51. The Credibility Of Shells?

Commission Conclusion – “The three used cartridge cases found near the window on the sixth floor at the southeast corner of the building were fired from the same rifle which fired the above-described bullet and fragments, to the exclusion of all other weapons.”

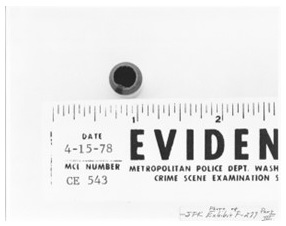

The case assembled against Oswald, stands primarily on the shaky pillars of circumstantial evidence. Paramount among this evidence are three shell casings, designated as CE543, 544, and 545. These were purportedly found on the sixth floor in the aftermath of the assassination. However, the procurement of this evidence revels a labyrinth of inconsistencies concerning the management and preservation of this so-called evidence.

Scrutinising the chain of custody for these exhibits reveals a disconcerting pattern of discrepancies, starting from their alleged discovery. A glaring contradiction is discernible between the timing of the shell casings discovery as per the Warren Commission's Report, and the account provided by Deputy Sheriff Luke Mooney. The Commission's suggests a twelve-minute lapse between the discovery of the supposed "Sniper's Nest" and the spent cartridges, a fact that starkly contrasts with Mooney's first-hand testimony.

Deepening the sense of impropriety are the baffling irregularities in the treatment of the shell casings. As per Lt. J. C. Day's testimony, the shell casings were not duly marked at the crime scene, a blatant violation of the standard protocol essential for preserving the sanctity of evidence. Furthermore, the casings were housed in an unsealed envelope, opening Pandora's box of potential contamination threats and casting a dark cloud over the integrity of the evidence. The uncertainty is further amplified when a cornerstone piece of evidence, Commission Exhibit 543, falls prey to misidentification, consequently pushing the case's credibility into further tumult.

David Belin. “All right. Let me first hand you what has been marked as ‘Commission Exhibit,’ part of ‘Commission Exhibit 543, 544,’ and ask you to state if you know what that is.”

Lt Carl Day. “This is the envelope the shells were placed in.”

David Belin. “How many shells were placed in that envelope?”

Lt Carl Day. “Three.”

David Belin. “It says here that, it is written on here, "Two of the three spent hulls under window on sixth floor."

Lt Carl Day. “Yes, sir.”

David Belin. “Did you put all three there?”

Lt Carl Day. “Three were in there when they were turned over to Detective Sims at that time. The only writing on it was "Lieut. J. C. Day." Down here at the bottom.”

David Belin. “I see.”

Lt Carl Day. "Dallas Police Department and the date.”

David Belin. “In other words, you didn't put the writing in that says Two of the three spent hulls."

Lt Carl Day. “Not then. About 10 o'clock in the evening this envelope came back to me with two hulls in it. I say it came to me, it was in a group of stuff, a group of evidence, we were getting ready to release to the FBI. I don't know who brought them back. Vince Drain, FBI, was present with the stuff, the first I noticed it. At that time there were two hulls inside. I was advised the homicide division was retaining the third for their use. At that time, I marked the two hulls inside of this, still inside this envelope.”

David Belin. “That envelope, which is a part of Commission Exhibits 543 and 544?”

Lt Carl Day. “Yes, sir; I put the additional marking on at that time.”

David Belin. “I see.”

Lt Carl Day. “You will notice there is a little difference in the ink writing.”

David Belin. “But all of the writing there is yours?”

Lt Carl Day. “Yes, sir.”

David Belin. “Now, at what time did you put any initials, if you did put any such initials, on the hull itself?”

Lt Carl Day. “At about 10 o'clock when I noticed it back in the identification bureau in this envelope.”

David Belin. “Had the envelope been opened yet or not?”

Lt Carl Day. “Yes, sir; it had been opened.”

David Belin. “Had the shells been out of your possession then?”

Lt Carl Day. “Mr. Sims had the shells from the time they were moved from the building, or he took them from me at that time, and the shells I did not see again until around 10 o'clock.”

David Belin. “Who gave them to you at 10 o'clock?”

Lt Carl Day. “They were in this group of evidence being collected to turn over to the FBI. I don't know who brought them back.”

David Belin. “Was the envelope sealed?”

Lt Carl Day. “No, sir.”

David Belin. “Had it been sealed when you gave it to Mr. Sims?”

Lt Carl Day. “No, sir; no.”

David Belin. “Your testimony now is that you did not mark any of the hulls at the scene?”

Lt Carl Day. “Those three; no, sir.” (Volume IV, p. 253-255)

The following affidavit was executed by J. W. Fritz on June 9, 1964.

The Spent Rifle Hulls

Three spent rifle hulls were found under the window in the southeast corner of the 6th floor of the Texas School Book Depository Building, Dallas, Texas, on the afternoon of November 22, 1963. When the officers called me to this window, I asked them not to move the shells nor touch them until Lt. Day of the Dallas Police Department could make pictures of the hulls showing where they fell after being ejected from the rifle. After the pictures were made, Detective R. M. Sims of the Homicide Bureau, who was assisting in the search of building, brought the three empty hulls to my office.” (Volume VII; p. 403)

However, the narrative provided by Fritz sharply diverges from the recollection of Tom Alyea, a cameraman for WFFA TV. Alyea provides a contrasting perspective on the actions taken by the Dallas Police on the sixth floor following the assassination.

Tom Alyea. “After filming the casings with my wide-angle lens, from a height of 4 and half ft., I asked Captain Fritz, who was standing at my side, if I could go behind the barricade and get a close-up shot of the casings.

He told me that it would be better if I got my shots from outside the barricade. He then rounded the pile of boxes and entered the enclosure. This was the first time anybody walked between the barricade and the windows. Fritz then walked to the casings, picked them up and held them in his hand over the top of the barricade for me to get a close-up shot of the evidence. I filmed between 3–4 seconds of a close-up shot of the shell casings in Captain Fritz's hand. Fritz did not return them to the floor, and he did not have them in his hand when he was examining the shooting support boxes. I stopped filming and thanked him. I have been asked many times if I thought it was peculiar that the Captain of Homicide picked up evidence with his hands. Actually, that was the first thought that came to me when he did it, but I rationalized that he was the homicide expert, and no prints could be taken from spent shell casings. Over thirty minutes later, after the rifle was discovered and the crime lab arrived, Capt. Fritz reached into his pocket and handed the casings to Det. Studebaker to include in the photographs he would take of the sniper's nest crime scene. We stayed at the rifle site to watch Lt. Day dust the rifle. You have seen my footage of this. Studebaker never saw the original placement of the casings, so he tossed them on the floor and photographed them. Therefore, any photograph of shell casings taken after this is staged and not correct.” Follow this link.

Tom Alyea further claimed, in correspondence with Tom Samoluk of the ARRB, that Day and Studebaker committed perjury in testifying to the Warren Commission.

“Regarding the perjured testimony given to the Warren Commission Investigators by members of the Dallas Police Department. I understand there were several cases, but the one I checked for myself by reading the printed testimony in the Warren Report, involves Lt. Day and Det. Studebaker. These are the two crime lab men who dusted the evidence on the 6th floor. Their testimony is false from beginning to end. I suggest their reason was to protect their boss, Captain Fritz, and perhaps their own pensions.” Follow this link.

Appraisal Of The Known Facts. The handling, preservation, and chain of custody of Commission Exhibits 543, 544, and 545, are encrusted within a myriad of inconsistencies and procedural aberrations. Such discrepancies not only lay bare the potential for contamination, misidentification, and improper handling of evidence but it also invites profound scepticism about the evidence's trustworthiness, and by extension, the solidity of the case against Oswald. Remember in all criminal proceedings the onus is on the prosecution to present undeniable proof of guilt and like in all the evidentrary aspects of the case against Oswald, this burden is seriously flawed.

52. No Package In Oswald’s Hands.

Commission Conclusion: “Oswald carried his rifle into the Depository Building on the morning of November 22, 1963.” (WCR; p. 19)

Oswald was seen entering the Texas School Book Depository on the morning of 11/22/63 by “one employee, Jack Dougherty, [who] believed that he saw Oswald coming to work but does not remember “that Oswald had anything in his hands as he entered the door” (WCR; p. 133).

Dougherty's testimony in the record.

Joseph Ball. “Now, is that a very definite impression that you saw him that morning when he came to work?”

Jack Dougherty. “Well, oh--it's like this--I'll try to explain it to you this way--- you see, I was sitting on the wrapping table and when he came in the door, I just caught him out of the corner of my eye---that's the reason why I said it that way.”

