The following interview was recorded on December 21, 1966 at the studio of Pacifica outlet KPFK in Los Angeles. Harold Weisberg discusses the dubiousness of two key witnesses for the Warren Commission: Howard Brennan and policeman Marrion Baker. Both are key for the Commission. Brennan is the sole witness who places Oswald in the sixth floor window, and Baker says he encountered Oswald in the second floor lunchroom after the shooting. It should be noted, Weisberg is alone among the early critics in questioning Baker’s story since he somehow had Baker’s first day affidavit, where he makes no mention of a second floor lunchroom.

O’Connell:

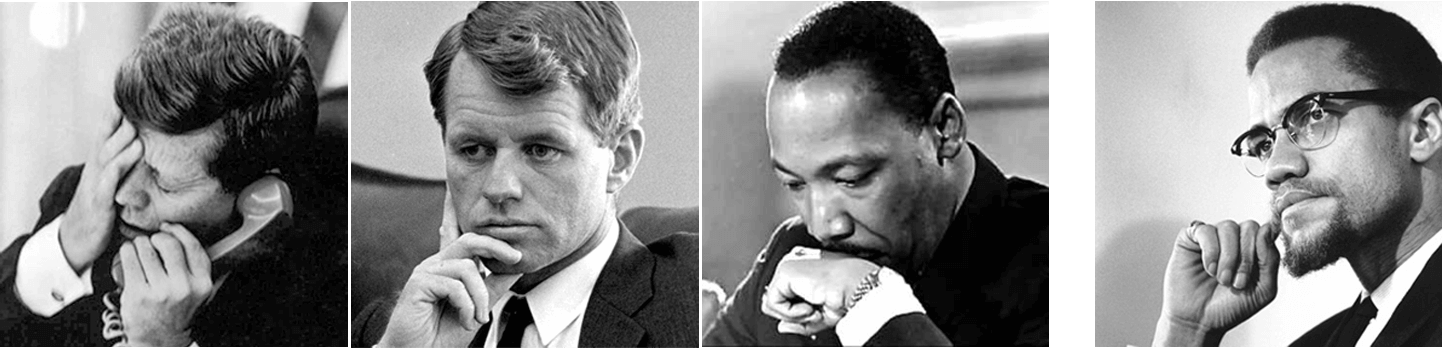

This is William O'Connell, and we're talking again today about The Warren Commission Report on the assassination of President Kennedy. And we have in the studio, Harold Weisberg, the author of Whitewash, and an even newer book called Whitewash II, which is subtitled, "The FBI-Secret Service Coverup". Mr. Weisberg is a newspaper and magazine writer, and a former Senate investigator, and also an intelligence and political analyst. His earlier specialties included cartels and economic and political warfare, and then during the early days of World War II I believe, your personal investigations and writings were credited with laying a foundation for the taking over of enemy property, and foreign funds controls. Is that correct?

Weisberg:

Yes, and the government got a pretty good income from some of the cases.

O’Connell:

One of the things that I especially wanted to go into in treating, as we are now some of the evidence in the case, in great detail and with thoroughness, I wonder if we could examine the reconstructions by the commission of the assassination itself from the Depository area on Elm Street, and also the reconstruction that the commission gave to the slaying of Officer Tippit. And to lead into that, I wanted to ask you about a statement that you make, and ask how you justify so categoric a statement, when you say that Oswald could have killed no one.

Weisberg:

I add one thing to it. According to the commission's best evidence. And I believe on this subject, the commission's best evidence is quite credible. The commission established Oswald's innocence because of the bankruptcy with which it approached the effort to establish his guilt. Everybody is familiar with the more dramatic aspects of this. For example, the witness Howard Brennan. Perhaps the least credible witness in any official proceeding. This is a man who qualified himself as a witness by saying that he lied when it served his convenience. He was taken to a lineup to identify Oswald, and he is presumably the source of the description, and yet at the lineup, he said he couldn't identify Oswald.

O’Connell:

When you say the description, you mean the description that went out over the police radio, with reference to a suspect in the President's slaying?

Weisberg:

Yes, now this addresses, this simple thing of the description that went out over the police radio, in a very comprehensible way, addresses itself to the integrity of everybody involved. We're led to believe that this description came from Brennan. Recognizing the improbability of it, the commission said, "Most probably." Now here we have a man, who is the source of the identification of an assassin. A presidential assassin. The police presumably are going to solve this crime. And they get a description from him and they broadcast the description. But strangely enough, the police don't know who gave them the description, so when the case comes to trial as presumably it was always intended to, they have no way of producing the eyewitness.

Either Brennan was the eyewitness who gave them the description that was broadcast, or he was not. Either the description that was broadcast came from an eyewitness or it did not. Now if it came from an eyewitness, how in the world were the police going to produce him if they didn't know his name? How are they going to have a witness for the trial? The description that is broadcast is not that of Brennan. It contains information that Brennan did not give, if any of this can be regarded as information.

O’Connell:

There was no information as to the nature of the clothes worn by the suspect in the broadcast that was give out as-

Weisberg:

Correct, but Brennan did give such data, and it contained information on a weapon, which Brennan did not give.

O’Connell:

Now where was Brennan standing in relation to the Depository building?

Weisberg:

When we get to Brennan, I will qualify everything by saying, "according to."

O’Connell:

All right.

Weisberg:

Because this is the least credible man in the world.

O’Connell:

All right then, instead of beginning with Brennan, let's go back and see if we can retrace in some kind of sequence the reconstruction, and then you take it back to, as earlier point then the 22nd if you like Mr. Weisberg, in terms of what the commission alleges in terms of the reconstruction as to the weapon, and the paper bag, and so on and so forth. But I think we should treat this in some detail, and preferably, chronologically if that's all right with you?

Weisberg:

Well, since we've already started with this thing of Brennan, let me finish with that first, because the reader of the report is led to believe that even though the commission almost disavows him, Brennan is the identifier of Oswald, and Congressmen Ford, in his own writing for profit, identifies Brennan as the most important witness before the commission. The truth of the matter is, that the important witness here was a Dallas Police officer, Marrion L. Baker, whose credibility was in the same class as Brennan's. I have in both my books, traced many of Baker's statements. The thing that distinguishes him from all other witnesses that I have studied, and I've studied most of them, is that on none of the many occasions he was interviewed did he ever give the story that he gave before the commission.

O’Connell:

Now, who are you speaking of now?

