One of the worst instances of the media’s obeisance to the Powers That Be concerning the JFK case occurred upon the issuance of the Warren Report. If the reader will recall, this happened in late September of 1964. The report was handed to President Lyndon Johnson on Thursday, September 24. There was an official photograph taken on that day in the Oval Office. All seven commissioners, plus Chief Counsel J. Lee Rankin, were pictured. Chief Justice Earl Warren handed LBJ the 888-page report. This was, for all intents and purposes, a photo op, as the report was not released to the public until Sunday evening, the 27th.

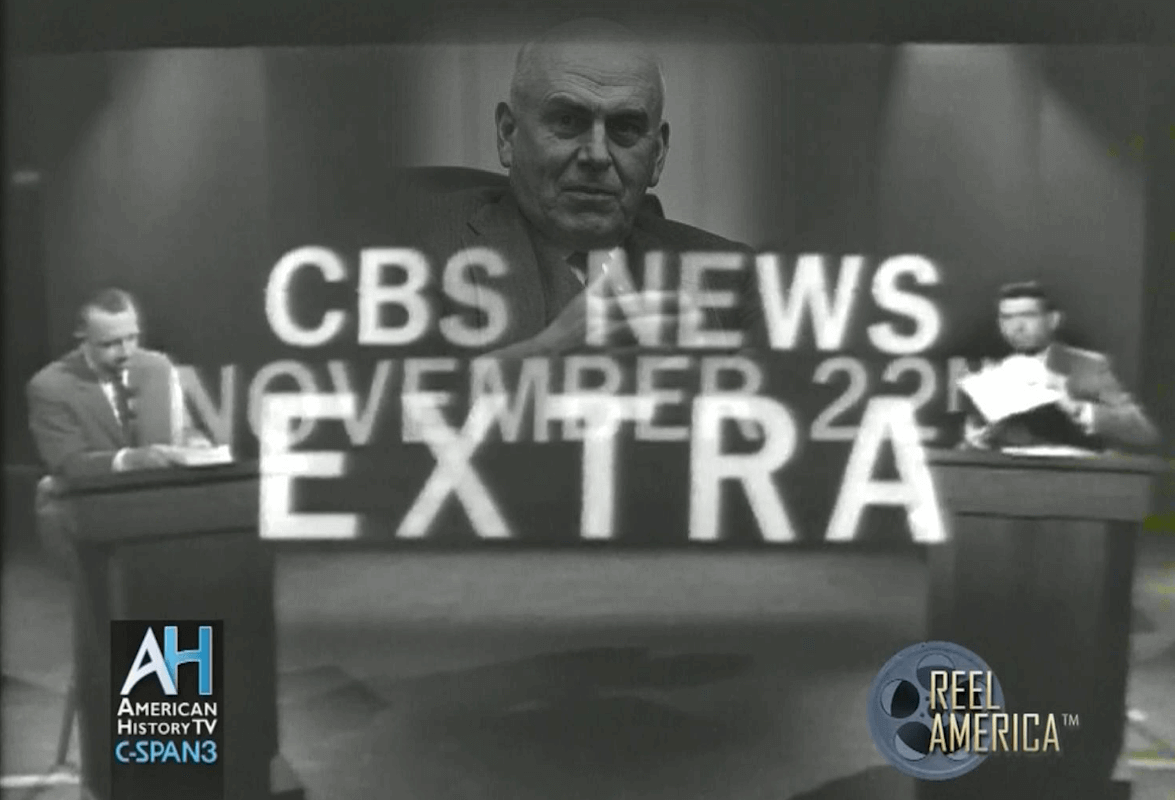

A funny thing happened that Sunday evening. Both the CBS and NBC networks broadcast specials on the JFK case. Both were based upon, and endorsed, the Warren Report. This was odd in two respects. First, how could anyone have read the quite lengthy and complicated report that fast? What makes that even harder to understand is that the Warren Commission worked in almost complete secrecy. Their hearings were closed to the press and the public. The only exceptions among the approximately 500 witnesses the Commission itself interviewed were the two depositions of Mark Lane. They were excepted for the simple reason that Lane insisted his appearances be done in the open. (Walt Brown, The Warren Omission, p. 244)

As author Seth Kantor notes, inside the Commission itself, the working staff of attorneys was pretty much kept away from the seven commissioners and the chief counsel. (Seth Kantor, The Ruby Cover-Up, p. 163) This information above leads to the conclusion that the two broadcast programs were produced by directed leaks from the top level of the Warren Commission. The only other logical possibility would be that they were done with the help of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, since he did the great majority of the investigative work for the Commission.