Joseph Ball. “Did he come in with anybody?”

Jack Dougherty. “No.” Joseph Ball. “He was alone?”

Jack Dougherty. “Yes; he was alone.”

Joseph Ball. “Do you recall him having anything in his hand?”

Jack Dougherty. “Well, I didn't see anything, if he did.”

Joseph Ball. “Did you pay enough attention to him, you think, that you would remember whether he did or didn't?”

Jack Dougherty. “Well, I believe I can---yes, sir---I'll put it this way; I didn't see anything in his hands at the time.”

Joseph Ball. “In other words, your memory is definite on that is it?”

Jack Dougherty. “Yes, sir.” (Volume VI; p. 376/377)

This discrepancy alone would have garnered significant consequences for Wade's case against Oswald. If Oswald did not carry a rifle into the building on 11/22/63 as Dougherty's testimony suggests, then a critical piece of the prosecution's case is seriously undermined. This alone might be enough to introduce reasonable doubt into the case against Oswald.

53. The Phantom Paper Sack.

“If there is no gun-sack, there is no gun”. Jim DiEugenio.

Commission Conclusion. “The improvised paper bag [CE142] in which Oswald brought the rifle to the Depository was found close by the window from which the shots were fired.” (WCR; p.19) (Reclaiming Parkland; p. 187)

Evidence In The Record Which Refutes The Commission Conclusion.

1. Primarily, there exists no photographic evidence validating the presence of CE142 on the sixth-floor post-assassination. This lack of visual evidence casts significant doubt upon the very existence of CE142. According to the Warren Report, Captain Fritz had expressly commanded that no object should be disturbed or relocated until law enforcement forensics could meticulously record the crime scene using photographic and fingerprint methods. If these directives were adhered to as stated, it raises a compelling question: Why is there an absence of photographic evidence concerning CE142. (WCR; p. 79)

2. Commission Conclusion. “[Oswald] left the bag alongside the window from which the shots were fired”. (WCR; p.137)

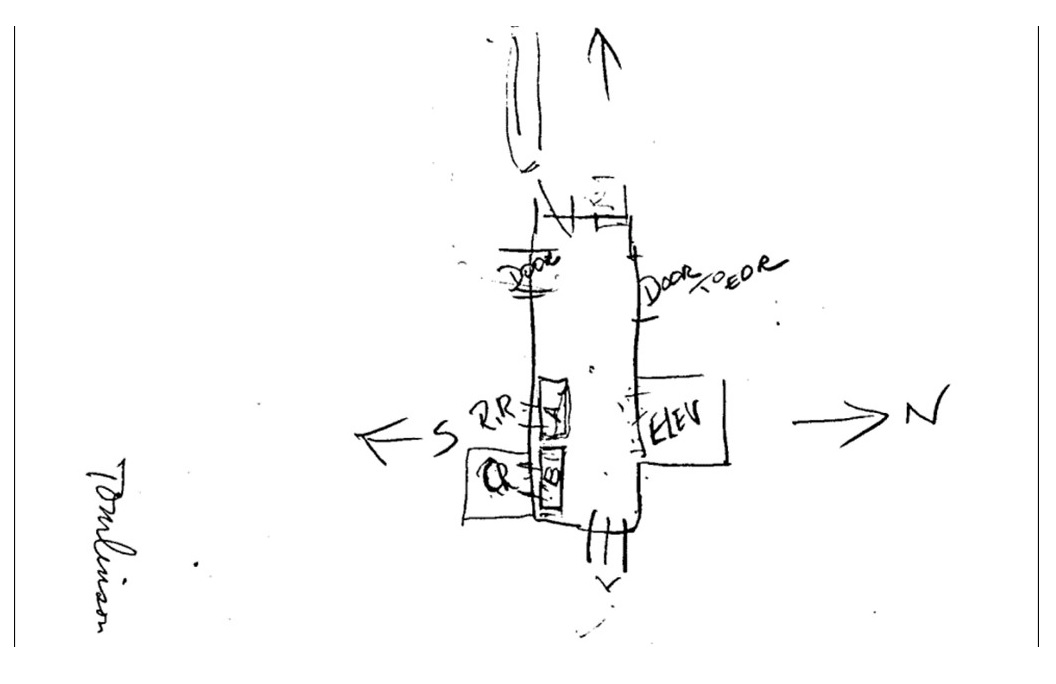

CE1302 “Approximate Location Of Wrapping Paper Bag. (WCR; p. 139)

The absence of a photograph which confirms the presence of CE142 around the crime scene is conspicuously evident. Instead, the Commission resorted to publishing a simulated image within their volumes, labelled as CE1302. This image features a dotted line representing the purported location of the paper sack. Detective Robert Studebaker testified that the FBI requested him to superimpose this line onto a crime scene photograph to indicate an approximate location where the bag was allegedly discovered. The veracity of this image is thus open to severe doubt.

Given that it's a reconstructed portrayal rather than an original photograph of the crime scene featuring CE142, its evidentiary weight is non-existent.

This dialogue between counsel Joseph Ball and Detective Studebaker illuminates this questionable practice:

Joseph Ball. “Do you recognize the diagram?”

Robert Studebaker. “Yes, sir.”

Joseph Ball. “Did you draw the diagram?”

Robert Studebaker. “I drew a diagram in there for the FBI. Someone from the FBI — I can't recall his name at the moment — called me down. He wanted an approximate location of where the paper was found.” (Volume VII; p. 144)

This admission uncovers the lack of tangible evidence and reliance on fabricated illustrations, further undermining faith in the Commission's conclusions. It provokes questions regarding the investigation process's transparency and authenticity, casting serious doubt on the Commissions case against Oswald. The lack of an authentic photograph, surreptitiously replaced by a manipulated image, signals serious flaws in the handling of this pivotal evidence no doubt further eroding the confidence of the prosecution’s case against Lee Oswald.

Commission Conclusion.” [Oswald] Took paper and tape from the wrapping bench of the Depository and fashioned a bag large enough to carry the dissembled rifle. (WCR; p.137)

3. There is no eyewitness testimony in the record which can collaborate the commissions conclusions regarding the origin of CE142. Troy West's testimony is pivotal in this context. As an employee who dispensed the packing materials—paper, tape, and string—he maintained that he remained at his first-floor workstation throughout the days leading up to the Presidents assassination and even during the motorcade. West, who recognized Oswald, firmly stated he had never seen Oswald attempting to construct a bag, prior to or on the day of the assassination.

When questioned by staff lawyer David Belin about whether Oswald had ever been seen around the wrapping materials or machinery, West responded, "No, sir; I never noticed him being around." This testimony was underscored by the late Ian Griggs, a British police investigator. Griggs pointed out two intriguing aspects: firstly, West expounded on the impossibility of removing tape from the dispenser, which was incorporated into a machine that moistened the tape as it was dispensed. Secondly, the FBI later claimed that the tape on the sack bore the specific markings of this machinery. (No Case to Answer, p. 204)

During West’s testimony, Belin asked several pointed questions: "Did Lee Harvey Oswald ever help you wrap mail?" To which West responded, "No, sir; he never did." Belin pressed further, "Do you know whether or not he ever borrowed or used any wrapping paper for himself?" West replied simply, "No, sir. I don't." (Volume VI; p. 356–363)

As Belin's questions continued to draw a blank, this only reinforced the contention that Oswald had no interaction with the wrapping materials or machinery. This contradicts the Commission's assertion that Oswald had manufactured the bag using the Depository's materials. Furthermore, the Commission's conclusion doesn't address this illogical inconsistency: why would Oswald create a paper bag that could only accommodate a disassembled rifle? If Oswald indeed crafted this bag from scratch, any comprehensive investigation would question why he didn't make it sizeable enough to transport the rifle in its fully assembled state?

4. Commission Conclusion. “The presence of the bag in this corner is cogent evidence that it was used as the container for the rifle. (WCR; p. 135.)

The Commission's conclusion that the bag was used as a container for the rifle forms a crucial part of their case against Lee Oswald. However, this assumption is called into question by expert testimony that is present in the record.

Special Agent James Cadigan, who conducted an examination of the bag for the FBI, presented starkly contrasting findings. According to Cadigan's testimony,

Melvin Eisenberg – “Mr. Cadigan, did you notice when you looked at the bag whether there were---that is the bag found on the sixth floor, Exhibit 142--whether it had any bulges or unusual creases?”

