David Halberstam and The Second Biggest Lie Ever Told:

A Look Back at The Best and the Brightest

Part One: Halberstam and Kennedy

|

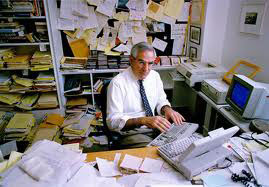

| David Halberstam works at his office in New York City on May 14, 1993 |

David Halberstam died in April of 2007 in Menlo Park, California. He was killed in a three car accident on his way to interview former NFL quarterback Y. A. Tittle for a book he was writing on the famous 1958 NFL Championship game. He was also there to deliver a speech at UC Berkeley about what "it means to turn reporting into a work of history." (San Francisco Chronicle, 4/23/07)

Halberstam wrote several books about the sports world, seven to be exact, or about a third of his total output. But he also wrote a number of books that were concerned with contemporary history. For instance, he wrote The Fifties, an examination of that decade, The Children, a chronicle of the Nashville Student Movement of 1959-62, and The Coldest Winter, about America in the Korean War.

Halberstam won a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting on Vietnam. And he wrote two books on that subject: The Making of a Quagmire (1965), and The Best and the Brightest (1972). To read the two books today is a bit schizophrenic. In the first book, the author criticizes the Kennedy administration for, as Bernard Fall wrote, not getting in early enough, fighting smarter, being more aggressive, and therefore making the other side practice self deception. (NY Times, 5/16/65) A major source for that book was Lt. Col. John Paul Vann. Vann had argued very early for the introduction of American combat troops. He had also argued that unless this was done soon, the war was lost since the military was concealing just how bad the Army of South Vietnam (ARVN) really was. For that book, Halberstam was so much in Vann's camp that he actually seemed to think that the introduction of American forces would actually win the war. (See the Introduction to the 2008 edition by Daniel Singal, p. xi) But in his second book on the subject, he argued the contrary: that America should have never gotten involved in Vietnam, Kennedy should have never sent in advisers, and President Johnson should have never made his huge military commitment.

The Best and the Brightest clearly made Halberstam's career. Previewed in two national magazines, between hardcover and paperback sales the book sold nearly 1.8 million copies. When it was first published, with one notable exception, it was met with nearly universal critical acclaim from every quarter. For about two decades, this book served as the standard popular reference work on American involvement in Vietnam. It had such a large impact on the American psyche that it created the way that many Americans saw the war and forged a paradigm through which other authors wrote about it. It would not be much of an exaggeration to say that The Best and the Brightest created a sort of Jungian cyclorama which America stood in front of and visualized the tale of American involvement in Vietnam, which the author wrote was the greatest national tragedy since the Civil War. (Halberstam, p. 667. Unless otherwise noted, all references to the book will be from the original hardcover edition.)

So how did Halberstam begin writing the book, and how did his perceptions change from 1965 to 1972? In 1967 Halberstam left the New York Times, and went to work at Harper's. There he wrote a profile of National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy. In his 2001 preface to the Modern Library edition of this book, the author wrote that it was this article that gave him the idea to do a book about how and why America had gone to war in Vietnam and also about the architects of that involvement. Securing an advance from Random House, he spent the next four years writing the book. In other words, he started his book at the time that Lyndon Johnson's massive military escalation program was failing in a spectacular way. It was a time when Johnson's war policies were being criticized by both houses of congress, much of the news media, and by a whole generation of young Americans. The latter were taking to the streets to protest the thousands of young Americans being slaughtered in the rice paddies of Vietnam, before they were even allowed to vote at home.

Clearly, John Paul Vann's advice to Halberstam, and those who would listen to him in the Pentagon, was not followed correctly. Obviously, Halberstam took notice, and he altered his viewpoint. Because of that new viewpoint, plus the promotion by Random House, plus the length of the book – well over 600 pages – and its scope, stretching back to the late 1940's, the book's publication was a matter of perfect timing. Americans wanted to read about how their country got involved in an epic foreign disaster. And they wanted more than their newspaper's day-by-day accounts, more than 400 word editorials, more than just grandstanding by ideologues of the left or right.

