Oswald’s alleged trip to Mexico City in late September of 1963 has been the subject of abundant research and controversy. There has been much discussion about whether or not he actually took the trip to Mexico, and if that strange voyage was somehow connected to the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The FBI, at the behest of President Lyndon Johnson, investigated the murder of the young president. In public at least, the Bureau and the Warren Commission declared that their probe led to the discovery that Oswald was seen sitting beside a man named John Howard Bowen on a bus bound for Mexico City. The FBI eventually discovered that Bowen was an alias. The man’s real name was Albert Osborne. Their investigation of Osborne, as can be expected, was not complete.1 Because of that fact, a mythos about the strange figure of Albert Osborne sprung to life in assassination literature. Even the late diehard Warren Commission defender Vincent Bugliosi wrote that “many of the questions about Osborne-Bowen remain unanswered.”2

The liveliest piece of disinformation about Osborne was printed in The Torbitt Document, sometimes called Nomenclature of an Assassination Cabal. There, Osborne is actually supposed to be in charge of recruiting the assassination team from Mexico. And in October of 1963, he is depicted as having been in New Orleans meeting with Clay Shaw and CIA associated attorney Maurice Gatlin. As is the case throughout that misleading pamphlet, there is no proof provided for any of these claims. But the evidentiary problems about Osborne stemmed from the fact that he was an enigmatic and interesting character who told many lies to the FBI. Furthermore, the man seemed to have no steady source of income to finance his many journeys from Mexico, through various parts of America, and to Europe. But even with all the mystery about his traveling and his identity, the Bureau stopped investigating him in March of 1964 without ever establishing what, or even if, he had a job. It is difficult to place the circumstances of Osborne’s life at that time into any kind of legitimate employment. He himself told stories about what he did for a living, and as we shall see, those who knew him had suspicions he was involved in espionage work.

This article will continue the investigation into the life of Albert Osborne and will also provide a brief outline of the life of the real John Howard Bowen. We will conclude with a short discussion about whether or not the two ever met.

In the Beginning

Albert Osborne began his life in Grimsby, England on November 12, 1888 3 (Appendix 1). He was one of 12 children born to his father James, a fisherman, and his wife Emily.4 He attended St. James Academy in Grimsby until the eighth grade before leaving school.5 He worked as a grocer and served in the militia before enlisting in the British Army on December 12, 1906, at the age of 186 (Appendix 2).7 After joining the army he was sent abroad to serve in different posts in the British Empire. He went to India, Aden and Gibraltar, before been stationed in the British colony of Bermuda.8 His British army service records reveal that his time in the army was uneventful and that he did not participate in any military actions.

His stay in Bermuda would be a short one. He arrived on January 7, 1914 and he resigned from the army on June 29, 1914.9 His timing could not have been better, for on June 28, 1914, the day before he resigned, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo, Bosnia by Gravilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist. This tragic event was the fuse that ignited the powder keg that was European imperial politics, and led to the start of World War I in August of 1914. Albert Osborne would escape the horror of trench warfare, which would become the enduring symbol of this war, by departing for the United States.

Upon his arrival in the United States he can be found in the company of missionaries. The Washington Post reported that a man named Albert Osborne was one of a group of people who participated in a program that illustrated the life and customs of peoples in India, China and other countries. The presentation took place at the Seventh Day Adventist Washington Missionary College that operated missions in foreign countries.10 As we will see later, other newspapers in later years will also write stories about a man named Albert Osborne who gave lectures about his travels in India, and he was the same man who would go by the name of John Howard Bowen.

In 1917 Osborne did something that cannot be explained. By that year World War I had been raging for three years and had killed millions of soldiers in Europe. But this horror did not stop him from enlisting in the Canadian Army, which had been fighting in Europe since 1914. Upon enlistment, he completed an “Attestation Paper Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force” (Appendix 3).11 This document was an army application form. On it he indicated that he enlisted at Toronto, Canada on August 2, 1917 and that his present address was Nashville, Tennessee.12

A comparison of his British and Canadian army application forms reveals that there are some important discrepancies between the descriptions of the man who enlisted in the British Army in 1906 and the man who joined the Canadian Army in 1917. There is a significant difference in his height, the year of birth is not correct and the middle names are different. These differences may suggest that someone other than Osborne had joined the Canadian army using his identity. A more likely explanation is that these differences can be explained, and that the man known as Albert Osborne who resigned from the British army in 1914 is the same man who joined the Canadian army in 1917.13

The most compelling difference between the two application forms is his height. When he enlisted in the British army in 1906 at the age of 18, his height was 5 feet 4.5 inches.14 When he joined the Canadian army in 1917, his height was 5 feet, 9 inches, a difference of 4.5 inches.15 His British army service records provide a clue that may explain this height difference. It states that “After six months service and gymnastic courses” his height was now 5 feet 5.5 inches; he had grown one inch in six months.16 His increase in height may be explained by his age. As he was only 18 when he enlisted in the British army; he may have been young enough to have not reached his full height, as can be seen by the additional one inch he gained in the six months after his enlistment. Unfortunately, his British army service records do not provide his height when he left the army in 1914 at the age of 25, by which time he must have attained his full height; consequently, it cannot be confirmed if he had added 3.5 inches during his tenure with the British army. Both of his British and Canadian military service records also do not include photographs of him that can be compared to determine if they are the same man.

