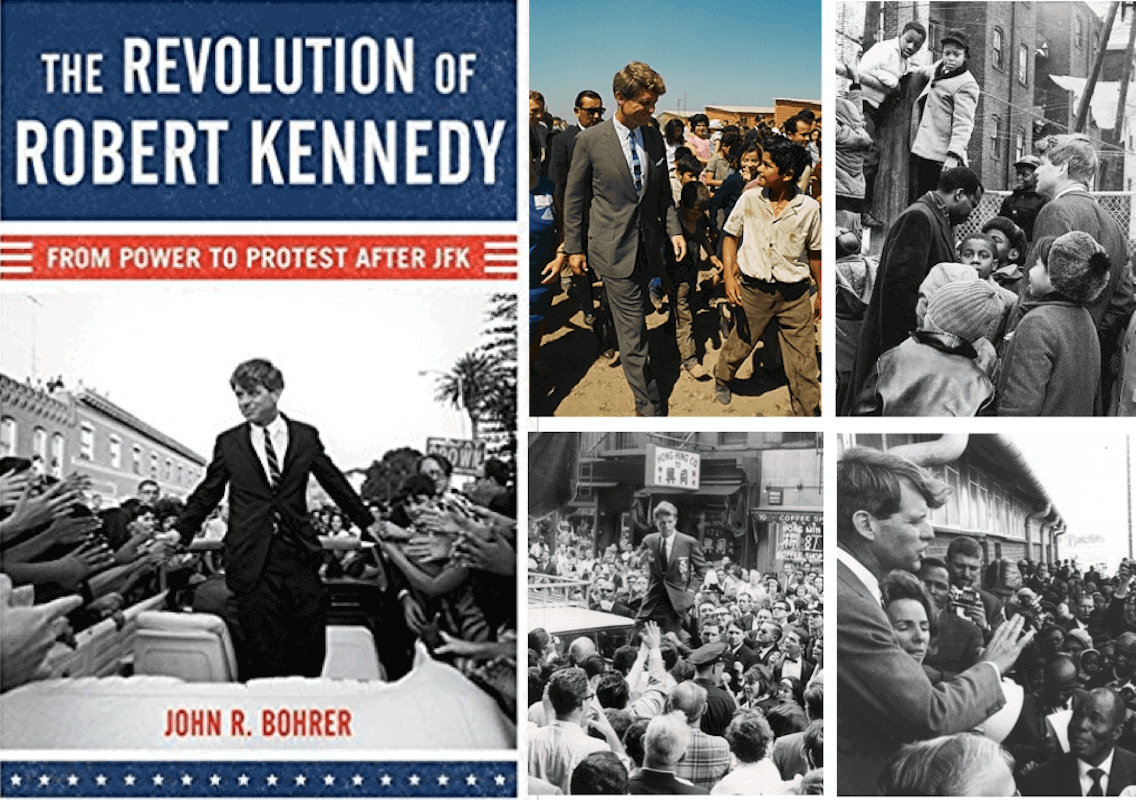

This past June, John R. Bohrer published an unusual book about RFK. Entitled The Revolution of Robert Kennedy, it focuses on the period of time from after President Kennedy’s assassination to the end of 1966. In other words, it covers only three years, but they were crucial years. To anyone really interested in RFK, it seems to me a volume of the greatest interest. Not only is it unique in its focus, but, unlike Tye, Bohrer has done some valuable research on his subject, and unearthed some new and important information about the senator. His book shows that you can reveal a lot about a person if you study your subject from a small window but tell more about that frame than others do.

In his introduction, Bohrer mentions something I was not aware of. Bobby Kennedy had offered to resign his position as Attorney General in advance of his brother’s 1964 reelection campaign. It had become clear to RFK that the opposition to his actions in the civil rights arena had done much to alienate both Democratic voters and politicians in the south. He saw this as being a serous liability to President Kennedy’s 1964 reelection. JFK refused to entertain the offer, but on November 20, 1963 Bobby Kennedy was despondent about the issue and still thought it was the right thing to do. After all, as the author notes, Bobby had run JFK’s 1952 senatorial campaign. In 1956, as a kind of dress rehearsal for 1960, he joined up with Adlai Stevenson’s presidential campaign. So he knew how brutal these things could become, and the impact his name and acts could have on the calculus for 1964.

