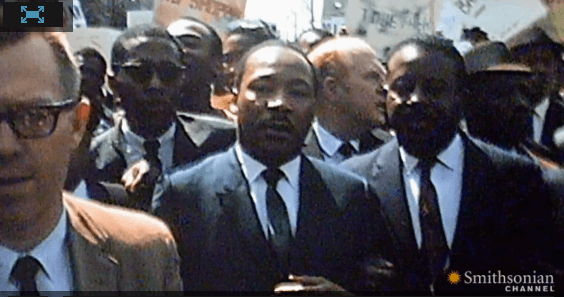

In 1979 the House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) released its report stating that there was a “likelihood of conspiracy” in the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Predictably, and in spite of the evidence, the HSCA found that James Earl Ray was the assassin and suggested that he was responding to an alleged “bounty” offered by a few right-wing southern extremists. For all intents and purposes, Stuart Wexler’s and Larry Hancock’s "The Awful Grace of God" is an updated and even more speculative version of this scenario. That there does not appear to be a shred of credible evidence to support any of it will hopefully be made apparent in the course of this review. The authors distinguish their work from that of the HSCA by not committing themselves 100% to Ray as the shooter. But this feels like little more than a token gesture intended to appease those of us who have actually studied the crime scene evidence. If the authors ever seriously considered anyone else in that role, or what other role Ray might have played, then I missed it.

From the moment Hancock and Wexler introduce the reader to Ray, it is crystal where they are headed. When asked by "The Daily Beast" whether or not Ray fired the fatal shot, Wexler replied, “He probably did, but the physical evidence is a morass we didn't really want to get into.” To most serious observers, this is a rather unusual viewpoint in the investigation of a murder case. The crime scene evidence is the most important evidence there is and should be the first port of call for anyone writing a book on this subject. This is especially so given that it all but proves Ray's innocence.

As I see it, one of the biggest flaws of "The Awful Grace of God" is its reliance on dubious, discredited, and biased sources. So before we get into the review proper, I believe it would be instructive to begin by briefly exploring a few of those sources the authors most frequently cite and most heavily rely upon.

William Bradford Huie

In 1960, author William Bradford Huie attempted to sue NBC over its program, "The American". He claimed it was based on his story, "The Hero of Iwo-Jima". Since Huie had claimed in his book that the story was true, the motion was denied, since historical facts not being subject to copyright laws. But Huie demonstrated for the court that elements he had claimed in his book as true were, in fact, “the product of my imagination.” (Mark Lane & Dick Gregory, "Murder In Memphis", pgs. 282-283) Despite his self-proven status as a self-admitted fabricator, Huie is one of the most frequently cited sources in "The Awful Grace of God". The authors write that Huie was “the first reporter to deal directly with Ray” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 151). But this is misleading. Simply because the two men never even met. The pair communicated through Ray's first attorney, Arthur Hanes. Sometimes Hanes would pass Huie notes written by Ray; other times he would simply forward verbal messages (in court this is known as hearsay). But Ray quickly became upset with Huie. Because he thought that he revealed too much of Ray's defense in an article for "Look" magazine, and suspected that he was passing information on to the FBI. From then on Ray began passing on obvious lies to Huie and their “relationship” deteriorated. Huie, who had begun writing about a conspiracy to kill King, now turned 180 degrees and proclaimed that Ray did it all by himself. And, as he had done with "The Hero of Iwo-Jima", Huie began adding details from his own imagination.

For example in his book about the King case, "He Slew the Dreamer", Huie claimed that a Canadian woman Ray had spent time with in the summer of 1967 had told him of an occasion when Ray had expressed his true feelings for blacks. According to Huie, Ray had remarked over dinner that “You got to live near niggers to know 'em” and that all people who “know niggers” hate them. But, as the HSCA found out, when the woman was interviewed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police she swore that Ray had never indicated any hatred of blacks at all. (HSCA Report, p. 328) Huie had simply invented the damaging quotations.