Weisberg:

Baker. Marrion L. Baker, the Dallas police officer, who had this famous gun in the gut encounter with Oswald in the second floor lunchroom of the Texas School Book Depository building. Now, it is Baker who tends to make credible Brennan's story that he saw Oswald in the sixth floor window. And it is Baker that did in fact, have an encounter with Oswald. There can be no question about this. There was ...

O’Connell:

Now where was Baker in the motorcade?

Weisberg:

Baker was in one of the follow-up motorcycles. He was not flanking the President. He was behind him. And according to his testimony, he had just turned from Main Street, down which the motorcade had gone through downtown Dallas.

O’Connell:

Was he immediately behind the presidential car?

Weisberg:

Several cars behind. He, I think that his testimony will place pretty much where he was. The motorcade turned from Main Street to the right, or to the north on Houston, and then turned to the left down Elm Street, which in a sense flanks Main. It was Baker's testimony that he had just turned from Main into Houston, when a gust of wind hit him - and there was a strong wind there that day, It almost blew Mrs. Kennedy's hat off at the same corner - and just after he turned the corner, he heard the first sound that he identified as a rifle shot. He testified that he revved up his motorcycle and got close to the Depository, jumped off and dashed into the building. In the building, he picked up Roy Truly, the manager, who was a credible witness, and they rushed upstairs, intending to go to the roof.

Because what attracted Baker's attention to the building, was not anybody in the window and he had at least as good a view as Brennan, and I tell you a better one because Brennan was close to the building, he was looking upward at too sharp an angle. When they got to the second floor, there-

O’Connell:

Too sharp an angle to ...

Weisberg:

To really see well. Because he was looking sharply upward. Baker was looking at a more flat angle, because he was looking, not from far away, but from a little bit of a distance.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

Brennan said that the man he saw was leaning up against a wall, and Baker as I say, was looking closer to straight on. Now it's six stories high, but the distance from between Elm and Houston is sufficient, so that the angle of Baker's vision included more than the angle of Brennan's vision. I make this point simply to point out, that with Baker having had his attention attracted by the first shot, and having looked at the building, he reports having seen nothing in that window.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

And his attention was attracted to immediately above the window to the roof. And he testified that the flight of pigeons from the roof made him suspect that something might be there. And it was for this reason, not because he saw anybody in the window, that he dashed into the building. And he picked up Mr. Truly, the manager, and they rushed to the second floor. Now to give you an idea of how they rushed, everybody who testifies about it in effect says that Baker was bowling people out of the way. They hit the two way door, the double hinged door on the first floor, that's so common in offices, just a waist high door, so hard and so fast that the mechanism wouldn't operate. And they rushed to the second floor.

Now the stairway in the school book depository building is an open stairway.

O’Connell:

This is the front stairway, I think it's-

Weisberg:

No, this is the back stairway.

O’Connell:

This is the back stairway.

Weisberg:

Listen, I'm talking now about where they were going up in the building. They got into the building, they went through the double hung door, and at Truly's lead, they went to the back of the building.

O’Connell:

This is in the ...

Weisberg:

First floor.

O’Connell:

The first floor and it's in the ...

Weisberg:

Rear.

O’Connell:

The western, the northwestern corner of the depository, is it?

Weisberg:

Yes, yes. Now they're elevators there, but both of the elevators were up in the upper floors, so Truly led Baker up the stairs and they were really running. Truly was ahead of Baker. When Truly was going from the second to the third floor, he became aware of the fact that Baker was not behind him. And he retraced his steps, and he found that Baker was inside a lunch room.

O’Connell:

Mr. Truly is the manager of the building, yes?

Weisberg:

Manager of the building.

O’Connell:

And he was standing where at the time of the assassination?

Weisberg:

Out in front of the building.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

And incidentally, he in common with most of the men who were employed by the building thought the shots had come to the right of where they were standing, and they were standing almost directly underneath the sixth floor window.

O’Connell:

And to the right would have been in the area of what-

Weisberg:

Of what has come to be known as the grassy knoll. A raised place along Elm Street. Now, when Truly retraced his steps to look for Baker, he found Baker inside a lunchroom. This lunchroom has access through two doors, one of which is set at a 45 degree angle, and has what amounts to a peep hole in it, not much larger than a book. Baker's subsequent testimony was, that he saw something through this window. Now had he seen something through the window, somebody would have had to have been there to attract his attention. Because the angle is entirely contrary to the testimony. The angle at which he could have seen something would have shown him a blank wall, unless Oswald had just walked in. But this is hardly probable, unless Oswald walked in and just stood still. Because the door had an automatic closure on it, and the door was entirely closed when first Truly and then Baker went past.

O’Connell:

Well now they were mounting the stairs, not to go into the lunchroom but to go to a higher floor.

Weisberg:

To the roof. Now meanwhile, these stairs, had Oswald been on the sixth floor, the only way he could have gotten to the second floor was down these stairs. Which means that he had to have gotten into the lunchroom before he would have been visible to Truly. And this is an open stairway, remember, and with wide passages around it that were used for storage, desks where there, and so forth. It was a large area. So Oswald have had to have been inside the lunchroom and the door had to have closed, before Truly reached the second floor. And I say before he reached the second floor because I've emphasized it's an open stairway.

Now as I say, I have at least a half dozen statements by Baker. In not one case did he say what he testified to. He placed Oswald, I'm sorry, he placed his encounter with Oswald up to the fourth floor. He placed it at various points along the second floor, in and out of a lunchroom, and in fact he said Oswald was holding a Coke in his hand.

O’Connell:

Well now, did he testify to this before the commission, or in his initial interrogations?

Weisberg:

What I'm talking about is all of the various interrogations which both preceded and even follow - a very strange thing - followed his testimony before the commission.

O’Connell:

He was interrogated after he appeared before the commission?

Weisberg:

He was actually interrogated the very day before the report was issued. I can make absolutely no sense out of this, it is the most rudimentary kind of interrogation and I reproduce it in Whitewash II. There's an FBI handwritten report, I'm sorry, a handwritten statement taken by an FBI agent in the presence of a witness. He took one from Truly that day, and one from Baker. And this is a well-spaced, single page in length. It's perhaps a hundred and fifty words. A very rudimentary thing.

O’Connell:

Well, how does it differ from what he told the commission?