Bohrer portrays the assassination of President Kennedy as something that seriously affected Robert Kennedy and made him rethink his ideas about politics, in the sense that ideas and ideals mattered. It should not be all about practicality and vote counting. In fact, one of the recurring words in his speeches after his brother’s death was “revolution”. In visiting Peru, he told students who had assembled to meet him that the revolution was their responsibility. They must be wise and humane so that it will be peaceful and successful: “But a revolution will come whether we will it or not. We can affect its character, we cannot alter its inevitability.” (Bohrer, p. 8) That speech was made while RFK was a senator from New York. Ask yourself the last time you heard a US senator encourage revolution anywhere in the world.

II

When Attorney General Robert Kennedy got the word of his brother’s death, he talked with his press secretary Ed Guthman. The latter commented that this might bring people together. RFK replied prophetically that no, this was going to make things worse. (Bohrer, p. 12) He actually pondered whether he should resign. But President Johnson sent Clark Clifford to persuade him to stay in his position. Within days, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had pulled RFK’s private line out of his inner office. And with that, the Attorney General realized that his power in the Justice Department had been severely curtailed. As long as his brother was president, he had some leverage over Hoover. Without the White House behind him, Hoover was free to chart his own course. (p. 15) Again, he thought of resigning. But he decided to stay on until the Civil Rights bill that he and his brother had worked so hard for was passed. A main thesis of Bohrer’s book is that although his brother was gone, and JFK had been the main fulcrum of his life, Bobby now began to search for a new rudder. And that would turn out to be keeping the legacy of President Kennedy alive. Because, as the book outlines, in addition to Hoover, RFK saw certain moves that President Johnson made as being counter to what his brother had been about.

One of these was the ascension of Thomas Mann on the Latin American desk of the State Department. Under President Kennedy, Mann had been Ambassador to Mexico. Within three weeks of his murder, Mann was promoted by Johnson to Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, and also to govern the US Agency for International Development. As Arthur Schlesinger has noted, and as RFK agreed, this double appointment seemed aimed at neutralizing JFK’s rather moderate Alliance for Progress program in Latin America. (Bohrer, p. 19)

In fact, a couple of months later, Mann held a conference for the State Department’s Latin American diplomatic corps. During his address, he did not mention the Alliance for Progress. He said the USA should not intervene against dictators if they were friendly to American business interests. But they should oppose communists whatever their policies would be. The speech was leaked to the press and characterized as advocating American commercial profits over Latin American political reform. The policy became known as the Mann Doctrine. (Walter LaFeber Inevitable Revolutions, p. 157)

Mann’s speech was instrumental in the American backed coup that occurred several weeks later in Brazil. The following year, Mann and Johnson worked together in order to halt the movement to reinstall Juan Bosch in the Dominican Republic. President Kennedy had ordered severe economic sanctions against the military plotters who had ousted the democratically elected President Bosch in September of 1963. In their opposition to Bosch, Mann and LBJ’s actions eventually led to a large military intervention by the Marines to halt his restoration. (See LaFeber, pp. 157-58; Donald Gibson, Battling Wall Street, pp. 78-80)

What RFK and Schlesinger understood was that Johnson’s favoring of Mann’s hardline approach was a direct challenge to what Kennedy wished to achieve with his Alliance for Progress. (For a long, detailed analysis of this program under JFK, see Schlesinger’s Robert Kennedy and His Times, pp. 494-574) One of the aims of the 1961 Alliance program was to stimulate economic growth by making loans to Latin American countries directly from the American treasury; this afforded lower interest rates and less stringent policy strictures than going through the World Bank.

To understand who Mann was and what he did in Latin America, one only has to comprehend that in reviewing the Alliance for Progress, historians like Schlesinger and LaFeber divide it in half: the Kennedy version versus the Johnson version. As Alliance administrator William D. Rogers stated about the Mann/LBJ takeover: “… a more dramatic shift in tone and style of US Alliance Leadership would have been difficult to imagine.” (Schlesinger, p. 721) As for President Kennedy’s oratorical hopes for the Alliance causing peaceful revolution, LBJ assistant Harry McPherson termed that: “A lot of crap.” As LaFeber notes, the Mann/LBJ revision of the Alliance consisted largely of dismantling it. But also in tilting it away from economic investment and toward military build ups. (LaFeber, p. 156) As Juan Bosch later noted of JFK’s intent to use the Alliance for Progress for democratization and structural change, those aims died with Kennedy in Dallas. (Schlesinger, p. 722) Bobby Kennedy predicted what the outcome of that abandonment would be: “The people of Latin America will not accept this kind of existence for the next generation. We would not, they will not. There will be changes.” Considering the violence that swept through Central America in the eighties, and the more peaceful revolutions that occurred in the new millennium, Kennedy was correct. (For the latter, see Oliver Stone’s documentary film, South of the Border.)