Perhaps the most telling incident concerning Huie's credibility occurred at the time the ill-fated congressional investigation was getting under way. As one of Ray's former lawyers, Jack Kershaw, swore at the 1999 King V. Jowers civil trial (in which the jury found “governmental agencies” partly responsible for the assassination), Huie phoned him and offered Ray a large sum of money to confess and explain “how he killed by himself – he and he alone killed—shot and killed Martin Luther King...And I immediately asked him, what good is the money going to do this man? He's in the penitentiary. And Mr. Huie said, well, we'll get him a pardon immediately...he was very confident. I suggested he arrange the pardon before the story, but he didn't agree to that.” ("The 13th Juror: The Official Transcript of the Martin Luther King Conspiracy Trial", pgs. 393-394) Kershaw passed the offer on to Ray and Ray turned it down flat. As Ray noted in his book, when he mentioned the “offer” to his brother Jerry and attorney Mark Lane, Lane suggested Jerry should phone Huie “and ask him to be more specific—taping the conversation for safety's sake.” In two recorded conversations, “Huie said if I would, in effect, confess to the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., he'd come up with $220,000 for me, plus parole, which Huie claimed he could 'arrange' with Tennessee Governor Ray Blanton...As for the source of the $220,000, Huie wouldn't say. He knew better than to name his paymasters.” (James Earl Ray, "Who Killed Martin Luther King?", p. 201)

George McMillan

The name George McMillan will no doubt be familiar to students of the Kennedy assassination as the husband of CIA “witting collaborator” Priscilla Johnson McMillan. Priscilla, who had applied to work for the Agency but apparently became one of its media assets instead, authored Marina Oswald's “autobiography” "Marina & Lee"—a book Marina herself would characterize as “full of lies.” But it's not George's obvious ties to the intelligence community that discredit his book, "The Making of an Assassin", so much as it is his self-admitted willingness to knowingly publish falsehoods.

Jerry Ray, James' brother, was a major source for McMillan and, as McMillan knew full well, he made up just about everything he told him for money. As Harold Weisberg wrote, “All the Rays to whom McMillan spoke and whom he quoted denounced the book as full of lies (no small quantity of which were made up by Jerry Ray to fleece McMillan).” (Weisberg, "Whoring with History", unpublished manuscript, chapter 14) When he had gotten all the money he thought he was going to get from him, Jerry wrote to McMillan's publisher Little, Brown, and warned them “There isn't a word of truth in his whole book.”(ibid) On one occasion, when McMillan was desperately seeking a picture of the Ray family, Jerry procured some faded old photographs from an antique shop for a dollar and sold them to McMillan for $2,500. (Mark Lane & Dick Gregory, "Murder in Memphis", p. 240) “Of course he lied to me,” McMillan admitted, ( p. 234). But he went ahead and included the false information in his book anyway. And, according to Jerry Ray, he made up a few quotations of his own.

To typify McMillan, when Mark Lane phoned him and asked him if he had any recordings of his interviews with Jerry, or if he denied making up quotations, McMillan refused to answer (Lane and Gregory, pgs. 236-237)

Gerold Frank

On March 11, 1969, FBI deputy director Cartha DeLoach wrote the following in a memo to associate director Clyde Tolson: “Now that Ray has been convicted and is serving a 99-year sentence, I would like to suggest that the Director allow us to choose a friendly, capable author, or the "Reader's Digest", and proceed with a book based on this case.” The following day, as an addendum to this memo, DeLoach recommended “...author Gerold Frank...Frank is already working on a book on the Ray case and has asked the Bureau's cooperation on a number of occasions. We have nothing derogatory on him in our files, and our relationship with him is excellent.” Needless to say, the book that resulted from this “excellent” relationship, "An American Death", is cut from precisely the same cloth as Huie's and McMillan's, and Frank proves more than capable of spinning a tale or two.

Frank writes of an alleged incident from James Earl Ray's time in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, when Ray was drinking at a brothel with a prostitute calling herself “Irma La Deuce.” A group of sailors were drinking at a nearby table and one of the four black members of the party was laughing so noisily that Ray became incensed, telling La Deuce—also known as Irma Morales—that he hated blacks. Ray went over to the table, insulted the man, and went outside to his car. When he came back in, he stopped to insult the black sailor some more before going back to his table. He called Morales' attention to the fact that he now had a pistol in his pocket and that he wanted to kill the blacks. When the party left, Ray wanted to go after them but abandoned the idea after Morales mentioned it was almost time for the local police's 10 pm visit. (Frank, pgs. 304-305) When the HSCA tracked down Morales they found that Frank's version of events was a little out-of-line with the truth. What had actually occurred was that one of the black sailors had drunkenly stumbled as he walked past them and touched Morales in an effort to break his fall. The drunken Ray overreacted and become angry out of jealousy and had “never mentioned his feelings about blacks” to Morales. (HSCA report, p. 329) It might have been a pack of lies but I'm sure the FBI much preferred Frank's distorted version of events.