Weisberg:

It differs what from what he told the commission in two respects. First, Baker says in this statement, that he was on the second or third floor, which is not at all the same thing as saying he was inside the lunchroom on the second floor. And it shows the indefiniteness of his recollection, even after he had testified. And further he said-

O’Connell:

He was more precise before the commission, in other words.

Weisberg:

Well yes indeed, he said exactly what the commission required. He said things that the commission required and he was led to say things that the commission required, that he could have no knowledge of.

O’Connell:

What in your opinion did the commission require then, as you put it?

Weisberg:

The commission required that Baker establish that he could have got into the encounter with Oswald, after Oswald reached the lunchroom. Now before we go into that, let me say that the second thing in this statement of September 23rd, 1964, the very day before 900 printed pages were given to the President, is that Oswald was standing there drinking a Coke. Now-

O’Connell:

Yes, that was popularly circulated in the press everywhere at the time.

Weisberg:

At the time, right. And then subsequently denied. And the commission goes to great length with a woman witness, Mrs. Reid, to have her recall after many months, out of all the things on that tragic day that Oswald was holding in his hand, and a fresh Coke that he hadn't started, because the commission didn't have these few seconds. The time required for Oswald to have gotten a coin, operate the slot machine that dispensed the Coke, and to open it to start drinking it was time, no matter how few in seconds, the commission just didn't have. That'll become clear as I tell this story.

O’Connell:

Well, excuse me for interrupting at this point. Didn't the Chief Justice himself pace off the distance from the so called sixth floor perch of the assassin, to the lunchroom, and didn't he clock himself or time himself?

Weisberg:

Yes. Right, right.

O’Connell:

And what did he determine as a result of that?

Weisberg:

That the commission's story was possible.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

The truth is, that the commission's story was false and I doubt if the Chief Justice was aware of the elements of falsity. Mr. Dulles at one point suspected it, because he asked of Mr. Baker, "Did the time reconstruction start with the last shot?" And Baker said, "No, the first shot." Dulles said, "The first shot?" And Baker said, "Yes, the first shot." And Dulles then said, "Oh." And it's a very eloquent "Oh" because it is quite obvious that the assassin's timing could not begin with the first shot but had to begin only after the last shot. In other words, he had these additional shots. The commission says two, to fire. Again, we're dealing here with seconds, and that's what makes this so important. So, not only did Baker begin at the wrong time, but it's clear--and again Mr. Dulles is quite helpful--perhaps without so intending, in establishing the fact that the timing of Baker began also at the wrong place by about a hundred feet. So in this way, the Baker end of the reconstruction was considerably helped.

O’Connell:

How do you mean, wrong by a hundred feet?

Weisberg:

Well you see the problem was to get Oswald to the scene of the crime, I mean to the scene of the encounter, before Baker got there. So they started Baker farther away to give him more time. And then they slowed him down, and they slowed him down in two different ways. There were two reconstructions involving Baker. One was a walking reconstruction, which is pure fraud. Because it's just no question about the fact that Baker was running as fast as he could. Not only did he so testify, and not only did everybody else testify that way, but how in the world would he have possibly been rushing up to the top of a building, to catch someone he thought might be killing a president... and walking? Not even for Dallas police is this an acceptable standard.

O’Connell:

Was there some testimony by spectators standing on the front of the steps of the building, to the effect that he was either running or walking? What was that testimony?

Weisberg:

Certainly. He bowled right through them. He scattered them in all directions. This is what I began by saying, that he bowled people over.

O’Connell:

Yes, I remember.

Weisberg:

So, you see, by beginning Baker at the more distant point, and at the more distant time, a hundred feet too far away, and two shots two far away, they increased the time it took him to get to the second floor. By having him walk, they again increased the time. But of course, the walk was pure fraud. So they engaged in an additional counterfeit, which have him in his words, go at a, "kind of a trot." Now, Baker also did not go at a kind of a trot. He just ran like the dickens. So this is the way they stretched out the time that it took Baker to get there.

And on the other hand, they had a reenactment of Oswald. And this was a very gentlemanly reenactment, because they didn't want Oswald to soil his hands, or to disturb the array of his clothing. The story is that Oswald hid the rifle, and the commission prints a number of pictures, all of which are indistinct and unclear, of the rifle where it was found on the-

O’Connell:

He hid the rifle.

Weisberg:

That's what the commission says. I tell you he did not. Now this rifle was not just tossed off someplace. Arlen Specter, the now district attorney of Philadelphia, says in some of his private interviews and Mr. Specter--like Mr. Liebeler in Los Angeles, and so many of the other commission counsel--are quite selective in who they will speak to and who they will debate. They usually pick either people who know less about this story than is possible to be known, or reporters who are knowingly sympathetic. They consciously avoid unreceptive audiences. Mr. Specter says that Oswald gave his rifle a healthy toss. Now that is just in defiance of all fact and reality. Because the rifle was hidden behind the barricade of boxes, school book boxes and cartons of school books, about five feet high. And it was not only hidden behind it, but it was standing in the same position in which it is held when it is operated. It was carefully placed. This is not all.

O’Connell:

Well they are photographs of the position of the rifle when it was found in The Warren Commission Report, I know that.

Weisberg:

Yes indeed, but these are incompetent photographs, because the commission found that it was better for some of his pictures to be less clear than they could have been. I went to the original source of the pictures, in the commission's files. And I reproduced the picture, one of the many pictures, and there's a whole incredible story here we can come back to about the kind of photography, the photographer getting himself in the picture and making fingerprints all over the place. But this rifle, in addition to that, was put under a bridge of boxes. There are two 60 pound cartons of boxes which overlap and form a bridge, and it was underneath these boxes, inside the barricade, that the rifle was hidden. Now he went to this detail, simply-

O’Connell:

The boxes weigh how much?

Weisberg:

Sixty pounds apiece on the average. This came out subsequently when the commission wanted to know how heavy the boxes were, because some boxes were moved. They were repairing the floor that day, and a considerable number of boxes had been moved and stacked in places they ordinarily were not kept. So Oswald had to scale the barricade, about five feet high. Very carefully place the rifle on the floor. Very carefully push it underneath the bridge formed by two boxes, one of which rested on the other with an open space underneath them. Then come out. In the course of doing this, I will anticipate myself a little bit. In the course of doing this, the subsequent investigation by the police established another qualification: and he had to leave no fingerprints.