James Cadigan – “I was also requested at that time to examine the bag to determine if there were any significant markings or scratches or abrasions or anything by which it could be associated with the rifle, Commission Exhibit 139 [Mannlicher-Carcano], that is, could I find any markings that I could tie to that rifle?”

Melvin Eisenberg – “Yes.”

James Cadigan – “And I couldn't find any such markings.” (Volume IV; p. 97)

This testimony from a qualified expert undermines the Commission's claim that the bag can be linked definitively to the rifle.

Considering these testimonial inconsistencies, it becomes evident that the Commission's assertion relies heavily on the mere presence of the bag, without substantiating physical evidence to support its intended use. 5. In a correspondence this researcher had with Buell Wesley Frazier in April of 2021, I asked Mr. Frazier:

Johnny Cairns. ”On 11/21/63 prior to, during or after you gave Lee Oswald a ride back to Irving, did you observe at any time Lee with a brown paper bag? Or materials to construct a brown paper bag?”

Buell Wesley Frazier. “No I did not.” (Personal Correspondence)

6. Inconsistencies in the witness testimony regarding the bag add another layer of uncertainty. When witness accounts vary or contradict one another, it becomes challenging to establish a clear and coherent narrative supporting the bag's significance as evidence. (No Case To Answer, p.173-214)

7. Oswald's partial prints.

Commission Conclusion. “Oswald's fingerprint and palmprint found on bag “(WCR; p. 135)

The inception of CE142 and Oswald's ‘handling ‘of it raise further troubling questions. It is important to note that the partial prints on the bag, even if genuine, do not provide conclusive evidence that Oswald constructed the bag or carried it on the day of the assassination. These prints alone are insufficient to establish Oswald's guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Furthermore, the evidence presented in my previous points cast serious aspersions on the CE142 and raises serious doubts about its relevance to the assassination of President Kennedy. This further undermines the significance of the partial prints found on the bag.

In light of these considerations, it is essential to exercise caution when drawing conclusions solely based on the presence of partial prints on CE142. The partial prints alone do not provide definitive evidence of Oswald's involvement in the construction or use of the bag on the day of the assassination.

8. The Greasy-less Prints? “The firing pin and spring of this weapon are well oiled. No oil has been applied to this weapon by the FBI. Numerous shots have been fired with the weapon in its present well-oiled condition as shown by the presence of residues on the interior surfaces of the bolt and on the firing pin.” (Volume XXVI; p. 455.)

The Warren Commission's assertion of Oswald's guilt necessitates the assumption that he engaged in the assembly of the well-oiled Carcano. However, that assumption raises serious doubts with regards to the evidence in this case. For example, the complete lack of any oil or grease residue on Oswald's hands, the lack of visible oil transfer, from the Carcano, onto the surrounding objects within the ‘snipers nest’, the condition of the wooden floor, devoid of any oil stains and the inexplicable absence of Oswald's greasy, oily fingerprints make the Commissions assertions highly improbable. What is the likelihood that Oswald in handling the lubricated components of the Carcano, neglected to leave behind any greasy, oily fingerprints at the crime scene?

The extensive manipulation and shifting through of the rifles various components, within a confined space further intensity’s the scepticism surrounding the absence of any oil transfer from the Carcano to Oswald. Assembling the Carcano in such close quarters would have undoubtedly made it extremely difficult for Oswald to handle it without unintentionally coming into contact with its well-oiled parts.

Also, the absence of any oil on the wooden floor in the vicinity of Oswald's alleged assembly and handling of the Carcano is a significant conundrum. With the rifle, well-oiled, it is reasonable to assume that some oil would have dripped or splattered onto the wooden floor during the assembly. Especially, when it is assumed, Oswald emptied the contents of the ‘paper sack’ onto the floor to assemble the Carcano. The absence of visible oil stains or residue on the wooden floor adds another layer of doubt regarding the purported sequence of events. Wooden floors have a porous nature that would likely absorb or retain oil, making it difficult for oil stains to go unnoticed.

Had Oswald been given the opportunity to stand trial, it would have been a formidable task for Henry Wade, to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that he had assembled the Carcano on November 22, 1963. The rational deductions outlined above cast reasonable doubt on the case against Oswald.

54. Accessories After The Fact. The Palm Print Evidence.

“Few people would be ready to convict a man of murder on the basis of such incomplete investigation or such a dishonest presentation of ‘evidence’. Those who would not send a living man to his death on such a basis must ask themselves whether Oswald should be assigned to history stigmatized as an assassin on grounds that would be inadequate if he were still alive.” Sylvia Meagher.

Commission Conclusion. “Oswald’s palmprint was on the rifle in a position which shows he handled it while it was disassembled.” (WCR; p. 129.) (Accessories After The Fact; p. 120.)

1. There are no existing photographs taken at the time of the investigation that clearly show the presence of the palm print on the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, which is a crucial piece of alleged evidence tying Oswald to the weapon."

The absence of contemporaneous photographs cannot be understated. These photos would have served as a critical piece of forensic evidence, capturing the initial state of the palm print on the weapon. Their absence raises questions about the authenticity and handling of this key evidence.

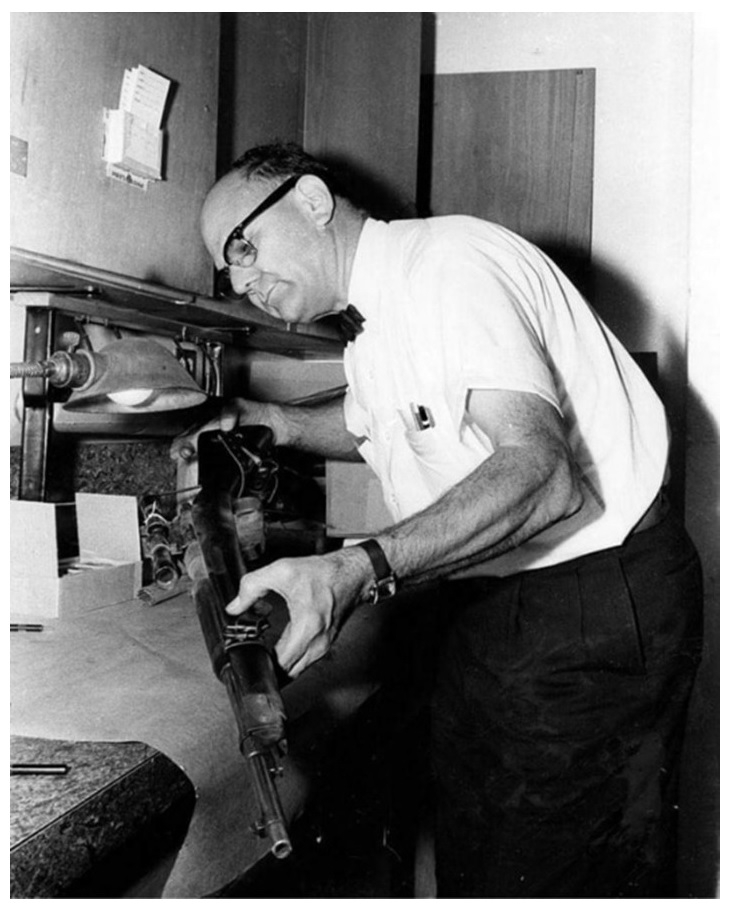

2. “The print on the gun still remained on there... there were traces of ridges still on the gun barrel.” (J.C. Day, Dallas Police)

Contrary to Day's account, FBI Fingerprint Expert Sebastian Latona testified that he couldn't develop any prints on the weapon. “I was not successful in developing any prints at all on the weapon.” (Sebastian Letona, FBI, Volume. IV, p. 23)

Paul Stombaugh of the FBI observed that the gun had been dusted for latent fingerprints prior to his receiving it, with powder visible all over the gun.

“I noticed immediately upon receiving the gun that this gun had been dusted for latent fingerprints prior to my receiving it. Latent fingerprints powder was all over the gun.” (Accessories After The Fact; p.121)

Sylvia Meagher, in her book, questioned the discrepancy between the survival of the dusting powder during the gun's transit from Dallas to Washington, and the complete disappearance of traces of powder and dry ridges claimed to be present around the palm print on the gun barrel.

“How could powder survive on the gun from Dallas to Washington, but every single trace of powder and the dry ridges which were present around the palm print on the gun barrel under the stock vanish?” (Accessories After The Fact; p.122)

3. “Lt. DAY stated he had no assistance when working with the prints on the rifle, and he and he alone did the examination and the lifting of the palm print from the underside of the barrel of the rifle which had been found on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository on November 22, 1963.” (Volume XXV; p. 832.)

