of a car as it pulls out and then proceeds down a lonely country road. It’s a nice metaphor for the battle continuing—but the odds now being against Humphrey. The final results of the primary season were that Kennedy garnered nearly 2 million votes, Humphrey about 600,000. Which gave JFK a large advantage in delegates at the Los Angeles convention. One which neither Johnson nor Symington—who both decided to go the traditional back room route—could overcome.

It’s hard to believe, but Primary did not get a wide release in America. Time-Life owned about six TV stations, and that was the extent of its public showing in the USA. Which tells the reader a lot about the sorry domestic distribution of culturally significant films. For, as I have shown, the film constituted an aesthetic revolution depicting a political milestone. For now the primary route would be the way to the White House for both parties. It was not until the film was exhibited in France that it garnered the recognition it deserved.

II

But a most important person in America did like it. That was President Kennedy. So much so that he agreed to do two more films with Drew. The first one was called Adventures on the New Frontier. Shot in the same cinema verité style, this is a fascinating combination of the Wisconsin primary footage, inauguration day footage, and concludes with a day in the life of President Kennedy. Because of a technical failure, we don’t actually see Kennedy’s inauguration. But we do see conversations about that famous speech between John K. Galbraith and Gov. Mennen Williams of Michigan. This is then followed by a conversation in a car between Galbraith and author John Steinbeck. The latter is fascinating, because these two experienced authors were very much impressed by the style and technique of the actual writing of the speech. And that is what they actually talk about in specifics.

|

| During the filming of Adventures on the New Frontier |

Once in office for about six weeks, Kennedy let Drew and his associates film him doing his job in the Oval Office. We see him meeting with John McCloy who he has appointed to do preliminary talks with the Soviets on atomic weapons reduction. He then meets with Arthur Goldberg, his Secretary of Labor. Goldberg had been an attorney for the Congress of Industrial Organizations, and had been influential in the merger of the CIO with the American Federation of Labor. At this time, Kennedy and Goldberg discuss a solution to an airline strike of flight engineers, and also certain strategies to counter unemployment rates. They concentrate on unacceptably high unemployment in West Virginia. Kennedy wants to rush in government surplus food supplies for any family in dire straits. After this, Kennedy meets with his chief economic advisor Walter Heller. The president wants his forecast about the future trends on the unemployment horizon. Heller tells him that unless they take some kind of action, he does not see it improving on its own.

The most fascinating part of this film now follows. First, we see Kennedy working on the creation of the Peace Corps with Williams and Richard Goodwin. Which is logical, considering the fact that the former would helm his Africa policy, and the latter would be his special advisor on Latin America. Kennedy briefly talks about how America had ignored Africa, and in the midst of the decolonization process, he wants those new countries to maintain their independence.

We then watch Williams as he meets with some leaders in the senate, including Al Gore Sr. They advise him to proceed slowly. But Kennedy is worried that if they don’t engage quickly they will be too far behind the pace of change going on right then. (If the reader has acquainted himself with the reviewer’s two essays, “Hammarskjold and Kennedy vs. the Power Elite” and “Dodd and Dulles vs. Kennedy in Africa”, the evidence reveals that Kennedy was correct in his estimate.)

Drew then follows Williams to a meeting in Addis Ababa to meet with various African leaders, including Haile Selassie. While there, Williams made his famous quote. In response to what he saw his function there as, he replied, “What we want for the Africans is what they want for themselves.” This was slightly altered by the press to him saying, “Africa for the Africans.” Since there were still certain white supremacist nations in Africa, countries like England and the Union of South Africa took offense. When Kennedy was asked about this now controversial comment at a Washington press conference, he did not back away from it. He said, “I don’t know who else Africa should be for.”

This film is a good visual bookend to Helen Fuller’s volume, Year of Trial. That valuable work is unfortunately out of print today, although one can still buy it on Amazon and E bay. But Fuller’s work, like this one, was a snapshot of the New Frontier in its first year.