Halberstam gave that to them – and more. In its original hardcover printing the book runs to 672 pages of text. It has a six-page bibliography, which is divided up chronologically. But the heart and soul of The Best and the Brightest is the legwork the author did in securing scores of interviews which pepper the book. (The author notes the final tally as 500. Halberstam, p. 669)

And here emerges one of the first and most serious problems with the volume. The book is not footnoted. Therefore, one does not know where the information one is reading comes from. Does it emerge from a book, magazine article, or an interview? One does not really know. But even worse, Halberstam decided not to even list the names of the people he talked to. Which is really kind of surprising. Especially in light of the fact that so much of the book's material is based on those sources. This is an important point since Vietnam had become such a controversial subject by the time of the book's writing. It would have been instructive to know where the author was getting his information, since, in the wake of an epic foreign policy disaster, many people had a lot at stake in covering their tracks.

Halberstam tried to explain away this curious decision in his Author's Note at the end of the volume. He first writes that because of the political sensitivity of the subject, a writer's relation to his source was under challenge. Secondly, he had talked to Daniel Ellsberg, and been subpoenaed by a grand jury in the Pentagon Papers case. What he does not say is that the Pentagon Papers had already been published in book form by the time his work appeared. In other words, the court challenge had failed. Further, from what I can see, there is nothing in his book that came from classified documents. (As we shall see, this is a serious failing of the volume.) Therefore, in any academic discussion of this book, one must weigh Halberstam's decision to conceal sources against the value of full disclosure. That is, would the reader have benefited from knowing where certain information came from more than the source would have benefited from anonymity. As we shall see, because of the overall thesis of the book, it necessitated full disclosure.

What is that thesis? As I wrote above, there was one review of the book that was thoroughly and scintillatingly negative.

This was by Mary McCarthy in the New York Review of Books. (Sons of the Morning, 1/25/73) Let me quote her and then give my refinement to it: "If a clear idea can be imputed to the text, though, it is that an elitist strain in our democracy, represented by the "patrician" Bundy brothers, once implanted in Washington and crossed with the "can-do" mentality represented by McNamara, bred the monster of Vietnam." As she notes later, what Halberstam was trying to do with his book was to create the image that Vietnam was an inevitable tragedy that America walked into. And by 1966, there was no turning back, since by then the trap had been sprung. LBJ had overcommitted, and he would continue to do so until he had 540,000 combat troops in country. And that huge army would be completely undermined by the shocking effectiveness of the Tet offensive, which some have called the greatest American intelligence failure of the 20th century.

As we begin to analyze this book, it is important to keep McCarthy's review in mind. There is no doubt that Halberstam was stung by it. Since he brought it up in his author's note for the 2001 edition. The key word to remember here is "inevitable." There can be little doubt that the ultimate effect of the Vietnam War was tragic for both America and Vietnam. But was it inevitable? McCarthy did not think so. Further, she felt that Halberstam had rigged the deck to make it seem that way. She felt that Johnson could have gotten out before he escalated, but that withdrawal for LBJ was never a serious option. She was absolutely right on this point as Fredrick Logevall proved in his fine examination of Johnson's conduct of the war in 1964-65, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam.

We must note here that McCarthy wrote her withering review in January of 1973. This was after the publication of the Pentagon Papers, but many years before any serious declassification of further documents on the war. That declassification process was accelerated by the release of Oliver Stone's film JFK. This declassification process has cemented McCarthy's view of LBJ in regards to Vietnam – he never seriously contemplated withdrawal or a negotiated settlement until 1968. But this declassified record, plus the works built upon that record, shed much light on Halberstam's discussion of Johnson's predecessor, President Kennedy, and his conduct of the war. As we shall see, Halberstam's discussion of Kennedy is as lacking in detail, perspective, and honesty as is his portrayal of Johnson.

II

One of the oddest things about The Best and the Brightest is its historical imbalance. The book deals with American involvement in Vietnam from its origins – the aid given to the French in the first Indochina War – up to the Nixon administration, when the book was published. So the book spans a time period of 22 years, from 1950 to 1972. But when one examines its actual contents, the overwhelming majority of pages deal with American involvement under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. And when I say overwhelming majority, it is literally that. In this entire nearly seven-hundred-page book, the author spends 19 pages on what happened in Vietnam before Kennedy took over; he spends all of three pages on what Nixon did after the election of 1968. (Check for yourself if you don't believe me: the pages are 79-85, 136-49, 662-65) If you do the arithmetic, this comes to less than three per cent of the book. Yet, as I said, this period amounts to 15 years, twice as long as the Kennedy and Johnson presidencies. And the years before and after contain key parts of the story. It is quite surprising to me that no review of this book that I have seen has ever brought up this important point – not even Mary McCarthy's. To me, there is really not an excuse for this. The book was published in the middle of 1972. So the author had four years of looking at and reading about what Nixon had done.