There are two other discrepancies on his Canadian army application form. He stated that he was born on November 12, 1885; his correct date of birth is November 12, 1888. He also stated that his middle names were Victor and Emmanuel.17 These names are not included on his British army application form or on the “Certified Copy of an Entry of Birth” that provides his date of birth and his name when born.18 Osborne’s name can also be found in the 1891 and 1901 English censuses and the only name provided is Albert.19 These two differences suggest that someone else may have acquired Osborne’s personal information, and in the process of doing so did not did not acquire all of the correct data. This theory could be true if the year of birth had been the only personal information that was not correct because a person using his identity would use the date provided, believing it to be correct. This is not so with his middle names, because Osborne did not have any, and a person who had acquired Osborne’s identity would not have had any reason to state that his middle names were Victor and Emmanuel.

Then why alter his year of birth and add these two middle names to his application form? A possible explanation is that it is an early experiment in altering his identity and may also explain the one-year discrepancy in his age on his British army application form. Eventually he would take on a completely new identity, that of John Howard Bowen, and would continue to alter his identity when he saw fit to do so. For example, on his application for a new Canadian passport dated October 10, 1963, he used his real name Albert Osborne but added the middle name Alexander.20

Osborne’s enlistment in the Canadian army, like his stint in the British army, was uneventful. His army service records reveal that he spent the remainder of the war safely on Canadian soil, and he did not travel to Europe to join the fighting there. He did however become ill. His medical records indicate that he was diagnosed with malaria in June of 1918. He told the doctor treating him that he contracted it in Egypt in 1915 but does not state what he was doing there.21 How did he contract malaria? He may have gone to Egypt as he told the doctor treating him or he may have contracted it in Canada while serving in the army. According to an article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, malaria was brought to Canada by infected European immigrants in the nineteenth century and did not diminish until early in the 20th century.22

Leaving the Military

On January 31, 1919, he was discharged from the Canadian army, and on his “Canadian Expeditionary Force Discharge Certificate” he said that his address on discharge was Nashville, Tennessee.23 According to an FBI interview given on March 3, 1964, Osborne went to Washington D.C. sometime after the war where he met a Syrian whose name he could not remember. The two of them went into the rug cleaning business and traveled throughout the United States cleaning rugs.24 Osborne did not provide any corroborating evidence to support his claim that he both met the unnamed Syrian and went into the rug cleaning business with him. But there is an advertisement in an Indiana, Pennsylvania newspaper that may shed some light on his story. The Indiana Evening Gazette published an advertisement with the title “A Letter from Mr. Osborne” that was signed by “Albert Osborne” (Appendix 4). The advertisement was placed by T.B. Buchholz & Company of Indiana Pennsylvania. The company’s services included rug cleaning for both oriental and domestic rugs.25 Could the Albert Osborne from this advertisement be the same man that also went by the name of Bowen? It is highly doubtful that Osborne would have used this company’s services. As of April 14, 1943, he was in Knoxville, Tennessee, which is over 500 miles from Indiana, Pennsylvania. Osborne may have vouched for this company’s services even though he had not purchased them; acting as a shill would be an activity that a man using false identities might get involved in. He may have also changed his story from the dubious activity of being a shill to the more lawful job of a rug cleaner when he was questioned by the FBI. The other possibility is that there was a man named Albert Osborne who resided in Indiana, Pennsylvania who had used their services.

While it is doubtful that Osborne worked as a rug cleaner, there are numerous newspaper articles that describe a man named Albert Osborne who gave lectures and acted. On November 19, 1924, The Winston Salem Journal reported that a “Dr. Albert Osborne, who has gained much fame as a lecturer on India …” spoke about his travels in India in Leakesville, Virginia. The same article describes him as a son of American missionaries and a graduate of Oxford University in England, which he added to his biography. The article also mentions that he had been on the Chautauqua26 stage for a number of seasons.27 On February 9, 1925, The Charlotte Observer reported on a Dr. Albert Osborne who had lectured about Christianity in India, Africa and Korea. He is again described as the son of missionaries and an Oxford graduate and is described as “… of Washington, D.C. lyceum and Chautauqua lecturer…” 28 Could this be the Albert Osborne that the FBI found on the Mexican bus manifest? He could lecture on India, as he had spent about four years there when he was in the British Army. Adding the title of doctor to his name and lying about his education and his parents is not beyond what he was capable of. This information is also corroborated by his sister, Ada Amos, who told the FBI in 1964 that he was an actor and lecturer on India.29 As we shall see, this is more credible than the rug cleaning story.

On October 9, 1925, The Knoxville News reported that the missionary Albert Osborne would be traveling to India (Appendix 5).30 Ten years later there is another man in Knoxville lecturing on life in India. His name is not Albert Osborne. It is John H. Bowen, who the newspaper describes as the “… Famous Teacher.” The Knoxville-News Sentinel report dated March 28, 1935 also mentioned that he taught in India for 11 years (Appendix 6).31 On April 14, 1935, the same newspaper said that J. H. Bowen, who had been a missionary in India for a few years, had been lecturing in different Knoxville schools about life in India.32 Is the man who is now lecturing about India and who goes by the name of Bowen the same Albert Osborne who departed for India in 1925? The similarities in the stories about India and being famous, which are mentioned in a previous story about him, are hard to ignore. Though one has to wonder if the newspaper reporters who wrote the stories, both of whom worked for the same newspaper, noticed the discrepancy in how much time he told them he spent in India.