Now Mr. Truly was asked, you will not find it in the report, but I have that report. I have the FBI report on this. Why the commission left this out, only the commission can answer. But the question came up about gloves. And all-

O’Connell:

The commission said he wore no gloves, did they not?

Weisberg:

It was more than just that. None of the employees there used any gloves. None of the employees on the sixth floor.

O’Connell:

When I say he, of course I meant Oswald.

Weisberg:

Yes. Now however, these boxes were checked for fingerprints by the Dallas police. Now here we have an entire barricade of boxes, four sides, five feet high. And the boxes inside, under which the rifle was hidden, and strangely enough, they bore not a single fingerprint. Not any kind of a fingerprint.

O’Connell:

Whereas the cartons at the window, or near the sixth floor window, did bear certain fingerprints. What fingerprints were found on those boxes?

Weisberg:

Oswald's, the fingerprint of the Dallas police investigative officer, Officer Studebaker. FBI people. I think there were more FBI prints than anything else.

O’Connell:

Well now you argue in your book, and it seems to quite reasonable, you maintain that there's no reason why Oswald's fingerprints should not have been on those cartons at that particular time. He was supposed to be moving cartons on the sixth floor of the Depository.

Weisberg:

He was paid to do it. It's very clear, that most of his work was on the sixth floor. Each of the employees specialized in the books of a particular publisher, and Oswald's function was largely with books published by Scott Foresman, and they were stored exactly where the boxes that had his fingerprints were. So there's nothing at all unusual about that. What is unusual is boxes without fingerprints. We've got an entire barricade made. Oswald supposed to have gone over it to put the gun behind it, and he had to come out because he wasn't there. And no fingerprints on this barricade of boxes.

So when the commission reenacted the time it would have required Oswald to go from the sixth floor to the second floor, they found it expedient for someone else, not Oswald, to dispose of the rifle. I mean this is so much of a charade, it's just so unbelievable that I involuntarily laugh. There's absolutely-

O’Connell:

Did you say they found someone else to dispose of the rifle?

Weisberg:

Oh yes, they just didn't time Oswald going over the barricade. He just handed the rifle as he walked past. Just handed it to another. The man who took Oswald's place was a John Joe Howlett, the Secret Service agent regularly stationed in the Dallas Office. So as he walked through- and he had to walk they couldn't have Oswald run because there were three employees underneath and they'd heard nothing.

O’Connell:

So you're speaking of the man who duplicated what the commission said Oswald was supposed to have done, and his name was Howlett?

Weisberg:

Correct, John Joe Howlett, the Secret Service agent of the Dallas Office. Now the sixth floor was so thoroughly stacked with books that it wasn't possible to take a diagonal from the southeast corner to the northwest corner. So in reenactment, Howlett winded his way a lot faster I'm sure than Oswald could have, had he been there, and I again say he was not there. And when he got to the stack of boxes, it was as though he said, "Please kind sir, will you take this?" And handed the rifle and then he walked on down the stairs. Now, this is one of the ways in which Oswald's time was shortened. Because the problem was to get Oswald to the encounter before Baker. If he didn't get there, not only before Baker, but before Truly could even have seen him as Oswald was coming down the stairs.

O’Connell:

And Truly was in advance of Baker, yes.

Weisberg:

And Truly's going up. Then the whole story's false, which of course it is.

So, Oswald couldn't be running, because underneath Oswald, allegedly, on the fifth floor were three employees of the Depository. And these were men with remarkably acute hearing. They could hear the shells drop as the gun was firing. That's not the only thing remarkable about these men. They were able to attract to themselves, variations in the law of nature. They were able to alter the law of nature so that the commission story could be helped. So, I'll give you an example of these remarkable powers, because all of this is a remarkable story.

There was Bonnie Ray Williams, who was looking out the window. His head was through the window. There are existing pictures, you may remember Dillard's pictures, the photographer in Dallas.

O’Connell:

Yes, the Dillard photographs, yes.

Weisberg:

They very clearly show that, at the time of the assassination, Williams head was through the window. Now this was not a wall like in a house. This was a foot and a half thick wall. And Williams had his head out of that. But, the testimony of these men is, that the explosion of the shots above them, which didn't deafen their ears, they could hear the shells fall, was of such great power that in this very durably built warehouse building, where thousands, and thousands, and thousands of pounds of books were in small areas of a floor, the explosion of this one small shell, because the bullet's only about a quarter of an inch in diameter was sufficient to jar dust and debris loose from the ceiling of the fifth floor, which is of course part of the floor of the sixth. And it fell down and it fell on Williams' head.

Now in order to do this, it had to have an L shaped fall. Mr. Newton was not consulted.

O’Connell:

Now who's Mr. Newton?

Weisberg:

Isaac Newton and the law of gravity.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

This debris must have fallen, not only straight down, but then it must have executed a 90 degree turn and gone out into the face of the incoming wind from the open window, and to have deposited itself upon Mr. Williams' head.

O’Connell:

Well now you're basing this on your study of the ... well it isn't a study. All you have to look at is the Dillard photograph and determine-

Weisberg:

And read the testimony.

O’Connell:

Yes. Well the Dillard photograph was taken during the assassination, is that correct?

Weisberg:

Within seconds.

O’Connell:

Mr. Dillard was approaching the Depository on Houston Street.

Weisberg:

He was in about the sixth car, and he was on Houston Street, and he looked up.

O’Connell:

So he got a clear view, straight ahead.

Weisberg:

Yes. And he snapped one picture instinctively, and he then, when the car got to the corner, he jumped out and changed lenses and snapped another picture.

O’Connell:

Well he snapped the Depository, he felt that there was a gun or a rifle.

Weisberg:

He thought that he had seen something stick out, I've forgotten now. Either he or another one of the newsmen in the car saw a projection from the sixth floor window, and he immediately snapped it. And this is the way newspaper photographers work.

So we have Oswald, in reenactment, leaving. He can't run, and he doesn't put the rifle away, and he goes down the stairs. With all of this, the time of Oswald and the time of Baker, with Baker at only a kind of trot, with all of these errors in favor of the situation the commission was trying to create, they still couldn't get Baker to the second floor lunchroom after Oswald. The difference was perhaps a second. I don't want to quote statistics and be wrong, but I think the difference was something like one minute and 14 seconds, and one minute and 15 seconds.

