Literally thousands of books on the topic of the John Kennedy assassination have been published, from tomes by major publishing houses down to limited-edition self-published work. Brush With History: A Day in the Life of Deputy E.R. Walthers is an example of the latter, made available in 1998. The author, Eric Tagg - a musician by trade, based in a Dallas suburb, and well-read in JFK assassination literature - consulted primary records and engaged his own research in the Dallas area to compose the book, by which its ostensible subject - Dallas Deputy Sheriff Eddy Raymond “Buddy” Walthers - serves as a pivot for detailed accounts of several otherwise unrelated sub-topics.

Walthers remains of interest due to his proximity to events on November 22, 1963. Over the course of about three hours, Walthers witnessed the President’s motorcade pass by; heard the shots; searched for evidence and identified witnesses in Dealey Plaza; witnessed Oswald’s arrest at the Texas Theater; and was among the first officers to arrive at (and search) the Paine home in Irving. This activity resulted in Walthers placing into the record a series of observations which would prove uncomfortable for the later emerging official story.

Consisting of five concise chapters (along with appendixes, notes, and index), spread across a relatively brief 217 pages, Brush With History makes its mark by attention to the details of specific, if tangentially related, events, rather than attempting another broad or over-generalized survey. In this manner it could be described as a book authored by a “buff”, written for fellow “buffs”. [1]

Walthers himself was killed during the botched arrest of a fugitive at a Dallas-area motel in 1969, the focus of the book’s fifth chapter. Attention to this somewhat sordid event is necessary as it occurred only a month before Walthers was scheduled to testify in New Orleans at Jim Garrison’s trial of Clay Shaw. This coincidence was responsible, in part, for the inclusion of Walthers in versions of the “mysterious deaths” list, referring to the possibly untimely, possibly sinister, demises of various witnesses tied, directly or not, to the JFK assassination. Author Tagg is convinced there was no such connection to Walthers’ sudden unexpected misfortune, and includes the transcript of an interview with Walthers’ policing partner Al Maddox, who was present in the motel room, to make that case.

The Maddox interview also sheds light on the culture of the Dallas Police Department in the 1960s, a topic addressed in the second chapter of Brush With History , which focusses on Deputy Roger Craig. Tagg, to his credit, does not shy away from acknowledging the Dallas PD of the time was riven with internal resentments and personality conflicts, which includes Craig’s assessment that Walthers was, in his opinion, a “chronic liar” who was never where he claimed to be on the afternoon of November 22, 1963. [2] Other department members are, conversely, quoted expressing poor personal opinions of Craig. Tagg chooses to emphasize the material record, and the pivot point which links Walthers and Craig, for discussion purposes, are photographs from Dealey Plaza, minutes after the shooting, which depict Walthers in the foreground examining possible bullet marks in the grass while Craig, in the background, can be seen making his controversial sighting of a station wagon, with a luggage rack, which may have picked up Oswald as a passenger. When this sighting was brought up to him, after his being placed in custody, Oswald was said to have responded “That station wagon belongs to Mrs Paine…” Later in the afternoon, Walthers could confirm seeing a station wagon, with a luggage rack, at the Paine household.

About twenty minutes or so after the shooting, as the Texas School Book Depository building was increasingly becoming a focus of police attention, Walthers had the presence of mind to start “gathering up witnesses, herding them into the Sheriff’s Office where they could be deposed before their stories were contaminated by others or news reports.” [5] While in the office, at about 1:15 PM, word arrived that a Dallas police officer had been shot in Oak Cliff. Being available for the call, Walthers, along with two civil deputies, drove to the neighborhood, during which he heard over the radio the President had died. Seeing that others were already on the scene of the downed officer, Walthers instead followed a dispatch call directing officers to the Texas Theater, where a suspect was believed to have fled. At the theater, Walthers witnessed the arrest of Oswald, and assisted in clearing a path to the squad car waiting to transport the suspect to police headquarters.

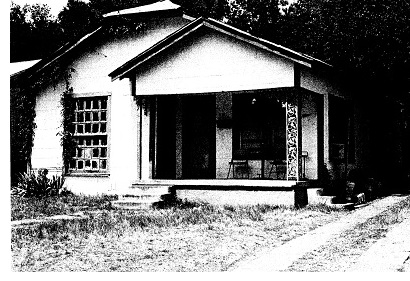

Back at the office, around 2:15, Walthers was assigned by Sheriff Decker to the Dallas suburb of Irving, to check an address associated with a “missing” Texas School Book Depository employee named Oswald, who was already in custody. Arriving at 2515 West Fifth St at about 3 PM, Walthers, along with a handful of other officers called to the scene, was greeted at the front door by Ruth Paine with the words: “Come on in - we’ve been expecting you.” [6] While officer Gus Rose spoke with Paine, the others had a look around. Walthers staked out the garage. There, as he would later attest, he noted a pasteboard barrel filled with Fair Play for Cuba leaflets, and six or seven “metal filing cabinets full of letters, maps, records, and index cards with names of pro-Castro sympathizers.” [7] Eventually, all relevant items were placed in the trunk of Walthers’ car and taken to the Sheriff’s office. [8]

Tagg sums up this rather full and consequential afternoon’s work:

“I hope that this study of the assassination case will make more people aware of (Walthers) role in virtually every aspect of the crime investigation and his uncanny ability to be at the right place at the right time that fateful day, discovering the key pieces of evidence both at Dealey Plaza and the Ruth Paine house. His off- the-cuff determinations of the sources of the shots, trajectories, and gathering of evidential artifacts ranks as the best police work done that day. His instincts took him immediately to the picket fence, the manhole cover on Elm, the curb on Main, the Texas School Book Depository and Dal-Tex Building, the Texas Theater, the Paine garage, and the Cuban headquarters on Harlandale…No one man was associated with more elements of first-hand primary involvement in the Kennedy assassination.“ [9]

Again, this ability to enthusiastically veer off into seemingly tangential yet fully contextual directions is one of the distinct charms of this book - a sort of Six Degrees of Buddy Walthers exercise - which will appeal to readers who appreciate the coincidental or associative minutiae of the Kennedy assassination’s expansive web.