Another interesting question about Osborne is how he could depart Knoxville in 1925 and return to the same city using a different identity without being recognized by anybody. The exact date of Osborne’s arrival in Knoxville after his alleged 11 year trip to India is unknown, but newspaper reports indicate that he was back as early as 1934. The Knoxville-News Sentinel dated October 10, 1937 wrote that on October 12, 1934, J. H. Bowen, F. M. Long, former YMCA Secretary for South America, local businessmen and professionals met with young boys and convinced them to join a new organization called the Campfire Council.33 He was also a member of the First Baptist Church in Knoxville by November 1934.34 Assuming that 1934 is the year that he arrived in Knoxville, then how can Osborne the Indian missionary become Bowen the Campfire Council member who also speaks about life in India, nine years later without being recognized by anybody as Albert Osborne? This is difficult to explain and needs to be explored further. One possible explanation lies in the fact that the 1925 article that placed him in Knoxville stated that he spoke there but did not say that he was a long-term resident of that city. A long-term resident would most likely have had associations with enough people to make it difficult to return without being seen by people who knew him as Osborne. This may explain why he was not recognized when he returned there.

Creating the Campfire Council

In 1934, Osborne, using his alias Bowen, became one of the founders of the Campfire Council. The goal of the Campfire Council as stated in its “Charter of Incorporation” of 1938 by the State of Tennessee was “… for the welfare, aid, and benefit of underprivileged boys and girls …” (Appendix 7).35 The Knoxville-News Sentinel story dated October 10, 1937 read, “Such crime prevention work on the part of the Campfire Council attracted the attention of those keenly interested in the reduction of juvenile delinquency.”36

By all accounts, the Campfire Council was a success. On April 23, 1939, The Knoxville News-Sentinel published an article, “Campfire Council Work Gets High Praise From Official and Committee.” This article painted a glowing portrait of how the Council had helped “Well over 800 underprivileged boys spen[d] their leisure time in the gymnasium and playgrounds, operated by this organization.” The boys were able to participate in events such as woodworking, painting, basketball, softball and other activities. The Council also provided, among other things, free lunches and clothing.37 Campfire Council boys were also awarded prizes. James Thompson and Herbert Sams were awarded a prize of a trip to Bermuda because they were “… outstanding members of the organization.” They were accompanied on the trip by Osborne,38 who had visited Bermuda numerous times.39 The article also mentioned the work done by Osborne: “Mr. Bowen’s work has long passed the experimental stage. During these five years, seventeen juvenile gangs have been won over to a constructive program of good citizenship.”40

The Campfire Council’s success was followed by the creation of another organization: Boysville. Boysville was created to provide aid to delinquent boys and a meeting was planned for April 5, 1940 to discuss plans to create it. The newspaper report also stated that it was “… patterned after the Nebraska institution.”41 The Nebraska institution that was referred to was Boystown, which was founded in 1917 by Father Edward Flanagan and whose mission it was to help destitute boys.42

Osborne’s stellar record with the Campfire Council would soon be marred by an accusation made by Charles M. Pickel who lived in the vicinity of Boysville. He said that a boy at the camp had told a man named George Sharp that Osborne, who was known as Bowen at Boysville, had stomped on an American flag. Pickel accused the boys at the camp of thievery and vandalism, and complained about the noise made by the police dogs at the camp.43 The camp at Boysville had an American flag. A newspaper article written by J. H. Bowen, dated July 28, 1940, in The Knoxville News-Sentinel reported that there was a flag raising and lowering ceremony every morning and afternoon at the camp.44 A Tennessee Highway Patrolman investigated these claims at the request of the FBI but could not find any evidence that Bowen had stomped on the flag. The only complaint that local residents had were in regard to the police dogs at the camp, of which they were afraid.45

Osborne’s reputation again came into question in 1943 when he was accused of making sexual advances to some of the boys at the Campfire Council. This time the charges stuck, since he left the Council. His departure was mentioned in the newspaper, but the accusations made against him were not divulged. This omission would allow him to return to Knoxville in the future with his reputation intact.46

In Canada and Announcing his Retirement

For the next few years there are scattered sightings of Albert Osborne. In a letter to the editor in 1946, Osborne, using his alias John Howard Bowen, writes that he attended a banquet in Laredo that was attended by both Protestant and Jewish congregations.47 In 1947 he spoke at the Knoxville Cavalry Baptist Church where he told his audience that he “… was director of religious education for the Baptist Church …” for the last five years,48 even though he had only left his position at the Campfire Council four years previously. In a 1948 letter to the Knoxville News-Sentinel he refers to himself as “Reverend” and describes how Christmas was celebrated in Huajuapan de Leon Oaxaca in Mexico.49

Osborne also traveled to Canada. A document sent by him to the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) in Ottawa, Canada requesting a copy of his military service certificate indicated that he was staying at the YMCA in Toronto.50 The request made by him is not dated, but was answered on June 4, 1953, which suggests that he was in Toronto sometime before June of 1953. The reason for requesting this document is not known, but on November 12, 1953 he would be 65, and he may have been eligible for veteran’s benefits because of his service in the Canadian army during World War I.

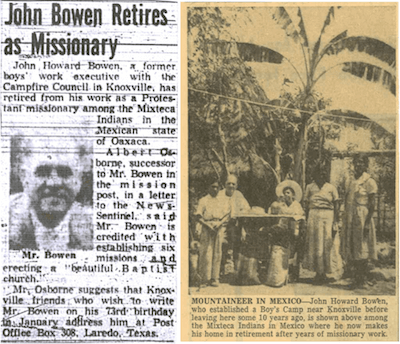

In 1953 Osborne claimed that he retired from missionary work. “Bowen’s” retirement was announced in an article published in The Knoxville News-Sentinel on December 5, 1953.51 The newspaper’s source for this information is a letter it received from Bowen’s successor at the mission. That person’s name is none other than Albert Osborne. Osborne also mentions that Bowen’s 73rd birthday is in January and friends may write to him at Post Office Box 308 Laredo Texas. Why he is now using his real name is not certain, but he must have been confident enough to use his real name without someone in Knoxville making a connection between his real name and his alias, John Howard Bowen.