Now this one second difference, even if we accede to the 100 foot error in Baker's beginning point, and the two shot error in Baker's beginning point in addition to that, and if we forget all about this great magic attributed to Oswald, the scaling barricades and hiding rifles without taking any time and without leaving any fingerprints. With all of this, with only a one second interval, it just isn't possible, because remember there was Roy Truly in advance, and there was the open stairway. Roy Truly could have seen the lunchroom door when he was only halfway from the first floor to the second floor.

O’Connell:

Is there any testimony to suggest from people who worked in the Depository who were there in the building that particular day, that they heard anyone running down the stairs or descending the stairs?

Weisberg:

To the contrary. All the people who were questioned say exactly the opposite, that no one went down the stairs, no one went down the elevators. There was one employee on the fifth floor, Jack Dougherty, who was right at both the elevators and stairs because they're side by side, and he said at that time he was there and nobody went past. So the commission just ignores that.

O’Connell:

Now, Jack Dougherty was the ...

Weisberg:

He figures in another story that we'll come to.

O’Connell:

Was the person that saw Oswald enter the building.

Weisberg:

The only person who saw Oswald enter the building that morning was Jack Dougherty, and he swore that Oswald carried nothing. This is misrepresented regularly by the report and the commission counsel, who say that Dougherty thought he saw nothing, and thought he saw Oswald enter the building. Dougherty's testimony was explicit. He said, "Absolutely," and he was asked this word.

O’Connell:

Now with reference to the paper bag, I want to ask you a question. When Oswald arrived at the Depository that morning, he was in company of Wesley Frazier who drove him from Irving.

Weisberg:

May I suggest a rephrasing?

O’Connell:

Yes.

Weisberg:

When they arrived at the parking lot, they were together, but Oswald left in advance.

O’Connell:

But what happened after they arrived at the parking lot?

Weisberg:

Well, in order to tell you what happened when they arrived, I'm going have to depart from the report, because the report finds it expedient to make a slur, to make an entirely invalid inference. That inference is there was something sinister in that for the first time, on a number of occasions, on which Frazier had driven Oswald to the Depository building where they both worked. Oswald had a need to leave ahead of Frazier.

O’Connell:

Well you make very clear in your book, you quote the testimony to the effect, Frazier was driving an old car, and that he decided to remain in the car for a few minutes to ...

Weisberg:

Charge his battery.

O’Connell:

Charge his battery, yes.

Weisberg:

Now this is in the testimony, but it's not in the report. The report makes the sneaky inference I was just giving you. I think we should back up a little bit on Frazier, and take the story more chronologically if you don't mind, so the people will understand.

O’Connell:

Please.

Weisberg:

We're talking about this additional piece of magic, the homemade bag in which in defiance of 100% of the testimony, the commission avers that Oswald took a disassembled rifle into the building. I think we ought to begin this story the day before, and to say that Buell Wesley Frazier, a young man who was Oswald's co-worker, lived with his sister who lived a block away from the residence of Ruth Paine in Irving, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, where Marina lived all the time and where Oswald spent weekends. And he listed it as his residence, and as a matter of fact, the police acknowledged it as his residence. The rooming house that he had in Dallas was a temporary thing, or the room in the rooming house.

The night before the assassination, according to the testimony, and this is only Frazier's because remember, Oswald was denied testimony by the simple expedient of allowing him to be murdered. And this is no exaggeration, Oswald was murdered, only because the police made it possible. Oswald said he wanted to go to Irving, and Frazier said of course he'd take him, and this is the way Oswald normally went back and forth. Subsequently, when Frazier was interrogated by the commission, he made it explicit that Oswald had nothing with him and that on none of the occasions that he had taken Oswald to Irving from Dallas, had Oswald ever carried anything.

In defiance of this, which is 100% of his testimony, the commission alleges in the report, that Oswald took a bag that he had fashioned from the wrapping materials in the depository to Irving. Now this bag is clearly visible in the commission's photographs. A remarkable bag. We have remarkable bullets, remarkable reconstructions, everything is remarkable. What's remarkable about this bag? That it would hold creases. Hold them for months. But it wouldn't hold stains, it wouldn't hold fingerprints. It wouldn't hold the markings of a rifle.

O’Connell:

This was the testimony of Cadigan, was it the FBI ...

Weisberg:

In part, yes.

O’Connell:

Is he an FBI expert?

Weisberg:

Yes, he's an expert in this sort of technical information. Now the pictures of this bag show it was folded into squares that look to be about 10 inches square. And I suggest this will not fit into anybody's pocket. So that when Frazier said that Oswald was carrying nothing, I think his testimony is credible, because a 10 inch package, even if it's a small package, I mean if you ask a man, did so and so have a newspaper, he'll remember that small.

O’Connell:

Now you refer to a 10 inch package?

Weisberg:

It's approximately a 10 inch square into which the bag was folded. I say approximately because the report doesn't tell us. They find it expedient to make no reference to it.

O’Connell:

Well now you deal with the testimony and the attempt to test the recollection on the part of the commission, to test the recollection of the witnesses Frazier and Randle as to the size or rather the length of the bag.

Weisberg:

As Oswald was carrying it. So in defiance of its only testimony, the commission says Oswald took the bag to Irving, Texas. Now again, we have this strange strangeness.

O’Connell:

He took the bag to Irving, Texas you say.

Weisberg:

An empty bag that he had fashioned from wrapping materials at the Depository. No I do not say it, I say he did not, but the report says it. They had to get the bag there, in order to get the rifle into the bag, to get the bag and the rifle into the building so the President could get killed in their version.

O’Connell:

Could you tell how the bag was constructed?

Weisberg:

Well I can tell you how they say it was constructed. I do not vouch for it and I do not believe it. The bag is supposed to have been made from wrapping paper, taken from a roll of wrapping paper, that was then currently used in the Book Depository building, and to have been shaped by folding and to have been sealed by paper tape that is used to wrap packages to seal them. Now there was one man, and only one man who was in charge of the wrapping table. And he was unlike most of the other employees of the Texas School Book Depository. A man who was almost lashed to his work bench.

O’Connell:

This was Troy Eugene West?

Weisberg:

Troy Eugene West. The commission, which has so much trouble with the testimony on the bag, and which had to use testimony, which was diametrically opposed to its conclusion, decided that it had best forget all about the testimony of Troy Eugene West, and he is not mentioned in the report. But it was the testimony of West that he got to work early, filled a pot with water so he could make coffee, and thereafter never left his work bench, the wrapping table, for the rest of the day.