It was very soon discovered that, although the Warren Commission tried to label itself a fact-finding committee, that rubric is not really accurate. After one studies their deliberations, their conduct of interviews, and their methods of investigation, it is quite obvious that there were significant holes in their fact-finding quest; for instance: Oswald in New Orleans, Oswald in Mexico City, Kennedy’s autopsy, Jack Ruby’s entry into the Dallas Police basement. But even with their foreclosed database, the Commission clearly produced a prosecutor’s brief. (Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment, p. 378) For two reasons, that end result was almost inescapable. First, the Commission decided that Oswald had been the lone gunman before they interviewed their first witness. (Lane, pp. 365-66) Secondly, the Commission refused to grant Marguerite Oswald the right to appoint a counsel to represent her deceased son’s interests. (Lane, p. 9) On the issue of fairness to the alleged assassin, the Commission tried to cover itself by saying that they had enlisted the services of one Walter Craig, the president of the American Bar Association, to find if the “proceedings conformed to the basic principles of American Justice.” (Sylvia Meagher, Accessories After the Fact, p. xxix) Craig only attended hearings from February 27 to March 12, 1964. Any suggestion he made in deference to Oswald’s rights is not visible in the record. As Sylvia Meagher concluded in this regard, “The whole sorry arrangement was a mockery that further compromised the Commission’s claim to impartiality.” (p. xxix)

What is so fascinating in reading and viewing the immediate endorsement of the MSM upon issuance of the report is that none of the commentators even mentions this large lacunae in the Commission’s procedure. As any attorney will state, the whole basis of the American justice system is the adversary procedure. One of the fulcrums of that adversary procedure is the cross-examination of witnesses, the right to examine documents, the right to make objections, etc. Even in fact-finding procedures done for Congress (e.g., Watergate or Iran/Contra), there was a majority and minority counsel, so one gets something resembling an adversary procedure. To put it mildly, that did not happen with the Warren Commission. But somehow, in their eagerness to embrace the official story, the press ignored this issue with a completeness that is almost astonishing. It is made even worse by the fact that the reporter who did the immediate endorsement for the New York Times, Anthony Lewis, had just written a best-selling book on the subject. Lewis’ book was called Gideon’s Trumpet. It was about the 1963 Gideon v. Wainwright Supreme Court case. In that case, the court ruled that defendants in criminal cases must be supplied an attorney even if they could not afford one. How Lewis could turn his back on his own book is puzzling.

The press did not just accept the Warren Report, it did not just embrace it, but as the evidence above indicates, they colluded with its creators to present it to the public as the ultimate truth about the murder of President Kennedy. Near the end of the 1964 CBS special, Walter Cronkite goes so far overboard in this regard that today it is almost embarrassing to view. Cronkite says that it is hard to imagine a more thorough inquiry could have been done, and that Oswald lied about every major point he was questioned on.

What makes these pronouncements patently absurd is the fact that the 26 volumes of testimony and evidence the Warren Report based their conclusions on would not be published for two months: that is, November 23, 1964. Those volumes contained over 17,000 pages to inspect. With that paradox, we are left with two alternatives to ponder. Either someone on the Commission leaked both the report and its evidentiary volumes to the media, or someone associated with the inquiry gave them advance summaries of what that evidence would say. I should not have to add the serious journalistic problem in this collusion. As demonstrated above, the Commission was extremely biased in their presentation. They would not even allow a representative for Oswald. Since they worked in secret, there was no way to cross check their procedures or methodologies. So to accept at face value the Commission’s presentation was a huge gamble. People like Cronkite and Lewis risked losing the trust of the public in both the government and the media if they were wrong.

The CBS special that was broadcast on the night of September 27 was longer than the NBC rendition. It ran for two hours. The producers interviewed a number of witnesses who the Commission relied upon for its guilty verdict: Ruth Paine, Marina Oswald, Howard Brennan, and so forth. The story about how Brennan was included on the CBS special bears mentioning. At first, he was not going to appear. This probably owes to the fact that there was a debate inside the Commission as to whether or not the man was credible, or whether his liabilities outweighed his probative value. (Edward Epstein, Inquest, p. 136) When CBS first announced its schedule of over twenty witnesses, Brennan was not included. But when the Commissioners decided that Brennan was necessary, the CBS script was revised and Brennan was sent to New York to be interviewed before the program’s deadline. This is how close the ties were between CBS and the Commission. (Mark Lane, A Citizen’s Dissent, pp. 77-78)

In 1964, Emile de Antonio had released a cinema-vérité-style documentary about the fall of Senator Joseph McCarthy. For Point of Order de Antonio relied largely on film from the CBS kinescope archives. (Lane, A Citizen’s Dissent, p. 75) In 1966, de Antonio was working with Mark Lane on a documentary about the Kennedy assassination. It would eventually take the same title as Lane’s book, Rush to Judgment. The director got in contact with the CBS library and proposed to repeat the process of purchasing film from that network. The response from librarian Virginia Dillard was positive. (Washington Journalism Review, Sept-Oct, 1978, article by Florence Graves; hereafter referred to as Graves in WJR) Lane and de Antonio arranged to go to the CBS archives after hours and sit in front of a movieola to view the outtakes from that 1964 production.