The Knoxville News-Sentinel was not the only newspaper to publish a story about his retirement. The Knoxville Journal also wrote a story about his retirement and it was published on the same day.52 Comparisons of the two stories reveal that the stories had some similarities and some differences. His successor, Albert Osborne, is not named and the source who told the newspaper that he was retiring is not provided in The Knoxville Journal story. The same Laredo mailing address is provided in both articles, but The Knoxville Journal article invites friends to write to him at Christmas, rather than in January for his birthday. The most important anomaly in the stories lies in the pictures that each newspaper published. The pictures were not the same. The Osborne portrayed in The Knoxville News-Sentinel appears to be heavier and has a receding hairline (Appendix 8). The man portrayed in The Knoxville Journal, is wearing a sun helmet and zippered jacket (Appendix 9). He is slimmer but his hairline cannot be determined because he has a hat on. Patricia Winston and Pamela Mumford, who were allegedly on the same bus as Osborne going to Mexico, were shown the picture in The Knoxville Journal and both could not identify him as John Howard Bowen.53 The pictures may have been taken at different times, which may account for the different appearances. But one has to wonder if Osborne’s friends and associates in Knoxville recognized both men in these two pictures as the man they knew as John Howard Bowen.

Was Osborne Really a Missionary?

Osborne’s retirement from missionary work raises the issue of whether or not he was a real missionary. There are some witnesses that say he was one, but none of them indicated that they actually saw him engaged in this work. In a newspaper report dated September 11, 1954, Claude L. Baker Sr. of Elmo, Tennessee, who knew Osborne as Bowen, stated that Osborne was involved in missionary work in the Mixteca Indian territory in Southern Mexico.54 His statement must be questioned because the article did not say if he met Osborne in Mexico doing missionary work, or if he was told by him that he was involved in it. Reverend Walter Laddie Hluchlan, who knew Osborne as Bowen, said that he gave bible lessons for many years to boys55 who resided at his residence.56 Even though Hluchlan did not say he actually saw him teaching those boys, there could be some truth to his statement. The Osborne who resided in Knoxville spent many years working at the Campfire Council, which catered to young boys. It would not be unusual for him to work with them, so this could be true. Mrs. Virgil Dykes, who was questioned about Bowen by the FBI, told them that she never met him but made contributions to his mission, and did not indicate that she had proof that he was doing missionary work.57 Oddly enough, The Knoxville Journal published a story dated November 28, 1954 in which he said that he had now returned to missionary work. And the story conveniently included a picture of him surrounded by Mixteca Indians (Appendix 10).58 The source for this article is a letter written by Osborne, so the veracity of it must be questioned. The inclusion of the Mixteca Indians could have been an attempt by him to convince his readers that he really was working with them. And the inclusion of his home address can be construed as a way to encourage people in Knoxville to send him money to support his alleged mission. As many who have studied the CIA understand, Allen and John Foster Dulles made extensive use of missionaries and other religious organizations as cover for intelligence agents and operations.59

During their investigation, the FBI confirmed that Osborne had a social security number (SSN) and that the number was 449-36-9745.60 His statement about having a SSN is confirmed by his application to obtain one, dated August 16, 1943, for which he applied using the name John Bowen. As can be seen on his application form, he states that he is unemployed (Appendix 11).61 This concurs with the fact that he lost his job at the Campfire Council in 1943. He also does not know his parents’ names. What is unusual about the application form is the way he spells the name “John”. The way that it is spelled is “Jno”. This spelling matches exactly the way his first name is spelled in the Knoxville City Directory in 1938 (Appendix 12).62

It is interesting to note that in September of 1962 Osborne made a comment about John F. Kennedy’s presidency. He had returned to Knoxville to speak at a rally at the North Glenwood Baptist Church. He told Fred Allen Jr., who was the church’s pastor and who knew him as Bowen, “… that he ‘felt that it is a very dangerous thing for the United States to have a Catholic as president.’”63 He also told Allen that he did not want to stay at his place because he “… ‘didn’t want to risk getting me involved in something.’”64 This statement by Osborne must have aroused Fred Allen’s suspicions about Osborne’s activities, given that he also made comments about Kennedy’s presidency. It is an interesting fact that when the FBI interviewed Allen in 1964 he failed to mention the conversation he had with Osborne in 1962. Instead, he told them that he had received a postcard from him on February 18, 1962.65 His apparent memory lapse is notable because he remembered an innocuous postcard he received from Osborne, but did not recall an actual conversation he had with Osborne, in which he was told that he might be involved in something and had also commented on the danger involved with having a Catholic president. And the purpose of the interview was an inquiry into that president’s death.

Osborne/Bowen, Mexico City, and Oswald

We now come to 1963. In that year, with no visible occupation, Osborne continued his wandering ways. He was still residing in Mexico, but continued to traverse the United States-Mexican border, something he had been doing since 1939.66 It was on one of these trips that the Warren Report said he ended up on the same bus as a man who was either Lee Harvey Oswald or someone impersonating him. Was he on this bus because there was an Oswald impersonator on it, and he therefore would be able to vouch for the impersonator’s presence on the bus?

Lyman Erickson was director of the Christian Servicemen’s Center in San Antonio Texas. This is where Osborne stayed before he died.67 Erickson knew him as Bowen. He said Osborne had told him “… ‘I traveled to Mexico with Lee Harvey Oswald, and I was called in and questioned about it.’” [emphasis added] Erickson did not quote him as saying, “‘I just happened to sit next to Oswald,’ …”68 A statement by Osborne to the FBI, however, contradicts what he told Erickson. FBI agent Bob Gemberling, in an interview with the BBC69 about Albert Osborne, said, “‘He denied he was sitting next to Oswald.’”70 Gemberling also told the BBC that Osborne’s denial about sitting next to Oswald, even though witnesses said they sat together, resulted in the FBI doing an extensive investigation of the man.71 That FBI report is over ninety pages long and features both an index and Table of Contents. (See Commission Exhibit 2195, in Volume 25 of the Warren Commission) It was due to that FBI inquiry that Osborne showed up not just in the Warren Report, but also in many books written about the JFK case. For instance, Osborne is written about by such authors as Jim Marrs in Crossfire, Philip Melanson in Spy Saga, and Anthony Summers in Conspiracy.