O’Connell:

What day was that?

Weisberg:

The day of his testimony, I don't recall, but he-

O’Connell:

No I mean, when did he ... he's referring to his arrival at the Depository.

Weisberg:

Every day.

O’Connell:

I see.

Weisberg:

This was his custom. He never left his work bench, he said. And he said that Oswald was never there, that Oswald never got any paper, that he never had access to any paper. He testified 100% against the interests of the commission's story that Oswald was the assassin.

O’Connell:

Now you point out in your study, Whitewash, that the tape that would be used in fashioning the bag, came from a dispenser in a wet condition.

Weisberg:

That's correct. Again, this is from the testimony of West. Because the tape from which this bag was made bore the cutting edge marks of the dispenser. When tape is dispensed, and it's torn off or cut off, there is a mark left, and it's identifiable. It's saw toothed usually. Sometimes it's not, and in this case, the tape on one end, which really means two ends bore the mark and the tape at the other end did not, like it was torn, you know by hand. But the mark of the cutter is there. So West was asked about this, because after all, the commission counsel wanted to show that Oswald could have done it. So West said, "There is no way of taking tape from this machine without it being wet, and without it bearing the mark of the cutting edge without disassembling the machine."

Now if the tape is dispensed through the machine, and I've used many of these as perhaps you have, they all have one thing in common. There is a reservoir of water and a brush like device which rests in the water, and by capillary action, water is fed up to where the tape is. And the tape slides across, brushes across the top of this brush, and thereby becomes wet. So that when it comes out of the machine and is dispensed, it's in condition to use. And this invariably is so, unless as West said, you disassemble the machine, and when you disassemble the machine, you don't have the marks of the cutting edge. So here again, West is totally destructive to the commission's evidence.

Now we'll get back to Oswald, about to commit this crime, and despite all this evidence, which is 100% opposite to its conclusions, the commission, by its own special kind of evidence, has him in Irving, Texas. Where nobody sees him with a bag, nobody sees him with a rifle. Nobody sees him take a rifle apart. Nobody sees him put a rifle, taken apart or not taken apart into this bag, and nobody sees him leave the Paine residence with it. Instead, what actually happened is that Oswald went to bed early that night, and he was so completely untroubled by this awful deed he was preparing, that he slept through the alarm clock the next day. He not only slept long, but he slept well. And about 20 minutes after the alarm clock went off, Marina woke up, and this is her story. Because after all, we still have no Oswald story, because the police never kept any record according to their story, of the interrogations.

So, Marina tells us that she awakened Oswald about 10 minutes after seven and his ride usually left at 20 after, sometime 25. And she offered to make breakfast for Oswald, and he said no, that he'd take care of it himself, and he said you stay behind and take care of the babies. So, Oswald ran downstairs and didn't make any breakfast, and went down to the Randle residence in the next block.

O’Connell:

Do we have any testimony as to whether he made a lunch? Wasn't he often supposed to have taken lunch with him?

Weisberg:

This time he did not.

O’Connell:

He did not?

Weisberg:

This time he did not. And there's an additional importance to this.

O’Connell:

Where do we learn that?

Weisberg:

I believe it is in both the testimony of Frazier, I don't recall now. But there was no evidence that I can remember... I might be wrong on this but I don't remember Oswald having taken a lunch that day. He had only one package, and it was a rather large package. It was about 24 inches long. There was some testimony that indicates it might be as much as 27. But because the commission's interest was in stretching the length of the bag, I'm inclined to believe 24. So, Oswald having overslept and having been awakened by his wife, who was subsequently quoted by the commission as saying he never ate breakfast, this time she said she'd make it for him. Then she said she was distressed when she found out he hadn't even made himself a cup of coffee. And he walked down the street to the home of Linnie May Randle, the married sister of Wesley Buell Frazier. These are both young people.

According to Mrs. Randle, she was in the kitchen and they were breakfasting when she saw Oswald coming down the street, and he was carrying a package. Her testimony is specific, it's graphic. It's the kind of testimony lawyers seek, because it has in it, exactly those kind of incidents by which people in real life do remember things. She said, "This looked like a grocery bag." That Oswald was carrying it, having curled and crunched up the top. He was carrying it by that at his side, swinging it at his side. And that the bag just barely cleared the grass. Now this pretty much fixes the maximum length on the bag at about two feet. She said that Oswald, when he got to her home and then opened the back door of her brother's car, put the package on the seat, and then himself got into the front seat.

It is Frazier's testimony that when he got out of the home and entered the car and said good morning to Oswald, he saw the package on the back seat, and has a clear recollection of where it was. And he subsequently, with great consistency, showed exactly how far from one side the package extended. And it was on the seat mind you, not on the floor. The commission doesn't go into this but I'd like to suggest it has some importance. If there's a disassembled rifle in flimsy bag with sharp, metal projections, and even the wood projections are sharp, loose screws, one sudden stop of that, and a telescopic sight. A fragile thing like a telescopic sight attached. A sudden stop of the car would have sent the package crashing from the seat onto the floor, and if it didn't break the package and reveal its contents, it certainly would have not benefited the functioning of the telescopic sight. And this is one that needed all the benefit it could have.

O’Connell:

Now the commission put to the test, of both Randle, and Mrs. Randle, and Frazier, with reference to the length of the bag, and in each case, their recollection was, they made them fold the bag, in before the interrogating body, did they not?

Weisberg:

Yes indeed, and let me describe this testimony for the benefit of the listeners before I explain it. The more the commission tried to destroy these two witnesses, the more they reinforced the story of both witnesses. And I'm telling you that the most serious kind of efforts were made to destroy the witnesses. For example, Frazier was arrested and taken to the police station and sweated. He was given a lie detector test and if you believe these things, the lie detector test proved he was telling the truth. The more the witnesses were wheedled and cajoled, and efforts made in effect to intimidate them, the more they reaffirmed their story and recalled specific things which made their stories even more credible.

Let me give you an example of this. The commission counsel kept asking Mrs. Randle to place a length of the package, and there are a number of incidents during which the counsel never says how long her representation is. There comes a point at which he seems satisfied.

O’Connell:

Who, the ...?

Weisberg:

The commission counsel, and he says, I've forgotten, was this Ball?

O’Connell:

I believe it was Joseph Ball, I'm not certain.