A significant achievement of the book is its detailed explication of Robert Kennedy’s opposition to what LBJ did in another theater of Third World conflict, South Vietnam. The accepted version of RFK’s thoughts and actions on this subject has been that his tacit acceptance of what Johnson did in Indochina from 1964-66 suggested that he was in agreement with it. With what Bohrer has unearthed for his book, that view is simply untenable today.

When young Adam Walinsky first joined Senator Kennedy’s staff, Kennedy told him that Johnson was more conservative than most people thought he was. (Bohrer, p. 141) Walinsky recommended that they not confront Johnson directly, but on the edges of policy, thus not inciting an open feud. So Kennedy took his time in making his disagreement over Indochina public. But as early as 1964, he told Johnson that he did not think the war should be escalated into a full-blown military conflict. (p. 70) Kennedy felt that raising the military component to a higher level would not work. There had to be some attempt at a political settlement. But also, our side had to offer more significant aid to the people of South Vietnam. Johnson feigned at agreeing with this approach. But, as we all know, that is not the path he took. (p. 152) In June of 1964, shortly after telling Johnson about his ideas, Attorney General Kennedy confided to Schlesinger that he believed “the situation in Vietnam may get worse and become a serious political liability to the administration.” (p. 72)

It did get worse after the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was passed two months later, and Johnson began air attacks against the north. When the Viet Cong retaliated by detonating bombs on new American air bases, the retaliatory air attacks increased. Kennedy was also disappointed that, while escalating, Johnson seemed to rely for advice and courage on former President Eisenhower. (p. 152)

Journalist David Halberstam—who was a full-fledged Hawk at the time—got wind of this and criticized Bobby on the grounds of arrogance: How dare he think he was smarter than the likes of LBJ and Eisenhower? Unlike them, Bobby thought he could win the war without dropping tons of bombs and using overwhelming force. Needless to say, Halberstam’s half-baked ideas would lead to an epochal disaster. And only when it peaked out in 1968, with over 500,000 combat troops in Vietnam, and the war devolved into ”dropping tons of bombs and using overwhelming force,” did Halberstam begin to see that he and his colleague Neil Sheehan were utterly and completely wrong about a path to victory. But, to my knowledge, neither author ever admitted that the Kennedys were right.

III

Although some members of JFK’s staff wanted to resign after his assassination, the Attorney General advised them to stay on at least until the presidential election of 1964, if only in order to push Johnson into following through on President Kennedy’s goals on civil rights, unemployment insurance, and aid to education. In January of 1964, there was a boomlet to draft Bobby Kennedy as Johnson’s vice-president. Democratic leaders like Peter Crotty of New York, and Paul Corbin, who was working a write-in vote for Bobby in New Hampshire, were a major part of this effort. (Bohrer, pp. 31-39) Without visiting the state, Kennedy got over 25,000 write-in votes in New Hampshire. (p. 47) By April, a poll showed that 47% of the public wanted the Attorney General to serve as vice-president. An aide, Fred Dutton, advised him to make more speaking engagements to boost that figure. Up until that time, Kennedy had only made two speeches after his brother’s death. The first was little more than a courtesy appearance for the UAW, the second was a speech on civil rights. Kennedy now began to negotiate personally with GOP Senator Everett Dirksen over the civil rights bill in progress through Congress. (p. 55) To show how intent he was on seeing the bill pass, he visited Prince Edward County Virginia, a school district that had closed down its school system rather then integrate. The Kennedys had been instrumental in raising private funds to keep the system open. RFK visited the area again to present a large check to the Teachers’ Union to sustain issuing paychecks. Shortly after, in a visit to West Georgia College, he was asked about George Wallace’s popularity. He replied that people who vote for Wallace “…want the Negroes to be quiet, but the Negroes are not going to be quiet.” He then managed to continue his reply with what was now becoming his favorite word: “This is a revolution going on in connection with civil rights and the Negroes.” (pp. 58-59)