And make no mistake, Nixon had done a lot. The figure of 540,000 combat troops in country came under Nixon, in February of 1969. To aid his Vietnamization program – the turning over of land combat operations to the ARVN – Nixon ordered the expansion of the war with the bombing of Cambodia. He and Henry Kissinger then sent combat troops into that country. This caused the collapse of Prince Sihanouk's government. And as authors like William Shawcross have shown, it was this overthrow that eventually led to the coming of the Khmer Rouge and the horrible atrocities of Pol Pot. Nixon also sent ARVN ground troops into Laos in 1971. As Jimmy Carter said in his famous Playboy interview, more bombs were dropped on Cambodia and Vietnam under Nixon than under LBJ.

Further, it was the Nixon administration that did all it could to cover up the fact that the My Lai massacre was part of the huge CIA program of civilian assassination secretly known as Operation Phoenix. This was done by rigging both the military investigation into the atrocity, and by commuting Lt. William Calley's sentence from life in prison to house arrest. This was done by Nixon himself.

Finally, as Tony Summers proves in his biography of Nixon, it was Nixon and his backers who deliberately scuttled any kind of peace agreement that Johnson was attempting before he left office. As Jon Weiner notes, this was done for two reasons: 1.) It increased Nixon's chances of winning a very close election, and 2.) It kept the proxy government alive in South Vietnam, with the contingent promise that they would get a better deal under Nixon. As Professor Weiner notes, this bit of realpolitik treachery probably allowed the war to drag on for years and led to the deaths of around 20,000 Americans and about a million Vietnamese.

This is some of what Halberstam left out at one end. What about the other end? That is what came before Kennedy and Johnson? This crucial period of early American involvement covers a continuum of eleven years prior to Kennedy's inauguration. How can one possibly deal with that initial investment in an adequate way in 19 pages? I don't think any scholar in this field would say that you could. There have been entire books written on just that subject: early American involvement in Vietnam prior to the Kennedy administration. In fact, the entire first volume of the Pentagon Papers, the Gravel Edition, deals with precisely that. It is over 300 pages long.

The initial American involvement is usually traced from the decision by President Truman and Secretary of State Dean Acheson to recognize the newly propped up French proxy government in Vietnam led by their stand-in Bao Dai. This was done by a letter in February of 1950 which contained both their signatures. (And it also recognized French hegemony in Laos and Cambodia.) As Halberstam points out, this was done in response to the fall of China the year before to Mao Zedong's communists. With the outbreak in Korea, the commitment was accelerated into a relatively small amount of aid to the French military. As the rebellion against the French, led by Ho Chi Minh and his military chief Vo Nguyen Giap, picked up steam, President Eisenhower and his Secretary of State John Foster Dulles greatly ramped this aid upwards. It is common knowledge today that by 1953, the USA was paying about 75 per cent of the bill to fight the French Indochina War. It was Eisenhower and Dulles who actually gave the French direct aid in air cover in both 1953 and 1954. In fact, at the climactic battle of Dien Bien Phu, 24 CIA pilots flew American planes under French insignia. This mission was a much smaller version of what the French had actually requested from Dulles, and which Vice President Richard Nixon agreed to. As John Prados outlines in his two books The Sky Would Fall, and Operation Vulture, the proposed American plan was to have the Seventh Fleet use 150 fighters to cover the bombing mission of 60 B-29s. The bombing included a contingency plan to use three tactical atomic weapons. How close did it come to happening? Reconnaissance flights were done by the Air Force over the proposed bombing site. President Eisenhower decided he needed approval from London to go ahead with the mission. This was not forthcoming. So, at the last minute, Ike vetoed it.