4. Even the Commission harboured significant doubts about the belated discovery of the palm print on the rifle. A memorandum from the FBI, dated August 26, 1964, addressing this uncertainty, states:

“There was a serious question in the minds of the Commission as to whether or not the palm impression which had been obtained by the Dallas Police Department is a legitimate latent palm impression removed from the rifle barrel or whether it was obtained from some other source and for this reason this matter needs to be resolved.” Follow this link.

“Go No Further With The Processing”

Partial prints discovered on the exterior of the rifle were photographed by Lt Day. However, the FBI determined that these prints held no evidentiary value. According to Day, he captured these photographs at approximately 8 p.m. on November 22, 1963.

Day testified that he neglected to photograph ‘Oswalds’ latent palm print due to explicit instructions he received from Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry, who ordered him to cease further processing the Carcano. However, during an interview with the FBI, Day stated that he received these orders from Curry shortly before midnight. Therefore, based on his own admission, Day had nearly four hours between taking the photographs of the external prints and receiving the orders from Curry.

Given the potential significance of the latent print as critical evidence in Oswald's trial, it raises the question of why Day chose not to photograph it. It seems likely that he was aware of its importance, making his decision all the more perplexing.

(Accessories After The Fact; p.122) Follow this link.

5. On November 22, 1963, Day reportedly informed Chief Curry and Captain Fritz about the discovery of a palm print on the rifle believed to have been used in the assassination of President Kennedy. Day tentatively identified the palm print as belonging to the primary suspect, Lee Oswald. (Meagher, p. 124)

On November 23rd, when Fritz was asked about the presence of Oswald's prints on the rifle, he responded with a denial, “No sir”. Similarly, Curry also did not reveal publicly this significant discovery. It was not until November 24th, after Oswald was slain that DA Henry Wade, nonchalantly announced the existence of a palm print found on the rifle.

Reporter. “What other evidence chief?”

Henry Wade. “Let’s see, uh. his fingerprints were found on the gun. I said that on the.”

Reporter. “Which gun?”

Henry Wade. “The rifle.”

Reporter. “The rifle fingerprints were his? Oswald’s?”

Henry Wade. “Yes. A palm print rather than a fingerprint.”

Reporter. “Wait the palm print... sir the palm print was on the gun?” (the reporter exhibits a completely surprised tone)

Henry Wade. “Yes”

Reporter. “Where on the gun? Where on the gun?”

Henry Wade. “Under the uh... on part of the metal... under the gun.” (Henry Wade, 11/24/63 Press Conference) Follow this link.

This ‘evidence’ was only disclosed after the Carcano had been returned to Dallas and after Oswald's death. Considering the gravity of this information, which implicated the main suspect in the assassination, it is perplexing that Fritz, Curry, nor Wade failed to disclose the presence of Oswald's palm print to the gathered media and television reporters whilst Oswald was alive.

The State Of The Evidence.

The palm print evidence cited against Lee Oswald is fraught with significant discrepancies, which seriously undermine its credibility and calls into question the legitimacy of the case against him. Crucially, there are major concerns surrounding the lack of proper chain of custody for this key piece of evidence, thereby casting a shadow over its admissibility and validity in the proceedings.

A litany of issues plagues this particular evidence. These include the conspicuous absence of crucial photographs, contradictory testimonies that present more questions than answers, and a disturbing lack of corroborative details. Further compounding these problems is the issue of delayed disclosure, which only fuels suspicions and raises more doubts about the way this evidence was handled. In my opinion this evidence reeks of a frame up.

55. Day’s Admission Of Perjury?

When requested by the FBI, LT Day specifically declined to sign a sworn affidavit that he had in fact lifted Oswald’s palm print from the barrel of the rifle on the day of the assassination. On that basis alone the print would be inadmissible as evidence in a court of law. (Hear No Evil ; p. 77-78.)

56. Lt Day Vs FBI Agent Drain.

Vincent Drain. “I just don’t believe there was ever a print.” Drain noted that there was increasing pressure on the Dallas police to build evidence in the case. Asked to explain what might have happened, Agent Drain said, “All I can figure is that it (Oswald’s print) was some sort of cushion because they were getting a lot of heat by Sunday night. You could take the print off Oswald’s card and put it on the rifle. Something like this happened.” (Reasonable Doubt; p. 109)

57. Agents Descend On Millers Funeral Home.

Mortician Paul Groody, who was in charge at Millers Funeral Home, was busy preparing Oswald’s remains for burial when agents arrived in the early hours of 11/25/63 to fingerprint the deceased Oswald.

Groody stated:” I had gotten to the funeral home with his body something in the neighbourhood of 11 o’clock at night and it is a several hour procedure to prepare the remains and after this time some-place in the early early morning agents came. Now I say agents because I am not familiar at this moment with whether they were Secret Service or FBI or what they were, but agents did come and when they did come, they fingerprinted and the only reason we knew that they did, they were carrying a satchel and the equipment and ask us if they might have the preparation room to themselves. And after it was all over, we found ink on Lee Harvey's hands showing that they had fingerprinted him, and palm printed him. We had to take that ink back off in order to prepare him for burial and to eliminate that ink” Skip to 3:00:40 Follow this link.

58. Commission Exhibit 399.

“The truth has no defense against a fool determined to believe a lie.” Mark Twain.

Commission Conclusion. “A nearly whole bullet was found on Governor Connolly’s stretcher” (WCR; p. 557.)

What Is Chain Of Custody? Chain of custody is a crucial concept in legal proceedings that refers to the process of maintaining and documenting the handling of evidence. This starts at the moment the evidence is collected at the crime scene and continues through to its presentation in court. The purpose of this process is to protect the evidence from tampering, contamination, or mishandling, and to provide a documented history of its management and control.

With this in mind, how would Henry Wade have legitimised CE399 in a court of law? It would have been imperative for Wade to establish a robust chain of custody for CE 399 proving its legitimacy. This would involve providing documented evidence of every individual who handled the bullet, from its alleged discovery at Parkland Hospital to its transportation and subsequent analysis at the FBI crime lab in Washington, and ultimately to its presentation in court.

In essence, Wade would need to convincingly demonstrate to a jury that CE 399 was the same bullet discovered at Parkland, that it was handled and stored properly at all times, and that it is indeed the bullet that caused the non-fatal wounds to President Kennedy and Governor Connally, as per the single-bullet theory. Establishing a solid chain of custody would be paramount to achieving this. Follow this link.

Darrell C. Tomlinson. First Link In The Custody Chain.

Darrell C. Tomlinson, senior engineer, Parkland Hospital: Discovered bullet on a stretcher in a corridor of the hospital emergency area between 1:00 and 1:50 p.m, November 22, 1963. Called O. P. Wright and pointed out bullet. Tomlinson testifies but is asked very little about his finding of the bullet; and nothing about its appearance or his handling and disposition of it. Unlike most other hospital personnel, no written report covering his activities appears in evidence.

According to CE2011, a document from the FBI located within the Warren Commission Volumes, “Darrell C. Tomlinson was shown Exhibit C1 (CE 399), a rifle slug, by Special Agent Bardwell D. Odum, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Tomlinson stated it appears to be the same one he found on a hospital carriage at Parkland Hospital on November 22, 1963, but he cannot positively identify the bullet as the one he found and showed to O.P. Wright.” (Volume XXIV; p. 412)

During his Commission testimony Tomlinson is not presented with CE399 and asked to identify it as the bullet he discovered on 11/22/63.

O.P. Wright. Second Link In The Custody Chain.

O.P. Wright, Personnel Officer, Parkland Hospital: Received bullet from Tomlinson; or removed it from stretcher after it was pointed out by Tomlinson 1:00-1:50p.m., November 22. Gave it to Richard E. Johnsen shortly thereafter. (Wright not called to testify. No direct statement from him in evidence referring to bullet. He failed to mention it in lengthy report, to hospital administrator, concerning his activities November 22- November 25 (1963), although detailing his handling of President Kennedy’s wristwatch.

According to CE2011, “O.P. Wright, advised Special Agent Bardwell D. Odum that Exhibit C1 (CE 399), a rifle slug, shown to him at the time of the interview, looks like the slug found at Parkland Hospital on November 22, 1963. He advised he could not positively identify (CE 399) as being the same bullet which was found on November 22, 1963.”

However, in November of 1966, Josiah Thompson, author of "Six Seconds in Dallas", undertook a pivotal investigation at Parkland, where he met with Darrell C. Tomlinson and O.P. Wright. These two figures were integral to his objective: to meticulously reconstruct the circumstances surrounding Tomlinson's discovery of the so-called "stretcher bullet".