The Mexican authorities had disposed of the original and a copy of the passenger list for the Flecha Roja (Red Arrow) bus that Osborne rode in Mexico. Therefore, the FBI used the luggage manifest and immigration records to piece together who was on the bus.72 This is how they found the name of Mr. Bowen. But they could not find Bowen. One problem with finding Bowen/Osborne was that he had tossed out a bundle of tall tales to the people around him on the bus. As the FBI noted in their long report, he told some passengers that he had never been to England, that he was a retired schoolteacher, and that he was working on a book about the Lisbon earthquake.73

In January of 1964, when the FBI finally did catch up with Osborne in Mexico, he gave no clue that it was actually he on the bus. He told FBI agent Clarke Anderson that he was an ordained Baptist minister. He denied there were any English language speaking passengers on the Flecha Roja bus. He said he had not talked to Oswald, nor sat next to him as others said he did. In fact, the man he described as sitting next to him, dark-complected and Hispanic looking, did not fit the description of Oswald. During one of his four FBI interviews he was shown a photo of Oswald. He said he never saw the man before. During that interview, in February of 1964, he denied the FBI had interviewed him in January. (See the FBI report referenced above and Ron Ecker’s online essay, “From Grimsby with Love”.)

It was not until March of 1964, while staying at a YMCA in Nashville, that Osborne finally admitted he used Bowen as an alias. He offered the Bureau the excuse that John Howard Bowen sounded more American to him. Osborne’s lack of steady income, contrasted with his extensive travels, the tall tales he spewed about the Flecha Roja ride, and his use of a dual identity, should have made him a person of interest to the FBI. There is no evidence he was. Nor is there any evidence Osborne was confronted with perjury or obstruction of justice charges in a murder investigation.

The available evidence cannot reliably answer whether Osborne traveled to Mexico with Oswald, or if it was someone impersonating Oswald as part of a conspiracy to assassinate Kennedy. Some evidence indicates he did sit beside Oswald. Pamela Mumford, allegedly on the same bus as Osborne, was shown pictures of Osborne and she confirmed that he was the man sitting next to him.74 Sitting next to someone on a bus however does not make a person a conspirator. This could have been a coincidence. Any person sitting next to Oswald would have been questioned by the FBI and would have been considered a suspect. But Osborne’s statement to Erickson that he traveled there with him and was not just sitting beside him on the bus cannot be ignored. If the conspirators who planned Kennedy’s murder wanted someone to accompany either Oswald or his impersonator, Osborne would have been a good choice because he could explain his presence on the bus by the fact that he frequently traveled between the United States and Mexico. If possible, more research has to be done on the trip to Mexico. Osborne did not explain to Erickson why he traveled there with Oswald, and it still has not been established to an absolute certainty what the trip’s role, if any, was in Kennedy’s assassination.

After he returned from Mexico, Osborne showed up in New Orleans at the Canadian consulate. He gave an address in Montreal as his permanent residence, saying he had been there since 1917 and that he was a Canadian national. He cancelled his previous Canadian passport and took out a new one. What makes this odd is that the previous passport was only four months old.75

With his new, clean passport Osborne was on the move again in November of 1963. The Knoxville Journal reported that Bowen had departed New York for Europe on November 13, 1963. The newspaper stated that the purpose of his trip was a speaking tour of England, Spain, Portugal and Italy.76 The timing of his trip is an interesting coincidence. The man with dual identities, and who was allegedly on the same bus as the president’s alleged assassin, decided to leave the country on November 13th, nine days before Kennedy was assassinated.

After the Assassination

The FBI spoke to Reverend Walter Hluchlan about Osborne’s European speaking tour. He told them that he received an undated letter from him that stated that he had been on a preaching tour of England, Northern France, Spain and North Africa.77 The letter does not exactly match the newspaper report cited above, as Northern France and North Africa replaced Portugal and Italy. The problem with the letter is that the return address is Mexico and not Europe, so there is no European postal stamp to confirm that he had visited any of these four countries. Mrs. Lola Loving, who knew Osborne as both Osborne and Bowen,78 told the FBI that she had received a letter from him in Spain anywhere from a few weeks to two months ago.79 Her interview with the FBI however did not indicate that she showed them a copy of the letter with a Spanish postal stamp on it.80

We know that he was in England because his brother Walter and his sister Mrs. Featherstone confirmed that he had visited them in Grimsby.81 But this is where the truth ends and fiction begins. Walter Osborne told the FBI that his brother flew to Prestwick, Scotland with scientists who were traveling to Iceland to photograph a volcano. But it was not confirmed if Osborne got off the plane in Prestwick or went with them to Iceland.82 According to the FBI he arrived at his sister’s home by train from Prestwick.83 The FBI was able to determine that he arrived at New York City on December 5, 1963 aboard an Icelandic Airlines aircraft that he boarded in Luxembourg, Belgium.84 Flying on Icelandic Airlines suggests that he made a stop in Iceland. It is unlikely, however, that scientists, assuming that there was a group of them that went there to photograph a volcano, would allow him to accompany them on their trip since he did not have a scientific education.85 Osborne probably made up the story about the trip to Iceland and he flew on an Icelandic aircraft to corroborate his story about being there. He most likely said that he met the scientists in Prestwick because he arrived at his sister’s home from a train and this would add credibility to his story. To this day, his trip to Europe after the assassination is shrouded in mystery, and we do not know where he was on November 22, 1963.