In an oral history given as he began to find his own voice, Kennedy stated the differences between him and the new president. He said LBJ had made it clear that it was not really the Democratic Party anymore. It was now an All-American party and the businessmen like it. All the people who opposed JFK now like it. He concluded with, “I don’t like it much.” (p. 60)

Those sentiments are remarkably consistent with what Senator William Fulbright would conclude in 1966 as he began to investigate the reasons for the escalation in Vietnam. Namely, conservatives opposed to President Kennedy were now supporting LBJ, while liberals who supported President Kennedy were now opposed to the new president. In the late spring of 1964, Bobby Kennedy began to formulate a countering political strategy: running for the Senate from New York. As he said, there he would be the “head of the Kennedy wing of the Democratic Party.” (p. 60)

Bobby Kennedy was leaving the Senate seat in Massachusetts to his brother Teddy. His brother-in-law, Steve Smith, had been at work organizing President Kennedy’s presidential campaign. New York was to be a big part of that campaign. So Smith now switched to recommending RFK run for the Senate in New York against Republican Kenneth Keating. After all, the Attorney General had lived in New York for about ten years. (pp. 62-63) Bobby now put out the word that he would resign from Johnson’s cabinet after the civil rights bill was passed and signed. As the author notes, one of the things that bothered the AG was that he believed that Johnson saw Vietnam as a military problem. Kennedy did not see it that way. He thought a purely military effort would not be successful. He also did not like Secretary of State Dean Rusk, who was also a Hawk on Vietnam. (pp. 70-71) Because of this, Kennedy was not happy when Johnson chose General Maxwell Taylor as the new ambassador to Vietnam. RFK liked Taylor because of his advocacy of low intensity warfare through Special Forces, like the Green Berets. But Kennedy thought that LBJ chose the general to give him cover for a military escalation. Which turned out to be the case. (p. 74)

The civil rights bill passed in the latter part of June, 1964. A few days later, Ben Bradlee of Newsweek asked Kennedy what he would like to do in life now. Kennedy replied that he would like to maintain all the energy and excitement his brother had generated and harness it. (p. 88) Bradlee printed this and Johnson was quite naturally perturbed. During the signing of the bill, LBJ let Bobby know how perturbed he was. Within earshot, he handed a signing pen to J. Edgar Hoover and told the FBI Director, “You deserve several of these.” If anything told the Attorney General he was persona non grata with the new power axis, that did. (p. 90) Further, Johnson now arranged the upcoming Democratic convention so that the salute to President Kennedy came on the last night, instead of the first. Johnson was worried because Bobby Kennedy was now outpolling Hubert Humphrey for vice president by a margin of 2-1. In July, Johnson called in the Attorney General and read off a list of potential vice presidential nominees he would not consider, with Bobby being on the list. (p. 100) The next month in Atlantic City at the Democratic convention, it was obvious that Johnson had made the right decision for himself politically. When Robert Kennedy appeared at the podium an oceanic ovation took place that lasted over ten minutes. In the public eye, Robert Kennedy was the heir apparent to his brother. It was time to begin his ascension to the throne.

IV

Robert Kennedy declared himself a candidate for the Senate on August 25, 1964 at his home in Glen Cove, Long Island. As he began to campaign, something unusual began to happen which no one recalled seeing before. In his public appearances, a reaction set in similar to Beatlemania: people began to tear his clothes off, rip his cuff links, and shake hands with him so hard that after doing this repeatedly, it caused the candidate’s hands to bleed. (p. 117) His managers, fearing for his health, demanded he not campaign each day and take off one day per week to recover.

His advisors also found out that Kennedy did not speak well in rehearsed commercials for the camera. But he did do well in unrehearsed Q-and-A periods after delivering a speech, especially with young people. So this is what they broadcast. (p. 124) Kennedy ended up defeating Keating by ten points.

Once in the Senate, RFK visited his brother’s grave at night. In fact, after a friend watched this happen once, he realized that the groundskeeper had an arrangement with Bobby to let him in when no one was there. (p. 147) In the Senate, Robert Kennedy decided to do what he could to maintain what he perceived to be his brother’s legacy. He fought against closing Veterans Hospitals for budgetary reasons. He got the administration’s requested allotment cut in half. He moved for adding testing provisions to a large education bill—and he got that through. He fought Governor Nelson Rockefeller on getting grants for New York state’s impacted poverty areas. He won that battle also. (pp. 148-50) By his eleventh week in office, the new senator was getting a thousand letters per day.