Guided by Tomlinson and Wright, Thompson endeavoured to re-enact the precise sequence of events that led to the discovery of ‘CE399 at Parkland’. To facilitate this re-enactment, Wright provided Thompson with a prop .30 calibre projectile as a stand-in for ‘399’. During their interaction, Thompson asked Wright to describe the bullet he had obtained from Tomlinson on November 22, 1963. Wright described the projectile as having a "pointed tip" and suggested that it looked similar to "the one you got there in your hand”.

This characterisation from Wright starkly contrasts the appearance of CE 399. When presented with a photograph of CE 399, along with CE 572 (bullets similar to those from Oswald's alleged rifle) and CE 606 (bullets similar to those from Oswald's alleged revolver), Wright rejected them all. None of them resembled the bullet Tomlinson had discovered on a stretcher that day.

Upon conclusion of their meeting, Thompson recounted a moment that further cast doubt on 399. As he prepared to leave Parkland, Wright approached him with the statement "Say, that single bullet photo you kept showing me… was that the one that was supposed to have been found here?" To which Thompson affirmed, "Yes." Wright's response, a simple "Uh...huh," was delivered with an expressionless face before he turned and returned to his office.

Thompson interpreted this interaction as a tacit rejection of CE 399 as the bullet Tomlinson handed over to Wright that day.

Adding to this ambiguity, a declassified document “dated June 20, 1964, from Gordon Shankland, SAC Dallas, to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, confirms: “Neither Parkland’s DARRELL C. TOMLINSON nor O. P. WRIGHT can identify this bullet.” which of course contradicts the information in CE2011. (The Bastard Bullet; p.38. Volume XXIV; p 412.Last Seconds In Dallas, Page 24/26). Follow this link.

The inability of both Wright and Tomlinson to definitively identify CE 399 as the bullet they handled that day casts serious doubt over its credibility as evidence.

Richard E Johnsen. Special Agent, U.S Secret Service. Third Link In The Custody Chain.

The ambiguity surrounding CE 399 continued within the Secret Service's custody chain. Agent Johnsen received bullet from O.P. Wright at Parkland shortly before 2:00p.m., November 22,1963. Transmitted to James Rowley same day. “On June 24, 1964, Special Agent Richard E. Johnsen, United States Secret Service, Washington, D.C., was shown Exhibit C1 (CE 399), a rifle bullet, by Special Agent Elmer Lee Todd, Federal Bureau of Investigation. Johnson advised he could not identify this bullet as the one he obtained from O. P. Wright, Parkland Hospital, Dallas Texas, and gave to James Rowley, Chief, United States Secret Service, Washington D.C., on November 22, 1963.” Agent Johnsen was not called to testify. (Commission Exhibit 2011, Volume XXIV, p. 412, The Bastard Bullet; p.38)

James. J. Rowley. Chief, U.S. Secret Service. Fourth Link In The Custody Chain.

“Received bullet from Johnsen on November 22, 1963. Gave it to FBI Special Agent Todd same day. Rowley testifies July 7th,1964, but is not asked anything about the bullet. No written statement from him concerning his possession of it. On June 24, 1964, James Rowley, Chief, United States Secret Service, Washington, D.C., was shown exhibit C1(CE 399), a rifle bullet, by Special Agent Elmer Lee Todd. Rowley advised he could not identify this bullet as the one he had received from Special Agent Richard E. Johnson and gave to Special Agent Todd on November 22, 1963”. (The Bastard Bullet; p 38. Commission Exhibit 2011, Volume XXIV, p. 412)

Elmer Lee Todd. Special Agent. FBI. Fifth Link In The Custody Chain.

Received bullet from Rowley in Washington, D.C., November 221963. Upon receipt, Todd marked bullet with initials at FBI Investigation Laboratory. Gave it to Robert A. Frazier same day. In 1964, Special Agent Elmer Lee Todd, identified C1 (CE 399), a rifle bullet, as the same one he had received from James Rowley, Chief of the United States Secret Service, on November 22, 1963. This identification was based on his own marked initials on the bullet upon its receipt at the FBI Laboratory.”

Robert Frazier. Firearms Identification Expert, FBI. Sixth Link In Custody Chain.

“Received bullet from Todd in FBI laboratory, Washington, D.C., November 22, 1963. Frazier put his initials on it.” However according to Robert Frazier's detailed notes, 399 was transferred into his custody by Special Agent Elmer Lee Todd at 7:30 p.m. on November 22, 1963. However, an examination of the envelope filled out by Agent Todd, documenting the transfer from Rowley, reveals that he did not receive the bullet from Rowley until 8:50 p.m. on 11/22/63. This clear discrepancy of 1:20:00 calls into question the authenticity and validity of the bullet's chain of custody. The chronology here is of paramount importance.

John F. Gallagher, spectrographer, Special Agent, FBI.

“Made spectrographic examination of bullet, (date not given, but apparently prior to March 31, 1966) No written statement from Gallagher appears in evidence. He was not called to testify until September 15, 1964, less than two weeks prior to publication of the Warren Commission Report. His entire seven-page testimony is taken up with a discussion of neutron activation analysis, as it pertains to determination of whether or not an individual has fired a weapon. (Practice has been exposed as junk science) Counsel Norman Redlich failed to ask Gallagher a single question regarding his spectrographic examination of bullet 399.” (The Bastard Bullet;p. 39/39) Follow this linkand and this link.

Melvin A. Eisenberg, assistant counsel, Warren Commission: “Received bullet from FBI in Washington, D.C., March 24, 1964. Transmitted to Joseph D. Nichol same day”. (The Bastard Bullet; p. 39)

Joseph D. Nichol, Superintendent, Bureau Of Criminal Identification, State Of Illinois. Received bullet 399 from Eisenberg in latter’s office, together with other bullets and fragments, Washington, D.C., March 24th, 1964. Made ballistics comparisons with other bullets and fragments. Date not given for return of 399 to FBI custody. Nicol testifies April 1, 1964. Counsel Eisenberg failed to ask his opinion as to whether or not 399 could have caused Governor Connally’s wounds. (The Bastard Bullet; p. 40)

Bardwell D. Odum, Special Agent, FBI. On June 24, 1964, he is alleged to have shown bullet 399 to Tomlinson and Wright. Odum not called to testify. No direct written statement from him appears in evidence covering his June 12 interviews with Tomlinson and Wright. His written report on unrelated matter, date July 10, 1964, is presented in evidence.

In 2002 Gary Aguilar and Josiah Thompson approached retired FBI Special Agent Bardwell Odum to review some crucial documents, including CE 2011. Odum expressed surprise and denial over his involvement with CE 399. “I didn’t show it to anybody at Parkland. I didn’t even have any bullet. I don’t know where you got that from, but it is wrong. Mr. Odum remarked that he doubted he would have ever forgotten investigating so important a piece of evidence. But even if he had done the work, and later forgotten about it, he said he would certainly have turned in a “302” report covering something that important. There is no 302 report from Odum in the record. (The Bastard Bullet; p. 40) Follow this link.

Elmer Lee Todd. Special Agent, FBI. On June 24, 1964, he showed bullet 399 to Johnsen and Rowley. Todd not called to testify. No direct written statement from him appears in evidence concerning his June 24 interviews with Johnsen and Rowley. (The Bastard Bullet; p. 41)

Which Stretcher? Connelly or Fuller.

Commission Conclusion. “Although Tomlinson was not certain whether the bullet came from Connally’s stretcher or the adjacent one, the Commission has concluded that the bullet came from the Governor’s stretcher.” (WCR; p. 81)

Evidence In The Record Which Refutes Commission Conclusion.

During his testimony to the Warren Commission, Tomlinson gave a description of the stretcher that he took off the elevator at Parkland.

Arlen Specter. “Was there anything on the elevator at that time?”

Darrell Tomlinson. “There was one stretcher.” Arlen Specter. “And describe the appearance of that stretcher, if you will, please.” Darrell Tomlinson. “I believe that stretcher had sheets on it and had a white covering on the pad.” (Volume VI; p. 129)

Tomlinson’s description of the stretcher is collaborated by R. J. Jimison, an orderly at Parkland. Who testified to the Warren Commission that:

R. J. Jimison. “I came along and pushed it [ Connally’s stretcher] onto the elevator myself and loaded it on and pushed the door closed.

Arlen Specter. “What was on the stretcher at that time?”