Weisberg:

And he says, "Well, we'll measure that," and they measure that, and it's 28 inches. And Mrs. Randle volunteered, "Twenty seven last time." And he said, "What'd you say?" And she said, "Twenty seven last time. I've done this many times and it usually comes to 27 inches." So all of her reenactments-

O’Connell:

Oh she had reenacted this before for-

Weisberg:

Oh, you know that all the police went over it with her time and time again, if the commission counsel didn't. With her brother, we begin with this misrepresentation by the report, that there was something sinister on this one particular unique occasion by Oswald, leaving in advance. Not at all was this the case, because Frazier testified that after he'd revved up his motor a little bit and left what he thought was a sufficient starting charge in the battery, he walked behind Oswald toward the Book Depository. My recollection is that they were about two blocks away. And he said, if he hadn't known Oswald was carrying a package, he might not have noticed it. Because Oswald had it cupped in the palm of his right hand, and tucked under his armpit.

O’Connell:

Well, isn't that consistent then to say that Jack Dougherty, who was the person that saw Oswald enter the building ...

Weisberg:

Would have seen something?

O’Connell:

Well, no, that he would not have seen something. That conceivably Oswald was, that this is consistent.

Weisberg:

Except for one thing, that Frazier was looking from the back, and Dougherty from the front. Frazier was behind Oswald, and Dougherty was in front of Oswald. Dougherty was in the doorway as Oswald entered, and they were face to face. Now, this could have been true if perhaps Oswald had been carrying something as small as a yardstick, but not for a package of a rifle. And the width of the package-

O’Connell:

Well then the question immediately arises, what happened to the bag that Oswald brought to the building?

Weisberg:

Well in the absence of any search by the government, or at least a reflection of any search, we have no way of knowing. You know they finally asked Roy Truly about it. I think we should tell the listeners what Frazier said Oswald said was in the package: curtain rods. And when the commission made an effort through its counsel to point out that they didn't think it was curtain rods, Frazier took issue with them. He said he worked in a department store and he'd handled packages of curtain rods, and this seemed to him like precisely that, a package of curtain rods.

O’Connell:

Well are you saying then that the curtain rods were sequestered somewhere before Oswald entered the building?

Weisberg:

I really don't know. Because again, I won't endorse any of the commission's testimony of this sort. It's the most dubious sort of thing. But what I will tell you is this, that with this story of Oswald having carried curtain rods toward, if not into the building, and with the inability of public authority to get those curtain rods inside the building, there is absolutely no search. Now there's all sorts of storage areas around there. One attached to the building. Sheds. It wasn't until the following August that an investigation was made, and this is the flimsiest kind of an investigation. A letter was written to Mr. Roy Truly, the manager of the building. Were any curtain rods found? Now you might think that the police, and the FBI, and the Secret Service, and the various detectives would have been interested in this. No interest. I suggest that the reason is obvious.

But in any event, months later, Roy Truly was asked and he replied, "All curtain rods found are brought to me." In effect, as though there was a special department of the Book Depository looking for mislocated curtain rods. Now there's nothing honorable about this. The obvious thing was to check that story out in complete detail. The obvious thing because public authority bears a responsibility. Most people don't know it Mr. O'Connell, but let me tell you, that the responsibility of a prosecutor under the canons of the bar association are not to convict people, but to establish justice. His function is dual. He is the prosecutor, but his obligation is justice. And there is absolutely no evidence that I have found that anybody ever thought to check out whether or not, Oswald had a package other than the rifle. Whether or not there were curtain rods, and as we know, all sorts of other Oswaldianna, if we can call it that, was not found until months later, weeks later, and then under the most mysterious and dubious circumstances, so there was no search for the package Oswald carried.

So we have this testimony that Mrs. Randle saw Oswald going to the car with a package. That Frazier saw the package in the car, and saw Oswald leaving toward the building with it. And that he followed them. Now again, the most serious and strenuous kinds of efforts were made to get Frazier to testify to what he would not testify to. He was a very stalwart young man to stand up to all this pressure beginning with arrest. And according to Frazier's testimony, there was real misrepresentation of what happened. Because he corrected the counsel on several occasions. For example, the difference between measuring a round package with a tape measure and a yardstick. Now this was an eight inch wide package, and even with a bulky overcoat, and Oswald's arm, and he didn't have one on by the way, he had a close fitting jacket. There's no possibility of an eight inch package.

O’Connell:

Yes, well the commission nonetheless feels incumbent to, feels that it is incumbent upon them to draw the conclusion, or I should say the inference that if Oswald, and it has been clearly established that he did have a bag with him, and that he was entering the Depository with a bag, or approaching the Depository with a bag, that indeed he did carry one in with him, because they maintain that such a bag was found.

Weisberg:

You will not find in the report that, at the entrance to the Depository building, there is an entrance to a shed. You will find it in pictures. When you have the official surveyors charts and three different versions are in the same thing in the one burden of evidence. Instead of the dimension of the building, instead of its outline, you have a child's representation of a line, like children are playing games. Every effort is made to not make available to the people, the knowledge that there was a shed at that point, but I tell you there was. And I'm sure your own recollection, from your own investigation is that there is one, right alongside the building. The FBI reports of various sort, talk about the end of the building proper, and the most obvious thing was to have checked there. I am quite confident that the police did check there, and I'm quite confident that they found nothing or avoided what they found.

But there is no doubt about it. The only one man in the entire world who saw Oswald enter the building according to the record, swore specifically and vehemently that Oswald had nothing. Now with this very questionable evidence, I think we can forgive the commission for making no effort to trace Oswald from the back of the first floor to the front of the sixth floor, with or without a package. Even though the building was at that point, loaded with all of the employees just reporting to work, or just beginning to work, and uniquely, something out of the ordinary for that building, the focus of work was on the sixth floor where a new floor was being laid. And all of these people working there, not one was asked, "Did you see Oswald at eight o'clock when he reported to work? Did you see him carrying a package?"

Now in another context, Mr. O'Connell, I have checked through the duplicated interrogations of about 63 employees of the School Book Depository on what they saw that day, and not one was asked this question. The Secret Service did it. I have found no evidence that the Secret Service asked the question. The FBI subsequently did it, and this was done repeatedly, and not one was asked that question. And I think that because the commission had to go 100% against all of its testimony, we may forgive them for not jeopardizing their case even farther. The commission's solution was very simple. They just said 100% of their evidence was wrong. Their own preconception was right, and thus did the rifle get to the sixth floor. Thus was it there for an entire half a day, with all of these people working there and nobody saw it.