For the wandering Osborne, his final destination was a hospital in Texas. He died at the Medical Arts Hospital in San Antonio on August 31, 1966.86 His “Certificate of Death” attributed his passing to a number of problems, one of which was kidney failure. The person who informed the authorities of his passing was Reverend Lyman Erickson. 87 When the FBI found out about his death they told him not to speak about Osborne’s passing. In an interview with the Knoxville News-Sentinel in 1993, Erickson said he was told by the Bureau “… ‘to forget everything I knew about him, told me to forget I ever knew him, and told me to never to speak of this matter to anyone.’”88 Reverend Erickson complied with the FBI request and asked Roy Akers Funeral Chapel in San Antonio, where Osborne’s remains had been sent, “… not to run notices in paper as FBI requested that it be kept quiet as possible.” (Appendix 13).89 Erickson must have also realized that the man who had been staying with him was enigmatic. He told The Knoxville News-Sentinel that the man he knew as John Howard Bowen owned a kit bag that had a false bottom that contained his Albert Osborne identification papers.90 He too was interviewed about Albert Osborne by the BBC and he quite logically said, “‘I think he was an agent. My problem is, I don't know if he was an agent for the United States or a foreign government.’”91

John Howard Bowen

John Howard Bowen was born in Chester Pennsylvania on January 14, 1880.92 His parents were James and Nellie Bowen, and according to the 1900 United States Census, his father was born in 1853 and his mother in 1868.93 The census also indicates that they had two sons, Howard J., born in 1880, and Alfred V., born in 1882.94 Not much is known about his early life except for the fact that his father married after his two sons were born. The Chester Times dated May 11, 1886 announced the wedding of a Mr. James A. Bowen to Mrs. Nellie Gillen, both of Chester, in Camden, New Jersey.95 On Bowen’s application for social security (Appendix 14), he indicated that his mother’s name was Edith Montgomery; therefore, Bowen’s father was married prior to 1886 to another woman who bore the children, and then either died or they were subsequently divorced.

Bowen or his parents had some religious inclinations, as he was baptized on January 21, 1897. A record of baptisms from a United Methodist church shows that his brother Alfred Victor was also baptized on the same day.96 On September 13, 1905, Bowen married Fannie Mae Hall, 97 and their marriage produced no children.

In 1910 Bowen was employed as a printer in Camden, New Jersey.98 In 1910 or 1911 he began a career with the YMCA that would last over 20 years.99 He began work with the YMCA in their railroad Department100 in Camden, New Jersey.101 His job required him to move from time to time, and he lived in: Conemaugh, Pennsylvania; Gassaway, West Virginia; and Hamlet, North Carolina, where he remained until his employment with the YMCA ended in 1933.102

Tragedy struck Bowen in 1934 when his wife of 29 years, Fannie, died after being sick for a long time.103 In 1935 he moved to Tampa, Florida where he was employed as a hotel clerk.104 On July 6, 1937, John Howard Bowen applied for a SSN. The SSN number he was assigned was 239-12-4551, and this number can be seen on his application form (Appendix 14).105 Unlike Osborne, he knew his parents’ names and he included his middle name as well, which Osborne said he did not know.106 On his application for social security he also indicated that he was employed by the First National Institute of Applied Arts in South Bend, Indiana.107 In 1938 Bowen returned to Hamlet and began work as a desk clerk at a hotel.108 It may be just a coincidence, but when Osborne was interviewed by the FBI, he told them that Bowen had worked at a hotel in New Orleans.109 In 1947 he took a financial interest in the hotel by purchasing its stock with investors J. T. Capehart of Hamlet and A. A. Capehart Jr. of Washington.110

John Howard Bowen was also the subject of a newspaper article. A Hamlet, North Carolina newspaper, The News Messenger, published a series of articles called “People at Work” (Appendix 15). The article stated that Bowen worked at the Terminal Hotel,111 and the YMCA, and had been involved with the Hi-Y and Kiwanis Clubs, and had been a Sunday School Superintendent.112 On October 16, 1961, while out for a walk, Bowen was struck by a car. He never fully recovered from the accident and died on January 31, 1962.113

When did Albert Osborne begin using John Howard Bowen’s identity and did they know each other?

Osborne told a number of stories about when he began using Bowen’s name as an alias. He told the FBI that he first used it in 1916.114 He then told a different FBI interviewer that he began using it after World War I, when he went into the rug cleaning business with a Syrian man.115 Ada Amos told the FBI that she sent money to her brother in New York in the 1920s using the name John Howard Bowen.116 We cannot rely on Osborne’s account of when he used Bowen’s identity because of his tendency to lie. If we rely on Ada Amos’ testimony, then we know that sometime in the 1920s he was using the Bowen alias, because she sent him money using that name. But we must also consider the fact that both Osborne and his sister were questioned by the FBI about events that occurred over 40 years ago, and that their memories may have failed them.

There is a newspaper article that places both men in the same place at the same time. The Charlotte Observer dated December 24, 1929 stated that “Dr. Albert B. Osborne of India, spoke Sunday morning at the Methodist church here, while the devotional services (were) conducted by J. H. Bowen, general secretary of the YMCA at Hamlet” (Appendix 16).117 As mentioned above, Dr. Albert Osborne had given lectures about India, and it would not be uncharacteristic of him to add the initial “B” to his name. The real John Howard Bowen was a long time employee of the YMCA and at this time he resided in Hamlet, North Carolina.118 So it appears that at this event both Albert Osborne and John Howard Bowen are present. The newspaper article does not mention that they were associated in any way, only that they were at the same event. Without knowing if they had met before or were associated with each other in some way – for example through a fraternal organization – Osborne may have acquired personal information about Bowen prior to this event. If it was at this event that they first met, and Osborne was able to glean enough information from Bowen to begin using his identity, then this may explain how and when Osborne began using Bowen’s identity.