R. J. Jimison. “I noticed nothing more than a little flat mattress and two sheets as usual.” (Volume VI; p. 126)

Tomlinson then testifies to his initial discovery of the bullet and which stretcher he believed the bullet was found on.

Darrell Tomlinson. I pushed it back up against the wall.

Arlen Specter. What, if anything, happened then?

Darrell Tomlinson. I bumped the wall and a spent cartridge or bullet rolled out that apparently had been lodged under the edge of the mat.

Arlen Specter. And that was from which stretcher?

Darrell Tomlinson. I believe that it was “B”.

Arlen Specter. And what was on “B”, if you recall; if anything?

Darrell Tomlinson. Well, at one end they had one or two sheets rolled up; I didn’t examine them. They were bloody. They were rolled up on the east end of it and there were a few surgical instruments on the opposite end and a sterile pack or so. (Volume VI; p. 130/131)

In the following testimony, Specter appears to engage in a strategy aimed at creating confusion or obfuscating the clarity around which stretcher the bullet was found on. He seemingly contradicts Tomlinson's assertion that the bullet was discovered on stretcher B, attempting to steer the testimony towards an affirmation that the bullet was instead found on stretcher A.

This attempt could be interpreted as a deliberate strategy to realign Tomlinson's account with a predetermined narrative that supports the Commission's conclusion. Essentially, Specter might be trying to manipulate Tomlinson's testimony to fit a particular storyline rather than objectively following the evidence presented.

Arlen Specter. “And at that time, we started our discussion, it was your recollection at that point that the bullet came off of stretcher A, was it not?”

Darrell Tomlinson. “B.”

Arlen Specter. “Pardon me, stretcher B, but it was stretcher A that you took off of the elevator.” (Volume VI; p.131)

Experiencing clear frustration with Specter's line of questioning, Tomlinson reiterated the sequence of events leading to his discovery of the bullet. What is noteworthy about this portion of his testimony is Tomlinson's confirmation that both stretchers A and B were left unattended and unprotected at the elevator at the Emergency Department. This lack of security presented a substantial window of opportunity for anyone with access to manipulate the evidence on the stretchers, either by removing or adding items. Consequently, this throws into sharp relief the credibility and integrity of any evidence collected from the stretchers at Parkland Hospital on November 22, 1963.

Darrell Tomlinson. Here’s the deal-- I rolled that thing off, we got a call, and went to second floor, picked the man up and brought him down. He went on over across, to clear out of the emergency area, but across from it, and picked up two pints of, I believe it was, blood. He told me to hold for him, he had to get right back to the operating room, so I held, and the minute he hit there, we took off for the second floor and I came, back to the ground. Now, I don’t know how many people went through that-I don’t know how many people hit them- I don’t know anything about what could have happened to them in between the time I was gone, and I made several trips before I discovered the bullet on the end of it there. (Volume VI; p.132/133)

Secret Service Agent Johnsen communicates Wright's account of the characteristics of the stretcher where the bullet was found:

Richard E. Johnsen, Commission Exhibit 1024. November 22, 1963, 7:30 pm.

“The attached expended bullet was received by me about 5 min., prior to Mrs. Kennedy’s departure from the hospital. It was found on one of the stretchers located in the emergency ward of the hospital. Also on this stretcher was rubber gloves, a stethoscope and other doctors’ paraphernalia. It could not be determined who used this stretcher or if President Kennedy had occupied it. No further information obtained. Name of person from who I received this bullet: Mr O.P. Wright. Personnel Director of Security. Dallas County Hospital District. By Richard E Johnsen. Special Agent. 7:30pm. Nov 22, 1963.”

Richard E. Johnsen to Chief James Rowley. “The only information I was able to get from Wright prior to departure of Mrs. Kennedy and the casket was that the bullet had been found on a stretcher which President Kennedy may have been placed on. He also stated that he found rubber gloves, a stethoscope, and other doctors’ paraphernalia on this same stretcher. CE1024. (Volume XVIII; p. 798-800)

In November 1966, Wright reaffirmed this description of stretcher B to Tink Thompson. Wright also verified “that the stretcher on which the bullet rested was the one in the corner—the one blocking the men’s room door.” (Six Seconds In Dallas; p. 156)

Ronald Fuller. Ronnie Fuller was received at Parkland Hospital’s Emergency Department around 12:54pm on November 22, 1963. The toddler, aged two and a half years, had sustained an injury to his chin, “which was bleeding profusely. Fuller was placed on a stretcher in the hallway near the nurse’s station before being carried to Major Medicine. Fullers’ stretcher was described as having sheets which were soiled in blood. Rosa Majors told Tink Thompson that she and Era Lumpkin had used gauze pads to clean the child, that either she or Era had been wearing rubber gloves, and that Era had a stethoscope. She cannot remember what happened to this equipment... but it was possible that it was left behind on the stretcher when the two aides carried Ronald Fuller into Major Medicine.” (Six Seconds In Dallas; p. 161/164.)

Rosa Majors, Nurse Aid Parkland Hospital. Told Tink Thompson that while in trauma room 2 “she removed the Governor’s trousers, shoes, and socks. After removing his trousers, she held them up and went through the pockets for valuables. Had a bullet fallen out of the Governor’s thigh, it would have been trapped in his trousers. When Rosa held them up, any such bullet should have fallen out and been discovered at that time. Rosa told Thompson she never saw any bullet while she was caring for Governor Connally. Much later she heard that a bullet was supposed to have been found on his stretcher. Rosa can’t conceive where such a bullet could have come from.” (Six Seconds In Dallas; p.159)

The Condition Of CE399.

Commission Conclusion: “The stretcher bullet weighed 158.6 grains, or several grains less than the average Western Cartridge Co. 6.5mm Mannlicher Carcano bullet. It was slightly flattened, but otherwise unmutilated.” (WCR; p. 557)

399 is purported to be responsible for inflicting seven non-fatal wounds on both President Kennedy and Governor Connally. According to the Commission

1. The bullet penetrated President Kennedy's upper back, traversing through his body. 2. It then emerged from President Kennedy's throat, just below the Adam's apple, creating an exit wound. 3. Continuing its trajectory, the bullet entered Governor Connally's back, near his right armpit, passing through his body. 4. In the process, it shattered several inches of his fifth rib on the right side before exiting his chest. 5. The same bullet is then believed to have passed through Connally's right wrist, fracturing the distal radius bone. 6. Finally, it lodged itself into Connally's left thigh, ending its alleged trajectory.

The following witness testimony is a direct challenge to CE399.

Dr Robert Shaw. Parkland Hospital. Operated on Gov Connally. “The bullet struck lateral to the shoulder blade. Stripped out approximately 10 cm of the fifth rib, driving fragments of the rib into his chest. Went on and struck his radius bone of his lower arm at this point [pointing to wrist] and a small fragment of bullet, entered the inner aspect of the lower left thigh. I have never seen a bullet that caused as much boney damage as you found in the case of Governor Connally remain as a pristine bullet. Follow this link.

<strong" target="_blank">Dr Robert Shaw.

Arlen Specter. What is your opinion as to whether bullet 399 could have inflicted all of the wounds on the Governor, then, without respect at this point to the wound of the President’s neck?

Dr Robert Shaw. I feel that there would be some difficulty in explaining all of the wounds as being inflicted by bullet Exhibit 399 without causing more in the way of loss of substance to the bullet or deformation of the bullet. (Discussion off the record.)

Dr Charles Gregory. Parkland Hospital. Operated on Gov Connally.

Arlen Specter. “I call your attention to Commission Exhibit No. 399, which is a bullet and ask you first if you have had an opportunity to examine that earlier today?”

Dr Charles Gregory. “I have.”

Arlen Specter. “What opinion, if any, do you have as to whether that bullet could have produced the wound on the Governor's right wrist and remained as intact as it is at the present time?”

Dr Charles Gregory. “In examining this bullet, I find a small flake has been either knocked off or removed from the rounded end of the missile. I was told that this was removed for the purpose of analysis. The only other deformity which I find is at the base of the missile at the point where it Joined the cartridge carrying the powder, I presume, and this is somewhat flattened and deflected, distorted. There is some irregularity of the darker metal within which I presume to represent lead. The only way that this missile could have produced this wound in my view, was to have entered the wrist backward.” (Volume IV; P. 121)

Commander James Humes, Autopsy Pathologist.

Arlen Specter. “Now looking at that bullet, Exhibit 399, Doctor Humes…could that missile have made the wound on Governor Connally's right wrist?”