From here, it was John Foster Dulles who actually controlled the Geneva Agreements, which ended the First Indochina War in 1954. Dulles coordinated what was essentially a damage control operation. The USA did not sign these agreements, which gave them a fig leaf to violate them. The key point was that the country was to be temporarily divided at the seventeenth parallel and free elections were to be held in 1956 to unify the country under one leader. Dulles knew that the North Vietnamese communist Ho Chi Minh would win these elections in a landslide. So even though Dulles' representative at the conference read a statement saying that the USA would honor the agreement, and that America would not use force to upset the agreement, this was all a sham. (See Vietnam Documents: American and Vietnamese Views of the War, edited by George Katsiaficas, pgs. 25, 42, 78) Within weeks of the peace conference, Dulles and his CIA Director brother Allen had begun a massive covert operation to guarantee that Ho Chi Minh would not unify the country under communist rule. (ibid, pgs. 26, 73, 132 )They began a colossal propaganda program to scare a million Catholics in the north into fleeing to the south. Why? Because the man the Dulles brothers put in charge of that operation, master black operator Ed Lansdale, decided that the French stand-in, Bao Dai, had to go. Lansdale searched for an American stand-in. He found him at Michigan State. His name was Ngo Dinh Diem and he was a Catholic. He had also been a French sympathizer. Lansdale rigged a plebiscite vote in 1955 to get Diem and his brother Ngo Dinh Nhu into power. As predicted, and instructed, Diem then cancelled the unification election of 1956.

All of this is absolutely central in understanding what was to come later. For it was these events – Dulles' play-acting at Geneva, the almost immediate covert operation by Lansdale, the choice of Diem, Lansdale's fraudulent election that brought him to power – these are what formed the basis of the original direct American commitment. Without them, there very likely would have been no further American involvement in Vietnam. Or if there were, it would have been of a radically different character and degree.

To say that Halberstam gives these crucial events short shrift is an understatement. And a huge one. If you can believe it, he deals with them in less than two pages. (See pgs. 148-49) Recall, this is a book of almost 700 pages. Yet it grossly discounts what was probably the most important series of events in the growing American commitment to South Vietnam. Why do I say that it was so important? Because Lansdale and Dulles chose a poor long-term candidate for leadership in Diem. Especially when one contrasts him with Ho Chi Minh.

Many, many writers have described the myriad failures of Diem's rule: He was a dictator who put thousands of people to death and imprisoned thousands more. He was a blatant nepotist who placed unqualified family members in positions of power. These members then proved to be totally corrupt and enriched themselves at the government trough. As opposed to Ho Chi Minh, he and his family dressed, acted, and worshipped like Westerners. So in addition to the above practices, they could never win over the mass of peasants in the countryside. What antagonized the peasantry even more is that Diem put a halt to the redistribution of land, which had begun after 1954.

Diem's unpopularity resulted in two assassination attempts and a coup attempt by 1962. Consequently, with such a leader in place, the American commitment had to mushroom. For the simple reason that Diem inspired very little allegiance to his cause. Mainly since his cause was the perpetuation of his, and his family's power. This was exhibited by the many cases of election fraud that took place under his aegis.

By 1960, Diem's rule posed so many serious problems – for both him and America – that even the American ambassador in Saigon was asking him to make fundamental changes in order to survive. (David Kaiser, American Tragedy: Kennedy, Johnson, and the Origins of the Vietnam War, p.64) For Diem was so unpopular in the countryside that an insurgency was growing against him. The insurgency was called the Viet Cong. In fact, in 1960 the CIA predicted that unless Diem made reforms away from one man rule, secret police forces, and corruption in high places, the Viet Cong insurgency would grow and "almost certainly in time cause the collapse of the Diem regime", perhaps in as soon as a year or so. (ibid) It got so bad that in October of 1960 Ambassador Durbrow requested permission to speak to Diem about retiring his brother Nhu abroad, and even suggesting that the USA needed new leadership in Saigon. Diem resisted the entreaty and blamed all of his problems on the communists. (ibid, pgs. 64-65) But Durbrow did not relent. He angrily confronted Diem again in December. (ibid, p. 65)

At this point, the ARVN consisted of about 150, 000 men and the USA had about 700 advisers in country. Yet, even with all that, and as early as October of 1960, the CIA was saying that Diem could not survive much longer. He had to make democratic reforms. Which he resisted.