III

The other request that Drew made was for a film of Kennedy’s administration in a crisis situation. Kennedy liked the idea. He replied that such a film should have been made of Franklin Roosevelt the day after Pearl Harbor. At first, Drew asked to film the deliberations of the ExComm during the Cuban Missile Crisis. But press liaison Pierre Salinger told him that would not be possible due to national security reasons. So in 1963, Kennedy suggested that Drew film what he perceived to be an upcoming showdown with Governor George Wallace of Alabama. Wallace was resisting integrating the University of Alabama, located in Tuscaloosa. This was in spite of a court ruling, based on Brown vs. Board of Education, that had gone against him. Wallace had sworn to defy the court by standing in the “schoolhouse door” in order to block entry of the two students who had been accepted by the university: James Hood and Vivian Malone.

And that was a key point: the university had accepted the two well qualified African-American students. Wallace was literally trying to hold up the court ordered admittance on his own, essentially unilaterally. Learning from what had happened at the University of Mississippi the year before, Wallace understood the political value of making the federal government act against a state governor. He also knew that the media would be out in force for the event. Therefore, there would be millions of people watching it unfold on live television. In its political impact, the confrontation had the potential to catapult Wallace onto the national stage. Which it did.

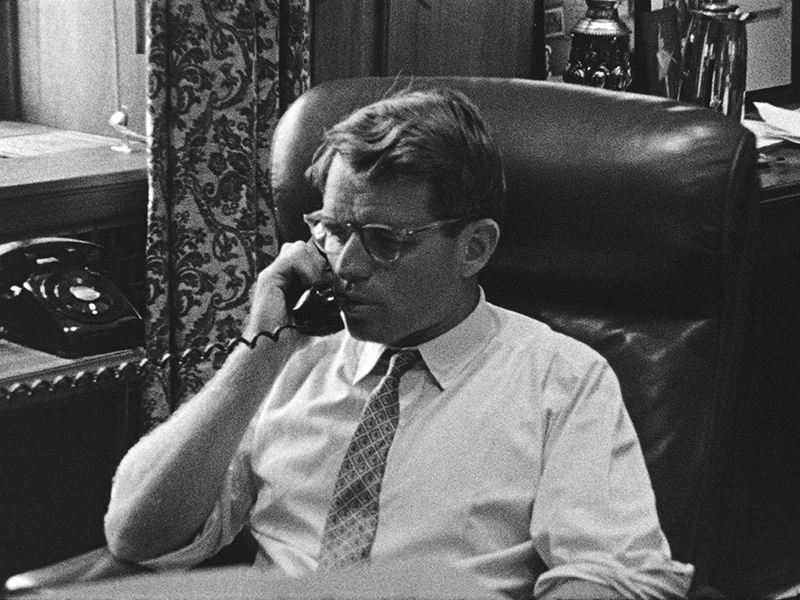

The Kennedys also learned a lesson from their experience with Governor Ross Barnett at Ole Miss in 1962. They had made a mistake and trusted Barnett’s word about the campus being secure for the entry of James Meredith. Then, when the rioting began, it took too long to get federal troops onto the scene. Two people were killed, and dozens were injured. So this time, Attorney General Robert Kennedy had tried to talk to Wallace on his home turf at the state capital in Montgomery in April and May of 1963. According to the AG, the discussions did not get very far. RFK felt that Wallace was being deliberately obscure in order to hide what he was actually planning to do. (See Robert Kennedy in his own Words, p. 185, edited by Edward Guthman and Jeffrey Shulman)

What made the potential danger more ominous was that Wallace had wired the White House the first week of June. He said that in order to keep the peace, he was bringing along 500 state guardsmen with him on the 11th. That was the date the two students were going to register for the summer session. President Kennedy wired back thanking him for the notice, but he added the only threat of violence came from the governor’s defiance of the Alabama federal court ruling. (Andrew Cohen, Two Days in June, p. 74) By the time of the confrontation, Wallace would have 825 state troopers on campus.

|

| RFK getting reports from Alabama |

Robert Drew’s film Crisis begins with a triangularly intercut sequence. We first view Wallace leaving the governor’s mansion in Montgomery by limousine for Tuscaloosa. This is followed by the two students being escorted onto the campus. We then watch Bobby Kennedy in his office getting phone reports as to what is happening in real time. As the scenes shift, the background music modulates from the southern standard “Dixie” to the national standard “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” A nice thematic touch, which accents the threat of military force.