One of his pet issues was something his brother was an early advocate for: gaining home rule for Washington D. C. He said about this objective that, because the District of Columbia was predominantly African-American, home rule was being held back for the reason that “there are many people who don’t want progress made here.” (p. 161) He further added that, in his view, the problem fundamentally was not about race, but about poverty. There was a reason he accentuated this point. RFK had kept his notebook from President Kennedy’s last cabinet meeting. In his notes he had written down the word “poverty” seven times. So this was another way of continuing the policies his older brother had left behind. (p. 159) To him, if America did not attack the problems of broken homes in the ghetto, and the effect that had on education, then there would be no real improvement.

RFK and his brother Senator Ted Kennedy were very much involved in extending the Civil Rights Act with the Voting Rights Act of 1965. They also wanted to add a clause that would eliminate the poll tax. That failed, and an amendment had to be passed to eradicate the tax. (pp. 165-66) The bill passed in large part because of the 1964 electoral landslide, which gave the Democrats 68 seats in the Senate. As Walinsky later said, it was, “A crazy time. I mean we were going to reshape American society, all of us. There was a new bill every day.” (p. 166)

But there was a shadow hanging over it all. In early April of 1965, Johnson gave a hawkish speech about Vietnam. This was just after the first combat troops had landed at DaNang Air Base, and Rolling Thunder, Johnson’s air campaign against the north, was in its initial stages. Again, RFK advised Johnson against taking the militaristic path in Vietnam. Sounding like his fallen brother, he added that America should make it clear to the Saigon government that we will not be staying there to fight the war for them. He even asked Johnson to fire Dean Rusk and replace him with the more moderate Bill Moyers. (p. 168) But since he was a Democrat, and American troops had been committed into theater, he also felt obligated to vote for Johnson’s appropriations for escalation, even though he did not approve of the actions. He explained, “If I voted for it without saying anything, it would have appeared that I approved of it—which I didn’t.” (p. 175)

In his public speeches he again returned to his favorite word, revolution. He praised students who marched on Washington as demonstrating the “essence of the American Revolution.” (p. 180) At a commencement address he stated, “We are the heirs of a revolution that lit the imagination of all those who seek a better life for themselves and their children.” He added that there was also a revolution aimed against America. After hundreds of years of domination by the West he said, America buys 8 million cars per year, while those in formerly colonized countries go without shoes. He told the graduates, that they “have an unparalleled opportunity—not to find a world, but to make one.” (p. 179)

Kennedy had no qualms about taking on big lobbies or big business. He railed in public about the growing power of the NRA, a lobby which he characterized as spending huge amounts of cash distorting the facts, and which placed a minimal inconvenience above saving the lives of thousands of Americans each year. (p. 182) He called in the CEO’s of the Big Three auto companies and questioned them about how much money their companies were making while spending so little on research into safety matters. (pp. 200-01) He also moved against the tobacco companies. He was the first to propose a warning label on cigarette packages. (p. 203) Senator Kennedy even tried to get right-to-work statutes repealed. These were laws, mostly in the south, that weakened unions since they allowed employees in a shop to opt out of union membership while enjoying union benefits. (p. 203)

Reading Bohrer’s book, it is very hard to defend the MSM meme that RFK was a reluctant warrior on civil rights and the plight of African Americans. For the simple reason that he never let go of the issue. At times he went beyond what most civil rights advocates were talking about. Frequently, his ideas echoed Martin Luther King’s. At a VISTA indoctrination in Harlem, Kennedy said, “It is one thing to assure a man the legal right to eat in a restaurant: it is another thing to assure that he can earn the money to eat there…” (p. 205) He was sometimes at pains to delineate the differences for black Americans in the south versus the north. For example, he stated, “Civil rights leaders cannot, with sit-ins, change the fact that adults are illiterate. Marches do not create jobs for their children.” (p. 205)

In one of his most controversial statements about the issue, the former Attorney General talked about the differing ways in which the law is looked upon by middle class and wealthy Caucasians as opposed to downtrodden minorities. To the more privileged group, the law is looked upon as a friend who preserves and protects property and personal safety. But to the latter group, the law seems different: “The law does not fully protect their lives, their dignity, or encourage their hope and trust for the future.” (p. 206) Kennedy was attacked for this statement by several media outlets including the Christian Science Monitor, the New York Times and Time. They characterized his comments as a sitting senator encouraging youths to break the law. Kennedy stood by his statement. He said that the Watts riots of 1965 would be repeated “across the nation if we don’t act quickly.” (p. 206)