APPENDICES

1. “Certified Copy of an Entry of Birth”3.

2. British Army application form “Short Service (All Arms)”7.

3. “Attestation Paper, Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force”11.

4. “A Letter from Mr. Osborne”25.

5. “C.H.S. Hi-Ys to Hear Knickerbocker Thursday”30.

6. “Sequohay Children Hear About India”31.

7. Campfire Council “Charter of Incorporation”35.

8. “John Bowen Retires as Missionary”51.

9. “Bowen Retires After Years As Missionary”52.

10. Bowen with Mixteca Indians58.

11. Osborne application for a social security account number using his Bowen alias 61.

12. 1938 Knoxville City Directory62.

13. FBI request to keep Osborne’s death quiet89.

14. Bowen’s application for a social security account number105.

16. “Dr. A.B. Osborne is Heard at Aberdeen”117.

NOTES

1 The FBI investigation into the life of Albert Osborne can be found in the Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195.

2 Vincent Bugliosi, Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2007) 751.

3 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

4 Ancestry.com. 1891 and 1901 England Census, online database, Provo, Utah.

5 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 41.

6 His British army application form states that Osborne’s age was 19 years I month when he enlisted. His correct age was 18 years 1 month as indicated on his “Certified Copy of an Entry of Birth” (Appendix 2).

7 Ancestry.com, British Army World War One Pension Records 1914-1920 for Albert Osborne, online database, Provo, Utah.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 “Picture Life in Far East,” The Washington Post, November 29, 1914.

11 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

12 Ibid.

13 A copy of Osborne’s Canadian army application form and service records can be downloaded from Library and Archives Canada’s website.

14 Ancestry.com, British Army World War One Pension Records 1914-1920 for Albert Osborne, online database, Provo, Utah.

15 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

16 Ancestry.com, British Army World War One Pension Records 1914-1920 for Albert Osborne, online database, Provo, Utah.

17 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

18 Ibid.

19 Ancestry.com. 1891 and 1901 England Census, online database, Provo, Utah.

20 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 16.

21 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

22 “The return to swamp fever: malaria in Canadians,” J. Dick MacLean, MD and Brian J. Ward MD. Canadian Medical Association Journal, January 26, 1999, CMAJ 1999; 160: 211-2.

23 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

24 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 41.

25 “A Letter from Mr. Osborne,” Indiana Evening Gazette, April 24, 1943.

26 The Chautauqua Institution as it is now called was founded in 1874 in western New York by Methodists who wanted “… to extend the intellectual and critical capacities …” of Christians. Charlotte M. Canning, The Most American Thing in America: Circuit Chautauqua as Performance (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2005) 6. Beginning in 1904, “Circuit Chautauquas” began delivering lectures, musical groups and other programs mainly to rural areas in the United States. Ibid., 1. Plays were added to their repertoire and after 1913 they were a regular part of the Chautauqua experience. Ibid., 14.

27 “Dr. Osborne is Heard on India,” The Winston Salem Journal, November 19, 1924.

28 “Remarkable Lecture at Chadwick Baptist Church,” The Charlotte Observer, February 9, 1925.

29 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 37-38.

30 “C.H.S. Hi-Ys to Hear Knickerbocker Thursday,” The Knoxville News, October 9, 1925.

31 “Sequohay Children Hear About India,” The Knoxville-News Sentinel, March 28, 1935.

32 “What a Place for Housewives – Hindu Women Throw ‘Dishes’ Away After Meal,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 14, 1935.

33 “Organization for Underprivileged Boys From Knoxville’s Street,” The Knoxville-News Sentinel, October 10, 1937.

34 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man,” The Knoxville-News Sentinel, Final Edition, November 28, 1993.

35 State of Tennessee, “Charter of Incorporation”, Campfire Council Incorporated, April 12, 1938.

36 “Organization for Underprivileged Boys From Knoxville’s Street,” op. cit.

37 “Campfire Council Work Gets High Praise From Official and Committee,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 23, 1939.

38 “Campfire Council Boys Felt as If Bermuda Were Home – They Were Greeted by Boys’ Church Brigade,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, August 20, 1939.

39 The Knoxville News-Sentinel reported that Bowen had made 14 trips to Bermuda. The current one, in which he accompanied two Campfire Council Boys, was financed by a local businessmen’s association. The reason for the previous trips are not explained but were financed by people described as friends. “Campfire Chief To Make 14th Bermuda Trip,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, August 5, 1939.

40 “Campfire Council Work Gets High Praise From Official and Committee.”

41 “Boys’ Home Plan Will Be Discussed,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, April 4, 1940.

42http://www.boystown.org/about/father-flanagan/Pages/default.aspx

43 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 6.

44 J.H. Bowen, “Vesper Services and Raising of Flag Observed by Campers,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, July 28, 1940.

45 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 6.

46 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man.”

47 John Howard Bowen, Letter to the Editor Letter Box, The Laredo Times, February 17, 1946.

48 “Religious Director To Tell of Travels,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, May 3, 1947.

49 “Former Knox Minister Describes ‘Posadas,’ Which Mark Christmas Season in Mexico,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, December 25, 1948.

50 Library and Archives Canada, Canadian Expeditionary Force, RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 7492 - 41.