Halberstam knew all of this. Because he won his Pulitzer Prize largely based on his early reporting from Saigon, which included much material on how poorly Diem and his family were running the government. In fact, he devoted much of his first book to this subject. But surprisingly, this part of the story – the conditions produced by Diem's rule in South Vietnam prior to 1961 – is largely absent from The Best and the Brightest. This makes for another instance of imbalance. For one cannot understand the situation the Kennedy administration encountered upon entering office without that information.

III

There is a third curious imbalance in The Best and the Brightest. John F. Kennedy served as president for less than three years before he was assassinated in Dallas in 1963. Lyndon Johnson served as president for over five years, from November of 1963 until January of 1969. Further, as everyone who knows anything understands, it was Johnson who oversaw the enormous, almost staggering, military escalations: the rocket and bombing barrages, the buildup of the Republic of South Vietnam Air Force until it was the seventh largest in the world, the digging out of Cam Ranh Bay so it could become a huge Navy and Air Force base, the placement of over 500, 000 combat troops in South Vietnam, and the killing of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, as well as over thirty thousand American troops. Nothing even resembling this happened while Kennedy was in office, and there is no record of his ever contemplating any of these things. Yet Halberstam's discussion of Kennedy's Vietnam policy is 301 pages long. His discussion of Johnson's policy is 356 pages long. Again, in light of the above, this is inexplicable. Clearly, there was very much more to write about in Vietnam under Johnson, and in every way imaginable. Yet Halberstam chose not to. In fact, after page 588 – after Johnson makes the first big troop commitments – there is very little description of the many further escalations LBJ made. For example, of the bombing campaign that made South Vietnam look like the surface of the moon by 1967. Again, this is a curious editorial decision made by Halberstam.

In fact, in rereading the book for the second time, I began to take notes on all these rather odd and quirky Halberstam decisions: virtually ignoring the circumstances of the initial commitment, ignoring what Richard Nixon did later, greatly minimizing the deficiencies of the Diem regime, and granting almost equal space to both the Kennedy and Johnson policies. The net effect of all this is to:

- Make Vietnam a Democratic Party war, and

- To give American involvement under Kennedy almost the same weight as involvement under Johnson.

The problem with this of course is that it is a complete distortion of history. As detailed above, the original commitment was made under President Eisenhower, and it was engineered by John Foster Dulles. And when President Kennedy was killed, there was not one more combat troop in Vietnam than when he was inaugurated. Johnson reversed that with remarkable speed – in a bit more than one year. And by 1968, LBJ had a half million combat troops in country. Which is something that, as we shall see, Kennedy refused to do at all.

But this is just the beginning of what Halberstam leaves out in order to make his thesis work, namely that Vietnam was a peculiarly tragic American inevitability. For instance, John Newman begins his masterly book JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power, with a memorable scene. Just six days after his inauguration, Assistant National Security Adviser, Walt Rostow hands President Kennedy a pessimistic report on Vietnam. The report was commissioned by the Eisenhower administration but not acted upon by them. It was written by Ed Lansdale, the man who John Foster Dulles sent to Vietnam to prop up Diem. Quite understandably, Lansdale did not see the problems in Vietnam as Elbridge Durbrow did. He saw them as Diem did: it was the Communists fault, and to resist them he needed more American help. (Newman, p. 3) Lansdale agreed with the CIA: If there were not fast and large American intervention, Vietnam would be lost within a year or so. Since he was a total Cold Warrior, Lansdale's report then added that if Vietnam fell, Southeast Asia "would be easy picking for our enemy." (ibid, p. 4) So the Ugly American was now invoking the dreaded Domino Theory in order to get Kennedy to act. It is only suitable that it was Rostow who showed the report personally to Kennedy. Because as many commentators have shown, on Vietnam, Rostow and Lansdale were two peas in a pod: They both wanted direct American intervention in Saigon.

Halberstam also includes this episode in his book. But it appears on page 128. Newman understands its true significance, and since he is interested in demonstrating Kennedy's true actions on Vietnam, it serves for him as a perfect jumping off point. The young president is confronted with imminent collapse in South Vietnam. The two people pushing this emergency angle on him are trying to get him to eventually commit American forces to the theater. What happens to them? By November of 1961, Kennedy understood what an unmitigated hawk Rostow was and shipped him out of the White House to the Policy Planning Office at State. (Virtual JFK, by James Blight, p. 181) Ed Lansdale, who was covetous of the ambassadorship to South Vietnam, did not get it. (Newman, p. 3) In fact, like Rostow, Kennedy shipped him out of the Vietnam sphere altogether and into running anti-Cuba operations.