As noted above, another point that Bohrer’s book effectively contravenes is the idea that Kennedy was late to oppose Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. As shown, Kennedy had done this in private with LBJ in 1964. That same year, in an address at Caltech, he did so publicly in an indirect way. He stated that guerilla warfare and terrorism arose from the conditions desperate people live under, and they cannot be put down by force alone. He then said, “Over the years, an understanding of what America really stands for is going to count far more than missiles, aircraft carriers and supersonic bombers.” (p. 190)

What surprised many commentators inside the beltway was that the first term senator’s attempt to forge his Kennedy wing of the Democratic Party was working. For example, one evening there were two competing Washington social events arranged. One was by the Kennedys; one by the wealthy Washington hostess and former ambassador to Luxembourg, Perle Mesta. Mesta had backed Johnson against JFK in 1960. The Kennedy gathering outdrew Mesta’s by a 10-1 ratio. (p. 183)

In the midst of this entire rising furor came the invitation to speak in South Africa.

V

Ian Robertson was a member, and eventual president, of the longstanding National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). From its founding in 1924, this group had opposed the apartheid system in their country. In July of 1965, Robertson extended an invitation to Kennedy to speak at Cape Town University in the spring of 1966. After doing so, he challenged the authorities to deny Kennedy entry. Robertson was now placed under house arrest. Not only did Kennedy accept, he made the invitation public, thereby making it harder for the South African government to deny him entry. Reporter Murray Kempton wrote, “It is unlikely he will ever go. What is extraordinary is the fact of the invitation …. Senator Kennedy has a name at which lonely men grasp in their loneliness.” (p. 227)

Kempton was wrong. Kennedy had every intention of speaking in South Africa. But at the time that journey was being arranged, RFK also decided to also take an expedition to Latin America. What Kennedy did south of the border, and the very fact that he was determined to go to South Africa—these factors defined who he was at this time, and also where he was in the makeup of our political system. As we shall see, he had by now clearly inherited his brother’s mantle, and in some ways, gone beyond it.

Before going to Latin America, Kennedy was to be briefed on the political conditions in the countries he was visiting, and also what the State Department wanted him to say and not say while he was there. So he and two assistants showed up at the State Department and were briefed by Jack Vaughn. As Vaughn went through the countries Kennedy was to visit, and advised him on what to say if anyone asked him about the American invasion of the Dominican Republic, the senator began to fully understand how much Johnson had overturned President Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress program. By the time it was ending, RFK registered his disgust at what had happened:

Well, Mr. Vaughn, as I see it, then, what the Alliance for Progress has come down to is that you can abolish political parties and close down the Congress and take away the basic freedoms of the people and deny your political opponents any rights at all and banish them from the country, and you’ll get a lot of our money. But if you mess around with an American oil company, we’ll cut you off without a penny. Is that it?

Vaughn then replied, “That’s about the size of it.” Walking out of the meeting, Kennedy said to one of his assistants, “It sounds like we’re working for United Fruit again.” (p. 231)

What Kennedy said and did while on this voyage south seemed designed to show that he, for one, was not working for United Fruit. In addressing crowds in Lima, Peru, he told them to emulate the men who liberated Latin America from the Spanish Empire: San Martín and O’Higgins. He urged them on by saying, “You can do as they can. You cannot do less.” He then went beyond that. He urged them to emulate the justice of their Indian ancestors, the Incas, who punished nobles more harshly than they did the peasants for breaking identical laws. (p. 233) In Lima, Santiago and Buenos Aires, he repeated what had become his motto: “The responsibility of our times is nothing less than revolution.” (p. 233)

In speaking of the history of the United States, he told crowds that the revolution in the American political system that they should look at was Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Because that example demonstrated “the power of affirmative free government.” To RFK it was a hallmark of the state combining the twin ideals of social justice and liberty. (p. 234)

In Peru, Kennedy made part of his itinerary a visit to the high altitude city of Cuzco, the capital of the Inca civilization. There, young children followed him shouting “Viva Kennedy”, ripping his pants and tearing his cheek, drawing blood. On their way back down, he stopped to talk to some peasant farmers tilling the land. When they told him they paid high prices for powdered milk donated through the US Food for Peace program, he turned to the Peace Corps aide with them and told him to look into the matter. He then asked aloud, “What happened to all our AID money? Where is it going?” He then added that the ambassador to Peru, Wesley Jones, “might as well have been the ambassador from Standard Oil.” (p. 235)