51 “John Bowen Retires as Missionary,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, December 5, 1953.

52 “Bowen Retires After Years As Missionary,” The Knoxville Journal, December 5, 1953.

53 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 10.

54 “Wants Southern Cooking in Libya,” The Knoxville News-Sentinel, September 11, 1954.

55 The following story has more information about Osborne’s life and his work with young boys: “From Grimsby with Love: The Travels of ‘the Reverend’ Albert Alexander Osborne,” Ronald L. Ecker, 2005, http://www.ronaldecker.com/osborne.html.

56 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 57-58.

57 Ibid, 53.

58 Pat Fields, “Once Boys’ Club Backer Missionary In Mexico,” The Knoxville Journal, November 28, 1954.

59 See George Michael Evica’s, A Certain Arrogance, 85 -154.

60 Warren Commission Hearings , Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 22.

61 John Bowen, “Application For Social Security Account Number,” August 16, 1943.

62 Knoxville City Directory, City Directory Company of Knoxville, 1938.

63 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man.”

64 Ibid.

65 Warren Commission, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 64.

66 Ibid, 42.

67 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man.”

68 Ibid.

69 The link for this interview can be found at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/insideout/yorkslincs/series2/kennedy_conspiracy/index.shtml.

70 Interview with Bob Gemberling, Photo Report BBC Inside Out: Kennedy – The Grimsby Connection, 2003.

71 Ibid.

72 James Di Eugenio, Reclaiming Parkland: Tom Hanks, Vincent Bugliosi, and the JFK Assassination in the New Hollywood (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2016) 282.

73 Ibid., 283.

74 Warren Commission, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, pg. 40.

75 John Armstrong, Harvey and Lee: How the CIA Framed Oswald (Arlington Texas: Quasar Ltd., 2003) 619.

76 “Bowen Leaves for Overseas,” The Knoxville Journal, November 14, 1963.

77 Warren Commission, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 34.

78 Ibid., 54.

79 Ibid.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid., 35-36.

82 Ibid. 36.

83 Ibid.

84 Ibid., 43.

85 His sister Ada Amos told investigators that he did not have any scientific credentials. Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 38. Osborne told the FBI that he had left school after the eighth grade. Ibid., 41.

86 Albert Osborne, State of Texas, “Certificate of Death,” State File No. 49975, August 31, 1966.

87 Ibid.

88 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man.”

8989 Letter from Robert Massey to Jim Balloch, post office marked March 1, 1993, The Harold Weisberg Collection, Digital Archive, Hood College, Weisberg Subject Index Files, O Disk, Osborne Albert, Item10.

90 Jim Balloch, “JFK: Trail led to Knoxville man.”

91 Interview with Reverend Erickkson [sic], Photo Report BBC Inside Out: Kennedy – The Grimsby Connection, 2003.

92 Ancestry.com, U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, online database, Provo, Utah.

93 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, online database, Provo, Utah.

94 Ibid.

95 “Married,” Chester Times, May 11, 1886.

96 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, Church and Town records, 1708-1985, online database, Provo, Utah.

97 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, Marriages, 1852-1968, online database, Lehi, Utah.

98 Family Search, United States Census, 1910.

99 Bowen’s employment status with the YMCA for the period 1910 to 1933 can be found in the YMCA’s Yearbooks that were published on an annual basis. The YMCA Yearbooks are located at the University of Minnesota’s Kautz Family YMCA Archives, https://www.lib.umn.edu/ymca.

100 The YMCA’s Railroad Department was created in 1877. It offered railroad workers services such as: bible classes, reading rooms and places to exercise. The goal of this department was to reduce industrial unrest by teaching them Christian values. Nina Mjagkij and Margaret Ann Spratt eds., Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and the YWCA in the City (New York: New York University Press, 1997) 65-66.

101 YMCA’s Yearbooks https://www.lib.umn.edu/ymca.

102 Ibid.

103 “Mrs. J. H. Bowen,” The Charlotte Observer, March 24, 1934.

104 Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, online database, Provo, Utah.

105 John Howard Bowen, “Application For Social Security Account Number,” July 6, 1937.

106 Ibid.

107 Ibid.

108 “People at Work,” The News-Messenger, Hamlet, North Carolina, February 11, 1958.

109 Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 11.

110 “Eure Charters 14 New Firms,” Greensboro Daily News, September 11, 1947.

111 In 1990 the Terminal Hotel was used to film scenes from the movie Billy Bathgate starring Dustin Hoffman. Mike Quick, “‘Billy Bathgate’ Created A New Set Of Memories,” Park Newspapers of Rockingham, North Carolina, May 2, 1993. In 1993 the hotel was destroyed by fire. “Terminal Hotel: A Collection of Memories,” Park Newspapers of Rockingham, North Carolina, May 2, 1993.

112 “People at Work,” The News-Messenger. In 1925 the Cavalry Baptist Church in Kokomo, Indiana, which is about 130 miles from Gary, Indiana where Osborne’s sister Ada Amos lived (Warren Commission Hearings, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 37), had a Sunday School Superintendent named Albert Osborne. “Sunday Services in the Churches,” The Kokomo Daily Tribune, December 12, 1925.

113 “John H. Bowen Dies at Hamlet,” The News-Messenger, Hamlet, North Carolina, February 2, 1962.

114 Warren Commission, Volume 25, Commission Exhibit 2195, 43.

115 Ibid., 41.

116 Ibid., 38.

117 “Dr. A. B. Osborne is Heard at Aberdeen,” The Charlotte Observer, December 24, 1929.

118 Year Book and Official Rosters of the National Councils of the Young Men's Christian Associations of Canada and the United States of America, 1928-1929,95 and 1929-1930, 39.