As Lane writes in A Citizen’s Dissent, he and de Antonio were unprepared for the interviewing techniques they saw being used. If a witness was asked where he thought the shots came from and answered with “the knoll area”, the interview was halted. There was an interim that was not accounted for and now the witness would reply that although he originally thought the shots came from the knoll, he now thought they came from the Texas School Book Depository. On the third take, the witness would be asked where he thought the shots came from and he would reply, the depository building. This would be presented as the interviewee’s answer. (Lane, A Citizen’s Dissent, p. 78)

De Antonio described the same pattern in an interview he did for journalist Florence Graves in 1978. He said that what he recalled was people in these outtakes saying things that did not get on the program since they contradicted the official story. He then said that it was clear that the interviewer was leading the subjects to a predetermined conclusion. He summed it up with, “The interviewer was more like a prosecuting attorney leading a witness to support the state’s case.” In other words, CBS not only served as an outlet for the Commission, they even did their dirty work for them. (Graves in WJR)

Lane and de Antonio now ordered up the outtakes they wished to use. But the next day Dillard told them the deal was cancelled. She said that CBS never sold outtakes. (Graves in WJR) This, of course, was pure malarkey. They had done so with Point of Order, and they had just agreed to do so in the JFK case. This reversal must have come down from the executive suites at the network. Either Dillard or the movieola operator had informed them what was happening. Someone like CBS president Richard Salant then overruled the Dillard agreement and the previous de Antonio precedent. The Kennedy case was that important.

In the 1978 Florence Graves article, it is revealed that one of the producers of the 1964 CBS program, Bernard Birnbaum, admitted there were leaks from the Commission for that special. He added that some of the interviews went on for as long as an hour. But further, and perhaps most importantly, he said the production was months in the making.

Why did Graves write her piece in 1978, 14 years after the original special aired? Because in the fall of that year, there was a controversy in the press about whether or not the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) had tried to secure these important pieces of film that had been denied to Lane and de Antonio. The Washington Post reported at the time that the HSCA had not tried to secure the 70 hours of film that CBS still had. (Washington Post, 9/17/78, report by Larry Kramer) And they used Robert Blakey, chief counsel of the HSCA, as their source. That article quoted witnesses landlady Earlene Roberts and cab driver William Whaley as saying things to CBS that contradicted what was reported by the Commission. The Post reporter speculated, as did Graves, that what the witnesses said could back up the concept of a Second Oswald, an idea that some critics had postulated as far back as 1966.

For the Post article, the pretense that Salant was using to keep the outtakes away from Lane, de Antonio and the HSCA evolved into comparing the film with an investigative reporter’s notes. Which is hard to comprehend. The latter is tied in with the whole idea of a reporter’s need to keep certain sources secret in order to develop information that would benefit the public. Usually, arrangements are made prior to the interview about these special circumstances. Nothing like that would exist in the CBS example. Birnbaum told Graves that the only guarantee he made to the witnesses was the broadcast would not be aired until the Warren Report had been released. Also, why could a witness agree to go on camera if there was anything dealing with personal secrecy involved? In the CBS case, clearly, the value of the transmittal would greatly outweigh the value of keeping the information secret. Or as de Antonio said to Graves for the WJR article, “Does CBS have an Official Secrets Act like the CIA? What is it afraid of?... What is CBS hiding? I won’t guess.”

For the Graves article, Salant contradicts what Blakey said about the matter. Salant told her that the HSCA did make such a request for all film, including outtakes, in both the JFK and Martin Luther King cases. This was done both orally and in writing. Graves found out from other sources that the HSCA did want the outtakes but CBS would not surrender them. Realizing that this would be a long legal battle that would detract from the investigation, the Committee decided not to issue a subpoena.

As this site had explored before, CBS was and is one of the worst media agencies to ever broadcast on the assassination of President Kennedy. Through former employee Roger Feinman, we showed that the upper level of management vetoed and then reversed the desire of the reporters and lower managers to honestly investigate the JFK case in their 1967 four night special. In that article we intricately demonstrated how the CBS cover-up of the facts worked and how it pervaded that special. We also showed how CBS then denied that it had done the things it did, such as employing Warren Commissioner John McCloy as a secret advisor to the program. Based on Feinman’s inside information, plus the testimony of Lane and de Antonio, it is not unwarranted to suspect the worst about 1964, and Salant’s refusal to admit it in 1978. After all, Salant refused to admit the role of McCloy in the 1967 special as late as 1977, just one year before the Graves article appeared. Salant finally did admit to the McCloy role in 1992 when Jerry Policoff confronted him with written evidence of the memos McCloy wrote. (Go here for that story) In other words, Salant covered up what he knew to be true for 25 years about what McCloy had done in 1967.

With that record, who would believe his protestations in 1978 about what had happened in 1964?

(The author would like to thank Bart Kamp and Malcolm Blunt for the sources used in this piece.)