The high point of the Peru part of the visit was a meeting with intellectuals and artists in Lima, at a gathering that resembled a salon on the west side of Manhattan. Bobby was being assailed about all the problems that the Rockefeller owned oil companies had caused and mistakes America had made. RFK asked why they always looked to the USA first. The answer was that the USA would not let them do anything about Rockefeller’s International Petroleum Company. Kennedy replied that they could not have it both ways, cursing the USA and then blaming the State Department. The solution was simple: nationalize the oil company. Someone responded that David Rockefeller had been there and warned them if they did anything to his oil company all aid would be cut off.

The senator’s response to this should serve as a model to any doctrinaire leftist who still thinks that the Kennedys were part of the Eastern Establishment. He tartly replied, “Oh, come on! David Rockefeller isn’t the government. We Kennedys eat Rockefellers for breakfast.” (p. 235)

In Chile, he offered to debate with communist students on an equal time basis. But after he gave his speech and offered the time to the other side, no one took him up on it. (p. 240) Then, in the mining town of Concepcion, he went down into a coal mine. When he came back up he said, “If I worked in this mine, I’d be a communist too.”

In Brazil, three youths were arrested on charges of plotting to kill the senator. Bobby asked that they be released. They were not, but the charges were then lessened. RFK then sent a messenger to the jail to ask them to write down any questions they had about him. (p. 244) He then visited a sugar cane field and talked to the workers. They told him that their landlord was paying them three days wages for six days work. The senator walked directly to the property owner’s house and started yelling at him for not paying his workers a decent wage. (p. 245) He then went to the presidential palace. After visiting with the newly installed government ushered in by the previous year’s CIA sponsored coup, he was being driven back to his hotel when he saw some of the crowd being struck by soldiers trying to keep them away from his car. He jumped out of the car and shouted, “Down with the government! On to the palace!”

His visit to Latin America was so incendiary that much of it was not reported in American newspapers. (p. 245)

VI

At the time of his death in August of 1965, United Nations representative Adlai Stevenson was working on at least one—perhaps two—ways of negotiating out of Vietnam. One was through the UN Secretary General U Thant. A second rumored one was initiated by Ho Chi Minh, using Italy and India as go-betweens. (p. 250) Bobby Kennedy heard about these through his contacts in the White House. He was very disappointed they came to naught, and shared his chagrin with columnist Joe Kraft. Kraft then wrote a column in which he said that the senator opposed what Johnson was doing in Indochina, but could not confront the White House about it out of loyalty to the president and also to his party.

In December of 1965, echoing Martin Luther King, Kennedy said that we should not forsake the domestic battle against poverty for a war abroad because it would divide the nation. (p. 252) Heeding Kennedy’s words to accept an offer for a bombing halt at Christmas 1965, Johnson did so, although he told Defense Secretary Robert McNamara it went against his “natural inclinations.” Both Senators Fulbright and Kennedy urged Johnson to use the interim halt as a negotiating tool for some kind of settlement. When LBJ resumed bombing at the end of January 1966, Kennedy said if bombing Indochina is our answer to the problem there, we were headed for a disaster. He added that, “The danger is that the decision to resume may become the first in a series of steps on a road from which there is no turning back—a road which leads to catastrophe for all mankind.” (p. 264)

The next month RFK called a press conference. The reaction to this conference shows just how much Johnson and the unquestioning press—specifically David Halberstam and Neil Sheehan—had tilted the scales toward intervention. This press conference was called a few months after Halberstam had published his book, The Making of Quagmire. That book was an all out attack on American policy toward Saigon from the right. Kennedy suggested a power sharing coalition government in South Vietnam, which included the communists. (p. 269) In retrospect, this was a very sensible solution for everyone: Hanoi, Saigon, and the USA. Kennedy was viciously attacked by both the MSM and Washington politicians, even those from his own party. Vice-President Humphrey said this would be like placing an arsonist in the fire department. The Chicago Tribune called him Ho Chi Kennedy. Forgetting Vietnam was one country, The Washington Post said it would be rewarding aggression. (pp. 271-74).