But further, and a point that is almost completely missed by Halberstam, this was the first request in the White House to send combat troops to South Vietnam. In his book Lessons in Disaster: McGeorge Bundy and the Path to War in Vietnam, Gordon Goldstein counts it as the first such request. He then lists seven more such requests for combat troops in the next nine months. Each one was turned down. (Goldstein, pgs. 52-58) This is significant of course for what it tells us about Kennedy. Try and find this information in Halberstam's book.

Now, another highlight of Newman's book is Kennedy's receiving of the Taylor/Rostow report and the discussion that ensued afterwards. All the 1961 requests for combat troops caused Kennedy to send Rostow and military adviser Max Taylor to Vietnam to report back on the conditions there. As authors Newman and Blight note, this report started a two-week debate in the White House over the issuance of combat troops to save Diem and South Vietnam. Almost everyone in the room wanted to send combat troops. But Kennedy was adamantly opposed to it. So opposed that he recalled copies of the Final Report and then leaked reports to the press that Taylor had not recommended any such thing – even though he had. (Newman, p. 136) Further, Air Force Colonel Howard Burris took notes on this debate. They are contained in the James Blight book. (pgs. 282-83) They are worth summarizing in this discussion of Halberstam.

Kennedy argued that the Vietnamese situation was not a clear-cut case of aggression as was Korea. He stated that it was "more obscure and less flagrant." Therefore America would need its Allies since she would be subject to intense criticism from abroad. Kennedy then brought up how the Vietnamese had resisted the French who had spent millions fighting them with no success. He then compared Vietnam with Berlin. Whereas in Berlin you had a well-defined conflict that anyone could understand, Vietnam was a case that was so obscure that even Democrats would be hard to convince on the subject. What made it worse, is that you would be fighting a guerilla force, and "sometimes in phantom-like fashion." Because of this, the base of operations for US troops would be insecure. Toward the end of the discussion, Kennedy turned the conversation to what would be done next in Vietnam, "rather than whether or not the US would become involved." And Burris notes that during the debate, Kennedy turned aside attempts by Dean Rusk, Robert McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, and Lyman Lemnitzer to derail his thought process.

The Burris memo is a pretty strong declaration of Kennedy's intent not to introduce combat troops into Vietnam. Either Halberstam never interviewed Burris or, if he did, he chose not to include the memo in the book. Whatever the reason, this impressive and defining speech is not in The Best and the Brightest.

John Newman examined this debate and came to a rather logical and forceful conclusion about it: "Kennedy turned down combat troops, not when the decision was clouded by ambiguities and contradictions…but when the battle was unequivocally desperate, when all concerned agreed that Vietnam's fate hung in the balance and when his principal advisers told him that vital US interests in the region and the world were at stake." (Newman, p. 138) As Newman notes, it does not get much more clear than that.

But Halberstam discounts this certitude. What he tends to concentrate on is the issuance of NSAM 111 on November 22, 1961. Kennedy had turned down the hawks' request for troops. But he did grant them around 15, 000 more advisers on the ground to see if this would fend off the growing insurgency.

IV

At the end of the debate Kennedy did something else that, again, Halberstam completely missed, or chose to ignore. Because it is not in his book. Realizing that his advisers and he were in opposition to each other over Vietnam, he decided to go around them on the issue. He first sent John K. Galbraith to Vietnam to put together a report that he knew would be different than the one that Taylor and Rostow had assembled. (Blight p. 129) He then gave this report to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in private. The instructions were to begin to put together a plan for American withdrawal from Vietnam. (ibid) The evidence about this is simply undeniable today. In addition to Galbraith, we also have this from Roswell Gilpatric, McNamara's deputy, who in an oral history, talked about Kennedy telling his boss to put together a plan "to unwind this whole thing." (ibid, p. 371) In addition to Gilpatric and Galbraith, Roger Hilsman also knew about the plan since another McNamara employee, John McNaughton, told him about it. (NY Times, 1/20/92) It's clear that McNamara did tell the Pentagon to put together this plan since it was presented to him finally at the May 1963 SecDef conference in Honolulu. (Jim Douglass, JFK and the Unspeakable, pgs. 288-91) He criticized it as being too slow.