Commander James Humes. “I think that that is most unlikely…Also going to Exhibit 392, the report from Parkland Hospital, the following sentence referring to the examination of the wound of the wrist is found: Small bits of metal were encountered at various levels throughout the wound, and these were, wherever they were identified and could be picked up, picked up and submitted to the pathology department for identification and examination. The reason I believe it most unlikely that this missile could have inflicted either of these wounds is that this missile is basically intact; its jacket appears to me to be intact, and I do not understand how it could possibly have left fragments in either of these locations.”

Arlen Specter. “Dr. Humes, under your opinion which you have just given us, what effect, if any, would that have on whether this bullet, 399, could have been the one to lodge in Governor Connally's thigh?”

Commander James Humes. “I think that extremely unlikely. The reports, again Exhibit 392 from Parkland, tell of an entrance wound on the lower midthigh of the Governor, and X-rays taken there are described as showing metallic fragments in the bone, which apparently by this report were not removed and are still present in Governor Connally's thigh. I can't conceive of where they came from this missile.” (Volume II; p 375-376)

Pierre Finck, Autopsy Patholigist.

Arlen Specter “And could it [CE399] have been the bullet which inflicted the wound on Governor Connally's right wrist?”

Pierre Finck. “No; for the reason that there are too many fragments described in that wrist.” (Volume II; p. 382)

Despite the extensive damage described in the above testimonies, the bullet itself remained remarkably clean, as confirmed by Special Agent Robert Frazier:

Melvin Eisenberg. “Did you prepare the bullet in any way for examination? that is, did you clean it or in any way alter it?”

Robert Frazier. “No, sir; it was not necessary. The bullet was clean and it was not necessary to change it in any way.”

Melvin Eisenberg. “There was no blood or similar material on the bullet when you received it?”

Robert Frazier. “Not any which would interfere with the examination, no, sir. Now there may have been slight traces which could have been removed just in ordinary handling, but it wasn’t necessary to actually clean blood or tissue off the bullet.” (Volume III; p. 128-129)

However, blood was retained on two fragments alleged to have been found within the Presidential limousine, CE 567&569.

Melvin Eisenberg. “Getting back to the two bullet fragments mentioned, Mr. Frazier, did you alter them in any way after they had been received in the laboratory, by way of cleaning or otherwise?”

Robert Frazier. “No, sir; there was a very slight residue of blood or some other material adhering, but it did not interfere with the examination. It was wiped off to clean up the bullet for examination, but it actually would not have been necessary.” (Volume III; p.437)

How would Henry Wade have gotten CE399 into evidence? Taking into account all the evidence presented, let's examine the potential issues Henry Wade might have encountered in attempting to admit CE399 into evidence. Each point will highlight significant inconsistencies and flaws that would seriously challenge the prosecution's narrative.

1. Which Stretcher? There is considerable ambiguity regarding which stretcher the bullet was found on. Tomlinson, the person who discovered the bullet, stated that he thought he had found it on stretcher B, whereas the Warren Commission concluded it came from Governor Connally’s stretcher (stretcher A). Wade would need to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the bullet was indeed discovered on Connally’s stretcher, despite the contradictory testimony.

2. Unsecured and Unattended Stretcher. Tomlinson’s testimony highlights that both stretchers A and B were left unattended and unsecured at the hospital elevator. This creates an opportunity for tampering, casting serious doubt on the integrity and reliability of any evidence found on these stretchers.

3. Bullet Identification. Wade would face significant difficulties in establishing a clear chain of custody for the bullet (CE399). Key figures including Tomlinson, Wright, Agent Johnsen, and Chief Rowley, could not definitively identify CE399 as the bullet they handled. In fact, Wright, retired Dallas Police Officer, flat out rejected it as the bullet he had obtained from Tomlinson. The only person who could identify it, prior to its arrival at the FBI Lab was Special Agent Todd, who had conflicting documentation about the timing of the bullet’s retrieval.

4. Timing Discrepancy. This inconsistency between the times documented by Todd and Frazier further undermines the credibility of CE399 as a key piece of evidence. Todd noted the retrieval time as 8:50pm on 11/22/63, whereas Frazier claimed he received the bullet at 7:30pm the same day.

5. Lack of Physical Evidence. There's a lack of physical evidence linking the bullet to Governor Connally. Nurse Aid Rosa Majors, who removed the Governor's clothing, did not find any bullet when she went through the Governor's pockets. Had a bullet fallen out of the Governor’s thigh, it would have been trapped in his trousers This brings into question the very presence of the bullet on Connally's stretcher.

6. Unnoticed Bullet. It seems implausible that the bullet, if indeed it was on the stretcher from the start, would have gone unnoticed throughout Connally's medical treatment. Governor Connally was moved from the limousine to the stretcher, brought to Trauma Room 2, had his clothing removed, was transported to the second-floor operating theatre, and then transferred to an operating table. It's highly unlikely that through all these movements and transitions, a bullet would not only remain undetected but also not fall off the stretcher. Additionally, the noise of a bullet rattling on a metal stretcher as it was moved across different floors of the hospital is something that should have drawn attention.

7. No Witnesses to Falling Bullet. It's also worth questioning why there were no eyewitness accounts of the bullet falling from Connally during his movement and treatment. If the bullet had been lodged in his body, the multiple movements and handling would have provided ample opportunity for it to dislodge and fall out in clear view of the medical personnel present. The absence of any such observations raises further doubts about the presence of the bullet on Connally's stretcher.

8. The Condition of CE399. Despite causing seven non-fatal wounds on both President Kennedy and Governor Connally, including significant bone damage, 399 was found in relatively pristine condition. As noted in the Commission Conclusion, the "stretcher bullet" weighed only several grains less than a standard 6.5mm Mannlicher Carcano bullet and was slightly flattened, but otherwise unmutilated. This discrepancy was noted by several expert witnesses, including Dr. Robert Shaw, Dr. Charles Gregory, Commander James Humes, and Pierre Finck. Each cast doubt on the ability of CE399 to cause the observed injuries without suffering more substantial deformation or loss of mass. For Henry Wade, the pristine condition of CE399 relative to the extensive physical trauma it allegedly caused would be a significant hurdle in convincing a jury of its role in the sequence of wounds.

9. Cleanliness of CE399. Another point of contention would be the cleanliness of CE399. Special Agent Robert Frazier confirmed that CE399 was clean upon examination, with no need for removal of blood or tissue. This would be extremely unusual for a bullet that had supposedly passed through two bodies, breaking bone and embedding fragments along its path. This lack of expected biological contamination casts further doubt on the bullet's history and raises questions about the official narrative.

Additionally, Commission Exhibits (CE) 567 and 569, which are bullet fragments alleged to have been found within the Presidential limousine, were reported to have a residue of blood or some other material adhering to them. This was confirmed by Robert Frazier's testimony, stating that there was a slight residue of blood or some other material on 567 and 569. Despite this residue not interfering with the examination, it was wiped off to clean the bullet for examination. The presence of blood on these fragments, yet its notable absence on CE399, which supposedly passed through two bodies, is an additional challenge to the case's narrative. If the bullet that caused the wounds to President Kennedy and Governor Connally had been as clean as reported, why would fragments found within the limousine retain blood residues? This discrepancy significantly undermines the credibility of CE399 as the bullet that inflicted the seven wounds. For the prosecution, these questions would significantly complicate efforts to validate the evidentiary value of CE399. The bullet's unexplained cleanliness would stand as a glaring inconsistency in the narrative of its path through two bodies, thereby undermining the case against Oswald.

59. CE399, A Hard Act To Fellow.

Dr Joseph Dolce, Chief Consultant of Wound Ballistics for the US Army, supervised the ballistic test conducted by the Warren Commission. Even though he oversaw the Commission’s own ballistics tests, he was not called to give testimony before the Warren Commission. This is what Dr Dolce had to say regarding Commission Exhibit 399: “No it could not have caused all the wounds, because our experiments have showed beyond any doubt that merely shooting the wrist deformed the bullet drastically and yet this bullet [399] came out as almost a perfectly normal pristine bullet… And so, they gave us the original rifle, the Mannlicher Carcano plus 100 bullets, 6.5mm, and we went, and we shot the cadaver wrist as I have just mentioned and in every instance the front or the tip of the bullet was smashed. It’s impossible for bullet to strike a bone, even at low velocity and still come with the perfectly normal tip. The tip of this bullet was absolutely not deformed in no instance whatsoever, in no amount. Under no circumstances do I feel that this bullet [399] could hit the wrist and still not be deformed. We proved that by experiments.” Skip to 42:17 Skipto 42:17 in video.