Incredibly, Kennedy visited both Ole Miss and the University of Alabama in 1966. At Ole Miss, he revealed to the crowd just how politically motivated Governor Ross Barnett was before the James Meredith riot broke out there in 1962. In negotiations with Barnett, the governor had asked Kennedy if he could have a federal marshal pull a gun on him so it would look like he was physically intimidated into going along with integrating the college. Kennedy was not responsive. So Barnett called him back and said, no, he wanted all the marshals to pull guns on him. The students roared with laughter at that one. (p. 285)

At Christmas, 1965, Kennedy threw a series of celebrations of the holidays in the Bedford Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn. It was his way to begin to follow through on President Kennedy’s nascent attempt at a war on poverty. It was his way to generate interest in a developing program to attack the poverty cycle in the inner cities. He gave a series of three speeches on the subject. The aim was to break up the ghettoes and offer subsidies to those who wished to leave. For those who stayed, Kennedy wanted to give more aid to schools to improve education, offer tax breaks to companies to relocate there, and free legal advice for tenants to fight predatory landlords. The idea was to go beyond the New Deal. He envisioned this program to be a combination public-private community development corporation, the aim being to offer a diversified program to end inner city poverty and eradicate ghettoes. (pp. 255-61)

There can be no better way to end this review than to describe Kennedy’s eventual journey to South Africa at the request of the courageous Ian Robertson. I should preface this by saying Kennedy really had nothing to gain from this visit. The South Africa cause was so vague and nebulous in 1966 it did not even register as a blip on the political screen. And, due to what he and his brother had done from 1961-63, there was no domestic political benefit for him because he already had the African–American vote tied up.

The South African government denied any American reporters entry into the country. Four who tried to sneak in were rounded up and placed on a plane to Rhodesia. (p. 294) The visual record we have of this momentous event consists largely of grainy black and white home movies. No member of the government would meet with him. And the only press representatives on hand were those who supported apartheid. Unlike in the USA and Latin America, spectators did not rush to grab him, since it was considered an offense for a black man to shake hands with a white man. At his first speaking engagement Kennedy stood an empty chair next to him to signify the absence of Robertson. Robertson had been charged with the Suppression of Communism Act. Which evidently meant that, in South Africa, RFK was considered a communist.

When he visited Robertson at his apartment, the government would allow no one else to be present, not even friendly journalists. The first thing he asked Robertson was if the place was bugged. He then told him to stomp his feet to throw the surveillance off temporarily. Kennedy then asked him questions about his country and how he felt about Vietnam. He told him how badly he felt about his house arrest. He closed the meeting by giving him a copy of President Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage. It was signed by Jackie Kennedy. (p. 295)

He then went to make his memorable speech at the University of Cape Town—to, of course, an all white audience. That speech has one of the most brilliant openings in the history of modern American oratory. He began by saying he was glad to be in a country settled by the Dutch, taken over by the British, and now a republic. A nation in which the natives had been subdued and with whom relations remained problematic; a land which defined itself by a hostile frontier; a land which once imported slaves and now had to solve the residue of that problem. He then stopped, smiled, and said, “I refer, of course, to the United States of America.” (p. 295)

He then talked about the responsibilities of a republic, which South Africa had become in 1961. And how that model of government was intended to guarantee individual rights for its citizens. He added that he meant all of the citizenry. He then talked about governments that denied freedom and would label as “‘communist’ every threat to their people.” He continued with how his family had felt the sting of prejudice because they were looked down upon as being Irish in New England. He mentioned the fact that Martin Luther King had won the Nobel Prize because of his struggle in the USA. He ended his speech in South Africa with the following:

Each time a man stands up for an ideal or acts to improve the lot of others or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

He then closed with, “Each of us have our own work to do.”

This is a fine book. The best volume on Robert Kennedy I have read since Arthur Schlesinger’s two volume set in 1978. If you want to know about Bobby Kennedy’s life, the Schlesinger book is your choice. But if you want to know who RFK was in his last years, this is the book to read. No politician I know of ever did or said these kinds of things at home and abroad. I strongly recommend the book as a Christmas gift for your children and younger loved ones. Through it, they will be reminded that, not that long ago, the political spectrum was not defined by the likes of Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. And you did not have to hold your nose before entering the voting both. We all owe thanks to John Bohrer. He is to be congratulated for capturing the essence of a good man who became a great man. The vivid memory this book draws reminds all of us just what America could have been.