Now, the record of that particular meeting in Hawaii was not declassified until the ARRB did so in 1997. But today it's there for all to see in black and white. When it was released, even the NY Times and Philadelphia Inquirer had to acknowledge it. So we cannot hold it against Halberstam that he did not have this plan or the records of this meeting. On the other hand, the man says he did 500 interviews. Are we really to believe that he did not talk to Galbraith, Hilsman, or Gilpatric? And that if he did, they all forgot to tell him about this?

Now, with McNamara finally formulating a withdrawal plan, and the situation in Vietnam getting worse in 1963, Kennedy decided to activate the plan. In late September of 1963, he sent McNamara and Taylor to Saigon in order to make another report to him about the progress of the war. McNamara, of course, understood what Kennedy wanted. In keeping with Kennedy's wishes, he asked several military advisers if their mission would be substantially reduced by 1965. (Newman p. 402) And as he also knew, Kennedy would have to keep Taylor under guard. And he did. As Newman and Fletcher Prouty (JFK: The CIA, Vietnam, and the Plot to Assassinate John F. Kennedy, pgs. 260-265) have demonstrated, the Taylor-McNamara Report was not really written by them. It was a complete back-channel operation from Washington. And the final arbiter of what went in the report was President Kennedy. One can pretty much say that instead of the two travelers presenting Kennedy with their report, the president presented his report to them. (ibid, p. 401) Consequently, the report delivered a rosy picture of what was going on in Vietnam and stated that because of this, American forces could be withdrawn by the end of 1965. It also said that this withdrawal would begin in December of 1963 with the removal of a thousand American advisers. (Newman p. 402)

Now, Taylor did not want to include the thousand-man withdrawal in the report. Kennedy insisted on it. (ibid, p. 403) The Bundy brothers objected to completing the withdrawal by the end of 1965. Kennedy, through McNamara, insisted on that also. (ibid, p. 404) In his discussion of this meeting over the report, Newman makes clear that it was Kennedy who applied the pressure to sign on to it to his mostly reluctant cabinet. Predictably, he then sent McNamara to announce the withdrawal plan to the awaiting press. As McNamara proceeded outside to address the media, Kennedy opened his door and yelled at him, "And tell them that means all of the helicopter pilots too!" (Ibid, p. 407) This, of course, became the basis for National Security Action Memorandum 263, Kennedy's order for the withdrawal to begin.

What Halberstam does with this crucial information is nothing less than shocking. Here is how he explains McNamara's escalating role in 1962-63, "He became the principal desk officer on Vietnam in 1962 because he felt that the President needed his help." (Halberstam p. 214) This is bizarre on its face. But in light of what we know today, it is faintly ludicrous. But Halberstam, as was his characteristic, then doubled down on this unfounded stretch. On the very next page, the author says that McNamara had no different assumptions than the Pentagon did. And further "that he wanted no different sources of information. For all his idealism, he was no better and perhaps in his hubris a little worse than the institution he headed. But to say this in 1963 would have been heresy…." (Halberstam p. 215)

What McNamara would have said in 1963 was that he was not working for the Pentagon. He was working for President Kennedy and Kennedy had told him to start winding down the war and have us out in 1965. In fact, McNamara did say this to the people mentioned above, he said it to the press in October of 1963 on Kennedy's orders, and he said it during a meeting with Kennedy and McGeorge Bundy. (Blight, pgs. 100, 124) As noted above, Halberstam missed all of these.

Or did he? For besides misrepresenting McNamara, the author does something even worse. There is no mention of NSAM 263 to be found in his culminating chapter on the Kennedy administration. Halberstam does mention the debate over the mention of withdrawal in the actual report. (p. 285) But he does not say that the report was the basis for the NSAM ordering withdrawal. And he does not say that the report was supervised by President Kennedy and presented as a fait accompli to Taylor and McNamara. Further, he never mentions that it was Kennedy who got the recalcitrant members of his staff to sign on to the report.