O’Connell:

Well, now because of the requirements of time, I wonder if we could necessarily make somewhat of a jump, and I wanted you to address yourself to the when the commission maintains a bag was found on the sixth floor, when did that turn up?

Weisberg:

There's a little bit of indefiniteness about this, and here again, I think we perhaps had best be charitable and forgive them. Because the police identification squad immediately went to work and they have their own unique way of working. The first thing they did when they got into the building was to move everything. They got up to the sixth floor. And Studebaker's testimony on this is explicit, they scattered things right and left. There was a stack of boxes, remember, that the report says was used as a gun rest.

O’Connell:

You reproduce those in your book?

Weisberg:

Indeed, I do. Those is right. I only reproduce some of those, because I wanted to use facing pages so the reader could see everything with one view, and I have only four of these pictures. But having initially followed this unique Dallas science and police work, moved everything. And then according to Mr. Studebaker and others, put them back precisely where they were. Precisely? Each one is disproved by all of the others, and all four are wrong, and all of the others that I didn't include in Whitewash are also wrong, because the commission does reproduce them. Now it depends on which time you listen to which witness, how many pictures were taken. But it is officially certified that there were anything from 35 to 50 pictures and you can take your choice. In any event, taking the lowest number, 35, we have a rather generous supply of photographs of the area. Not one includes a bag.

O’Connell:

Well there's a-

Weisberg:

It's not because they didn't know the bag was there, because it is the testimony of Studebaker that he found it.

O’Connell:

There is one of the photographs contains dots where the commission says the bag was found, even though-

Weisberg:

We're back-

O’Connell:

I beg your pardon.

Weisberg:

We're back in the child's world again. Yes there were dots drawn into a photograph of that corner showing where the bag was found. It was found by the photographer who took pictures of everything else but not that. It was endorsed by a photographer, Lieutenant Day, who was the boss and the Chief of the Identification Squad, the boss of Studebaker, who went farther. He said he recognized its importance immediately, and he endorsed it with a time and place and so forth in his name. But this again, is a magical bag, a truly magical bag, because it didn't have the fingerprints of Day, and it didn't have the fingerprints of Studebaker.

O’Connell:

It did have some fingerprints of Oswald in it.

Weisberg:

I believe it was a thumbprint, and on the inside.

O’Connell:

On the inside of the bag?

Weisberg:

On the inside as the bag was fabricated. You know I think fabricated is just exactly the right word. Now, I have recently in my work, in the commission's files, which hither to are secret, found that the FBI refers to this too, but not as a bag. As wrapping paper. For the first several days, the FBI account is not that of a bag, but as a wrapping paper. So we have all of this magic with one incident. Magical boxes that don't hold fingerprints, magical boxes that do hold fingerprints, but the wrong ones, and unidentified ones. We have this magic of Oswald and scaling and leaving no record behind. We have the magic of the bag that isn't there, but is there. Of the pictures that are taken, but do not show it.

O’Connell:

What was the testimony of expert Cadigan with reference to whether the bag could have contained a rifle?

Weisberg:

It bore no markings of any rifle. It did not have any oil or any stain, and yet the commission says Marina testified that Oswald kept his rifle well oiled.

O’Connell:

Well didn't J. Edgar Hoover maintain that also, that the rifle was well oiled?

Weisberg:

Oh yes, oh yes, it was.

O’Connell:

Well what was the later FBI evaluation of whether the rifle was well oiled or not?

Weisberg:

I don't recall them ever saying it wasn't, but they did say at one point there was a little bit of rust. But it's my recollection that even that point of rust was covered by, "Oh, this was something in the bolt assembly." Now, the rifle, the middle of the rifle had more than the normal amount of access to the wrapping, because remember, the rifle, according the commission, and on this they didn't even dare take testimony because it couldn't possibly have been any such testimony. The rifle was about 35, 36 inches long disassembled. The maximum length it could have been to have met the description of the witnesses was 24 inches, so we give them a few more inches and make it 27 to 28. And when the rifle was put into a bag, a duplicate bag and Frazier was a witness and reluctantly he was forced to show how Oswald would have carried it, the rifle came up almost to the top of Frazier's head. And he said, "You see, I told you," when the counsel said, "Why that's above your ear." He said, "You see, I told you."

So again, not only did it not have any stains, but while months later it still preserved the creases into which presumably had been folded for transportation empty. It didn't contain the markings of the rifle, in which he had been dragging it all around Irving and Dallas, according to the commission's old story. But again, the bag is a magical one, like they have magical bullets and they have magical witnesses. And it's really black magic.

O’Connell:

I wonder in the very few minutes remaining to us, Mr. Weisberg, if you could tell us something about the cartridge casings that were found on the sixth floor. What markings did they have on them?

Weisberg:

They were magical, they were magical. They had no fingerprints. They were magical. They had multiple markings. The commission was profoundly uninterested. Imagine, Mr. Hoover said that, "These cartridge cases had been in this weapon previously, and in weapons that were not this weapon." In other words, these cartridge cases all bore additional markings. They were not just in this weapon one time.

O’Connell:

You're saying that they had been loaded into another weapon or weapons?

Weisberg:

And unloaded, and this one and unloaded. Now we have no way of knowing when they were fired. It's quite conceivable from the scientific evidence that the cartridge cases were fired on another occasion, put back into the rifle, and then just put in and ejected without anything being fired from them. But there's one, that absolutely was marked by a weapon, not this one. Now this type of marking is as unique as fingerprints. And the FBI's competence in this field is I think, without question.

O’Connell:

Expert.

Weisberg:

Oh absolutely, the best.

O’Connell:

From who did we get that testimony?

Weisberg:

That's Mr. Hoover's. He gave this in a report to the commission. And I don't think there's any question about Mr. Hoover knowing the FBI business, he invented it.

O’Connell:

Thank you. We've been talking this morning with Harold Weisberg, the author of Whitewash. Mr. Weisberg, as I mentioned, is an author from Hyattstown, Maryland. A newspaper and magazine writer, and a former Senate investigator. I want to thank you for coming to the studio today, Mr. Weisberg, and I hope that you'll come back and that we might address ourselves to Whitewash II, your second book, at a later date. Thank you so much.

Weisberg:

I'm looking forward to it, thank you.

This transcript was edited for grammar and flow.