For in light of what happened at Ole Miss, the White House had decided to mass 3,000 troops outside the campus in advance. They were under the command of General Creighton Abrams, who we see in the film on the phone with RFK, and discussing circumstances on the scene with Bobby Kennedy’s deputy Nicolas Katzenbach. For contrary to what some have written, the White House did not know what Wallace would do. And, in fact, during the film one can hear Bobby Kennedy telling his brother that they might have to just push the governor aside. And RFK had mulled over that contingency. All the way down to taking into consideration how many doors were at the entrance and breaking them down. In other words, while shoving Wallace aside, the students could enter the furthest door. But that might have provoked the spark that turned a physical altercation into a riot.

|

| Katzenbach confronts Governor Wallace |

As the film shows, the ultimate strategy decided upon was the White House nationalizing the state national guard. But first, Katzenbach approached Wallace without Hood and Malone, who had gone up to their dorm rooms. Katzenbach then asked Wallace to stand aside so the students could register for their classes. Not only did Wallace refuse to do so, he even interrupted Katzenbach as he was speaking. Therefore, Kennedy nationalized the guard. Brigadier General Henry V. Graham, with a motorized detachment of 100 of his 17,000 men, then drove up to the entrance. Graham asked Wallace to stand aside upon the orders of President Kennedy. Realizing he was completely outmanned now, Wallace did so. The students were registered under the guidance of Bobby Kennedy’s lead civil rights lawyer John Doar. Graham and his detachment stayed on campus, in the student’s dorms, for several weeks. On national television that evening, President Kennedy made his epochal speech on the issue of civil rights. The most important and compelling speech on the subject by an American president since Lincoln. Drew intercuts that speech with shots of Wallace, the students, and Bobby Kennedy watching it.

The film ends with an appropriate coda. Katzenbach calls Bobby Kennedy three days later and tells him that another black student had entered the University of Alabama at Huntsville. It happened without any repercussions. Bobby Kennedy then calls JFK and tells him about it. We watch as the Attorney General now leaves his office for the day. The battle over integrated colleges and universities had been won.

But the film depicts an interesting quote by Wallace toward the end, which informs us of the price that had been paid. Due to this piece of televised resistance, Wallace states that the south will decide the next president. This was not technically true in 1964. But Wallace’s prediction did come true in 1968—and beyond. Kennedy’s struggle for civil rights turned the south from a reliable Democratic base for presidential elections to the bastion of future Republican political power. In that way, Crisis is an historically important film.

The fourth film on the DVD set is Faces of November. This is a brief visual reverie depicting the grief which overtook Washington after Kennedy’s assassination. Drew includes here photos of Kennedy’s tomb being visited by the public in the Capitol rotunda, shots of the funeral procession, and Kennedy’s military salute at Arlington.

Criterion made its reputation by the addition of interesting and educational supplements to their DVD packages. They added four of them for this collection. Far and away the most valuable one is a joint interview with former Attorney General Eric Holder and his wife Sharon Malone. Sharon is the sister of the late Vivian Malone who has since passed away. This interview gives us some personal insight into why Vivian did what she did and what gave her the courage to persevere through it. There is also a panel presentation on Primary done in 1998 at the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles. This includes Leacock, Maysles, Pennebaker and Drew. Something like this will never happen again, since all but Pennebaker have passed away. Finally, there are interviews with authors Andrew Cohen and Richard Reeves. The former offers some insights into the film Crisis, since he used outtakes from the film for his book Two Days in June. Although Reeves is not as offensive as he usually is, still Criterion could have chosen someone else, like say Harris Wofford. Wofford worked for Kennedy in his civil rights division and authored a good book about that struggle called Of Kennedys and Kings.

Overall, this two-disc set is much worth purchasing and watching. How many DVD sets chronicle three history-making events? One dealing with our political system, one dealing with the struggle for American civil rights, and one with a stylistic revolution in film technique. This one does, which makes it unique.