And Halberstam misses the whole point about the rosy estimate of the American war effort in Vietnam. He tries to write it off as all wishful thinking so Kennedy can put off decisions into the indefinite future. (p. 286) As Newman makes clear in his book, Kennedy understood that the intelligence reports were wrong. But he was using them to hoist the military on its own petard. The military understood this too late, and they tried to change their reports and even backdated them. (Newman, pgs. 425. 441) But there was enough left of them for Kennedy to pull off his bit of subterfuge. In fact, McNamara understood this and asked certain agencies in the State Department to give him more optimistic estimates, which he could use to figure the withdrawal plan around. (Blight, p. 117) Halberstam mentions that the intelligence figures changed in November 1963, but he never makes the connection as to why. (p. 297)

How does Halberstam sum up Kennedy's stewardship of Vietnam? He writes that it "was largely one of timidity." (p. 301) Well, if one eliminates Kennedy's withdrawal plan and NSAM 263, if one misrepresents what McNamara was doing, if one cuts out the SecDef Conference of May 1963, and the fact that Kennedy stage-managed the Taylor-McNamara Report to announce his withdrawal plan – if one does all that, then I guess you can use the word "timid" to describe Kenendy's Vietnam policy. But that is also practicing censorship of the worst kind: it is spinning facts in order to arrive at a preconceived conclusion. The one Mary McCarthy characterized as Vietnam being an inevitable American tragedy.

If it appears that I am being tough on Halberstam here, I'm really not. Because there is no giving him the benefit of the doubt on this one. Halberstam says he read the Pentagon Papers. He writes that, "…they confirmed the direction in which I was going…." (p. 669) Yet in Volume 2, Chapter 3, of the Gravel Edition of the Pentagon Papers, the following sentences appear:

Noting that "tremendous progress" had been made in South Vietnam and that it might be difficult to retain operations in Vietnam indefinitely, Mr. McNamara directed that a comprehensive long range program be developed for building up SVN military capability and for phasing out the U.S. role. He asked that the planners assume that it would require approximately three years, that is, the end of 1965, for the RVNAD to be trained to the point that it could cope with the VC. On July 26, the JCS formally directed CINPAC to develop a Comprehensive Plan for South Vietnam in accordance with the Secretary's directive.

Does it get much more clear than that? These sentences appear right at the beginning of the volume. But they are part of a chapter entitled, "Phased Withdrawal of US Forces, 1962-64." This chapter goes on for forty pages of the volume, 160-200. The best assumption one can make here is to say Halberstam was just plain lying about reading the Pentagon Papers. On the other hand, if he did read them, he could not have missed this. He had to cut it out precisely for the opposite reason he gives: they did not confirm the direction in which he was going. In fact, they actually contradicted it. Kennedy did have a withdrawal plan going in late 1963, one that Halberstam does not spell out or even seriously mention. And if he had not been assassinated, he may have completed it after his reelection.

But this would have completely messed up the thesis of the book. And it would have rendered pointless all those boring mini-biographies of the men involved in Vietnam decision-making. (The one on McNamara goes on for 25 pages, 215-240) But this perhaps explains why Halberstam very much soft-peddles – or does not mention at all – Kennedy's actions in the Congo, where he favored leftist rebel leader Patrice Lumumba; or his speeches going back as far as 1951 assailing the boilerplate Cold War platitudes of both Acheson and John Foster Dulles; or his attacks on French colonialism in both Vietnam and Algeria. If he had not short-changed these, or eliminated them, then Kennedy's withdrawal plan would make even more sense to the reader.

But then the epic American tragedy of Vietnam would not have been "inevitable." And Halberstam would have had to have written another book. One in which he had to give credit to Kennedy for his wisdom and foresight in knowing when to run around his cabinet. In fact, in the taped conversation noted above between Kennedy, McNamara, and Bundy, this point is dramatically illustrated. For when McNamara mentions the withdrawal plan, Bundy reveals that he does not know anything about it. Yet, recall, Halberstam started his book based on a profile of McGeorge Bundy and his influence on the Vietnam War. When, in fact, the truth was that Kennedy understood that Bundy was too hawkish and decided to go around his National Security Advisor. Bundy did not realize what Kennedy had done until he heard the conversation played back to him three decades later. (Blight, p. 125)

Yet Bundy is the man that Halberstam felt controlled the decisions on Vietnam. This is how flawed The Best and the Brightest was at its inception. The author proceeded anyway. Even when the Pentagon Papers ruined his thesis.