CE399=Magic Bullet. CE572=Cotton Wadding CE853=Goat CE856=Cadaver Wrist.

60. CE543, The Dented Lip.

“There were no shells dented in that manner by the HSCA…I have never seen a case dented like this.” Howard Donahue. Follow this link.

The discovery of three spent shells on the sixth-floor post-assassination raised significant questions, and notably, CE 543 stands out as a considerable anomaly in the Commission's claim that a lone gunman fired three shots at President Kennedy.

In his compelling and meticulously researched article, "The Dented Bullet Shell: Hard Evidence Of Conspiracy In The JFK Assassination," Michael T. Griffith sheds light on the dubious authenticity of CE 543 as a piece of evidence from the day of the assassination.

He cites the insights of fellow researcher Dr. Michael Kurtz, who asserts unequivocally, "CE 543 could not have fired a bullet on the day of the assassination. Moreover, it could not have been discharged from the rifle that Oswald allegedly utilized."

In the book I coauthored, ”Case Not Closed”, I sought comment upon CE543 from fellow DPUK member Peter Antill. Peter is a weapons enthusiast who shared with me, his opinion regarding the complexities and irregularities presented by CE543. Antill's analysis revealed that “One of the more striking characteristics of CE 543 is a significant inward-facing dent in the case lip. This raises the question of how and when this damage could have occurred.

“Researchers have experimented in throwing an empty Carcano case against a wall or standing on it but failed to do any damage. However, one researcher inflicted exactly the same damage seen on CE 543 on an empty cartridge case while he was loading it into his own rifle.

“Firing a round results in both the case and its lip expanding slightly and hence there is an increased chance of the case catching on a lip below where the barrel meets the breach if someone tries to subsequently chamber it.

“If CE 543 had been a live round, such damage would not have been possible as the bullet would have helped to guide the round smoothly into the chamber. This means that either the damage was done before the assassination (and therefore the case could not have been used that day) or if it occurred during it, it raises the question as to why the shooter would waste time trying to manually chamber an empty case.

Signs of Being Dry Fired

“According to CE 2968 (a letter from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to Commission Counsel J. Lee Rankin, dated 2 June 1964) CE 543 was found with three sets of marks on the base which were not found on the other cases fired through the Carcano, as well as other marks which indicated it had been loaded into, and extracted from a weapon, at least three times. In addition, CE 543 had a deeper, more concave dent in its primer (where it had been struck by the firing pin), a characteristic found with dry fired cartridge cases. The FBI actually reproduced this effect on CE 557, an empty case dry fired in the Carcano for comparison purposes.

Marks from the Magazine Follower

“The only marks that link CE 543 to the Carcano were produced by the magazine follower. These marks are caused by the pressure of the magazine follower on the last round in the clip, which pushes the remaining rounds in the clip upwards as their predecessors are chambered and then ejected from the rifle.

“When the final round is chambered, the clip falls past the magazine follower and drops out of the bottom of the magazine well. While other cases had similar marks, the point is that these marks could not have been caused by the Carcano's magazine follower on the day of the assassination as the last round in the clip (CE 141) was unfired and still chambered in the rifle when it was found.

The Chamber Impression

“CE 543 lacks a characteristic displayed by all the other cartridge cases (CE 544, CE 545 and CE 577) that have been chambered in the Carcano - a distinct impression along one side. Even CE 141 (the live round), showed a similar, if less pronounced, impression.

“This was probably because it wasn't fired - firing (where the case expands slightly) would accentuate any marks or impressions caused by the chamber. If CE 543 is supposed to have been fired in the Carcano, how could it be missing this distinct impression?” (Case Not Closed; p. 141-145)

Final Summation.

I wish to conclude my article with a poignant reflection on the hope and loss that defined 1960s America. A profound representation of these conflicting emotions can be found in Robert Kennedy's speech, 'The Mindless Menace of Violence.' This speech not only encapsulates the tragic dichotomy of the era but also continues to resonate today, as it stands as a timeless admonition against violence and a plea for compassion and understanding. It inculpates the fear and brutality that marred that period and yet carries a message of hope, encapsulating the complex spirit of a time that will forever leave its mark on the nation's history.

The Mindless Menace of Violence

“Mr. Chairman, ladies and gentlemen, I speak to you under different circumstances than I had intended to just twenty-four hours ago. For this is a time of shame and a time of sorrow. It is not a day for politics.

I have saved this one opportunity–my only event of today–to speak briefly to you about the mindless menace of violence in America which again stains our land and every one of our lives. It’s not the concern of any one race. The victims of the violence are black and white, rich and poor, young and old, famous and unknown. They are, most important of all, human beings whom other human beings loved and needed. No one–no matter where he lives or what he does–can be certain whom next will suffer from some senseless act of bloodshed.

And yet it goes on and on and on in this country of ours. Why? What has violence ever accomplished? What has it ever created? No martyr’s cause has ever been stilled by an assassin’s bullet. No wrongs have ever been righted by riots and civil disorders. A sniper is only a coward, not a hero; and an uncontrolled or uncontrollable mob is only the voice of madness, not the voice of the people. Whenever any American’s life is taken by another American unnecessarily–whether it is done in the name of the law or in defiance of the law, by one man or by a gang, in cold blood or in passion, in an attack of violence or in response to violence–whenever we tear at the fabric of our lives which another man has painfully and clumsily woven for himself and his children–whenever we do this, then the whole nation is degraded.

“Among free men,” said Abraham Lincoln, “there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and those who take such appeal are sure to lose their case and pay the cost.” Yet we seemingly tolerate a rising level of violence that ignores our common humanity and our claims to civilization alike. We calmly accept newspaper reports of civilian slaughter in far off lands. We glorify killing on movie and television screens and we call it entertainment. We make it easier for men of all shades of sanity to acquire weapons and ammunition that they desire. Too often we honor swagger and bluster and the wielders of force. Too often we excuse those who are willing to build their own lives on the shattered dreams of other human beings. Some Americans who preach nonviolence abroad fail to practice it here at home.

Some who accuse others of rioting, and inciting riots, have by their own conduct invited them. Some look for scapegoats; others look for conspiracies. But this much is clear: violence breeds violence; repression breeds retaliation; and only a cleansing of our whole society can remove this sickness from our souls. For there is another kind of violence, slower but just as deadly, destructive as the shot or the bomb in the night. This is the violence of institutions–indifference, inaction, and decay.

This is the violence that afflicts the poor, that poisons relations between men because their skin has different colors. This is a slow destruction of a child by hunger, and schools without books, and homes without heat in the winter. This is the breaking of a man’s spirit by denying him the chance to stand as a father and as a man amongst other men. And this too afflicts us all. For when you teach a man to hate and to fear his brother, when you teach that he is a lesser man because of his color or his beliefs or the policies that he pursues, when you teach that those who differ from you threaten your freedom or your job or your home or your family, then you also learn to confront others not as fellow citizens but as enemies–to be met not with cooperation but with conquest, to be subjugated and to be mastered.

We learn, at the last, to look at our brothers as alien, alien men with whom we share a city, but not a community, men bound to us in common dwelling, but not in a common effort. We learn to share only a common fear–only a common desire to retreat from each other–only a common impulse to meet disagreement with force. For all this there are no final answers for those of us who are American citizens. Yet we know what we must do, and that is to achieve true justice among all of our fellow citizens.

The question is not what programs we should seek to enact. The question is whether we can find in our own midst and in our own hearts that leadership of humane purpose that will recognize the terrible truths of our existence. We must admit the vanity of our false distinctions, the false distinctions among men, and learn to find our own advancement in search for the advancement of all. We must admit to ourselves that our children’s future cannot be built on the misfortune of another’s. We must recognize that this short life can neither be ennobled or enriched by hatred or by revenge.

Of course we cannot banish it with a program, nor with a resolution. But we can perhaps remember–if only for a time–that those who live with us are our brothers, that they share with us the same short moment of life, that they seek–as do we–nothing but the chance to live out their lives in purpose and in happiness, winning what satisfaction and fulfillment that they can.

Surely this bond of common fate, surely this bond of common goals can begin to teach us something. Surely we can learn, at the least, to look around at those of us, of our fellow man, and surely we can begin to work a little harder to bind up the wounds among us and to become in our hearts brothers and countrymen once again. Tennyson wrote in Ulysses: that which we are, we are; one equal temper of heroic hearts, made weak by time and fate, but strong in will; to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Thank you very much.” - Robert Francis Kennedy. Follow this link.