Another fascinating detour is motivated by mention of the Abundant Life Temple, also located in Oak Cliff, a possible hideout for the Tippit gunman and therefore a focus of police attention before the diversion to the Texas Theater. This temple was part of a network under the umbrella of the American Council of Christian Churches, whose disparate organizations strangely featured membership of persons of interest in the Kennedy assassination such as Fred Crisman, David Ferrie, and Albert Osborne.

Tagg includes, in the appendix, a memorandum written by Jim Garrison in 1977 for the HSCA on the subject of Thomas E Beckham. [10] Garrison recounts some of the extremely interesting information uncovered by his investigators back in the late 1960s:

“We are, in short, dealing with bits and pieces of a clandestine structure and the harlequin roles of most of the key players are quite literally designed to make the traditional law-enforcement approach both time consuming and irrelevant.”[11]

In the case of Crisman, Garrison acerbically notes that he was an otherwise “intelligent, cool and forceful” Air Force pilot and Boeing employee “who, for no perceivable reason, at a critical stage in the Cold War, mutated into a roving bishop in a non-existent church…” [12] Cutting to the chase, Garrison concludes:

“I suggest that the most likely rational conclusion is that here, again -- except with more particularity — we have a clandestine substructure developed to serve the intelligence community's concept of national security. A bizarre structure, to be sure, but its very strangeness -- its threadbare irrelevance -- makes it all the more safe from possible investigators who are looking for spies wearing trenchcoats and carrying, like so many James Bonds, gold cigarette cases. The churches -- like all churches -- are virtually free from official inquiry by virtue of the Constitution, not to mention American custom. The ‘ministers’ and ‘bishops’ can accumulate money (religious fund-raising) without serious inquiry as to the source.” [13] (emphasis added)

Such bizarre coincidences such as the confluence of “roving bishops” with national security backgrounds into the fabric of the JFK assassination’s layers and layers of cover and deception is part of what gives this unsolved crime its continuing juice six decades on. Against that, it can be noted the application of traditional police investigative work, as conducted by Walthers on the afternoon of November 22, 1963, remains highly effective in establishing important factual information which could not be dismissed. For this reason, Brush With History remains useful and is worth seeking out.

End Notes

[1] Although the term has been utilized as a derogatory aspersion by various Lone Nutters over the years, “buff” is in fact an informal noun referring to “a person who is enthusiastically interested in and very knowledgeable about a particular subject.”

[2] Eric R. Tagg, Brush With History, Shot In The Light Publishing, 1998 p41, p43

Craig denied Walthers was ever inside the TSBD or the Texas Theater on November 22, 1963. Craig also described Walthers as “a small man with a very arrogant manner” in his manuscript “When They Kill A President”.

[3] Testimony of Eddy Raymond Walthers, Warren Commission Hearings Vol. VII. P546

[4] A photograph captioned “View From Main Street Curb Where Tague Stood” is included with this chapter, and demonstrates definitively how inconceivable it really is that a gunman situated in the TSBD’s sixth floor “sniper’s nest” could be responsible for the Tague shot. Warren Commission member Richard Russell’s dissent - that he didn’t believe a situation where a gunman could “miss the street” - receives visual confirmation with this photo. Tagg remarks: “It remains a mystery how the sniper in the sixth floor window could have missed so badly as to strike the curb way down Main Street. Only a shot from another location begins to make sense…” Tagg, Brush With History, p14

[5] ibid p15

[6] p 25

[7] ibid p27 This was later a controversial observation as the “index cards with names of pro-Castro sympathizers” was never listed in the record, and may have belonged to Michael Paine. In his Warren Commission testimony, Walthers followed Wesley Liebeler’s leading questions to claim not to know what was inside the filing cabinets, but his November 22, 1963 investigation report specifies: “Also found was a set of metal filing cabinets containing records that appeared to be names and activities of Cuban sympathizers.” )

[8] This as well was controversial, as the official story would claim that the evidence at the Paine household was not secured by police officers until the following day, when proper warrants had been arranged. But it is not in dispute that these items ended up with the FBI on the Friday night, and were the following day returned to the Dallas police in time for them to be officially and legally “found”. Tagg states that Walthers also discovered backyard photos on Friday, but this item is neither specified in Walthers’ Warren Commission testimony or his November 22 report. However, if the backyard photos were indeed discovered inside “a box of pictures” found in the garage and brought in to headquarters by Walthers, as he says to the Commission, along with the other Oswald possessions, it could explain how at least one backyard photo was seen by several persons, including Michael Paine, at the police station on the Friday night.

[9] Tagg, Brush With History p141

[10] Beckham’s reputed presence in Dealey Plaza in the shooting aftermath is discussed by Tagg in Chapter One of Brush With History.

[11] July 18, 1977 Memorandum to Jonathan Blackmer, HSCA, from Jim Garrison, re: Thomas E. Beckham see Tagg, Brush With History, p 143

[12] ibid, p 152

[13] ibid, p 154