Wexler and Hancock must be aware of Frank's credibility problems. I was disappointed to find that they do, in fact, admit that documents show he was the author chosen to write the book the FBI wanted written, but they frequently used him as a source anyway. But yet a genuine authority on the subject like Harold Weisberg is completely ignored by the authors. This preference for sources that support the official story, which also includes Gerald Posner and Jim Bishop, has a reflective effect on the credibility of their own book.

I

The main thesis of "The Awful Grace of God" is that the forces behind the murder of Dr. King were members of a wide-ranging, white supremacist/terrorist network, hell-bent on sparking off a race war. This network included members or affiliates of groups like the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and the National State's Rights Party. The first seven chapters of the book are dedicated to identifying the most violent, outspoken, and influential members of this alleged network and detailing the numerous attempts they allegedly made, or planned to make, on Dr. King's life. Including attempted bombings and a planned sniper attack in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. The authors contend that these militant racists began reaching outside of their own groups and offering bounties of up to $100,000 to anyone who could get the job done. Much of the information provided is genuinely fascinating and many readers will likely agree that Wexler and Hancock have identified a number of possible suspects. But suspicion is not enough. For this to have relevance to the actual assassination, Wexler and Hancock need to prove that James Earl Ray had ties to one or more of these far-right organizations. Or that he heard about one of the alleged bounties and planned to collect it. Unfortunately, they cannot even come close to doing so.

The HSCA rejected racism as Ray's motivation for supposedly killing King and so too do Wexler and Hancock. But the authors understand full well that if he had held racist views and had racist contacts he would have been more likely to have been in the company of those discussing the alleged bounties on King. So they write that although Ray “was not fundamentally driven by racism” he nevertheless “wanted no part of blacks” and “opposed integration and the entire civil rights movement.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 160) In support of this claim, the authors, like George McMillan and Gerald Posner before them, cite the word of Ray's “fellow inmates” at Missouri State Penitentiary. As I see it, this represents an obvious double-standard on the part of the authors since they use Ray's background as a petty crook to undermine his credibility and yet are happy to accept the self-serving word of his fellow convicts, many of whom were paid informants or were seeking relief from lengthy sentences. Can there be any less trustworthy sources? In truth, there is no credible evidence that Ray was a racist or “wanted no part of blacks”. And as far as this reviewer is aware no one has ever come forward claiming they were racially abused by Ray. As William Pepper reported, “He evinced no hostility towards blacks whatsoever and his employers at the Indian Trails restaurant in Illinois had said he got along very well with his fellow workers, most of whom were minorities. They were sorry to see him go.” (Pepper, "Orders to Kill", p. 186)

In their attempt to establish Ray's racist tendencies and associations, Wexler and Hancock try to create the impression that he was politically active on behalf of Alabama governor George Wallace, a staunch segregationist. Writing that he “recruited associates to register to vote and support the Wallace campaign” in California. (Wexler and Hancock, p. 160) In truth, Ray made only a single known trip to Wallace's campaign office, so that three associates could register. But Ray himself never did under any of his aliases. And as Harold Weisberg discovered, no one associated with Wallace's California campaign knew or associated with Ray and “a thorough check of their files showed no sign of any of the names associated with” him. (Weisberg, "Frame Up", p. 360) Ray himself commented on the absurdity of claims that he was a political activist for Wallace: “I was a fugitive, hiding out. I wasn't crazy enough to become active in a political campaign.” (Lane & Gregory, p. 249) The fact is, despite an abundance of speculation, multiple “may haves”, “could haves” and “most likelys”, the authors never come any closer than this to placing Ray in the company of the type of extreme-right individuals they contend masterminded the assassination.

Wexler and Hancock believe that the Missouri State Penitentiary is one place in which Ray could have learned of a bounty being offered on Dr. King. They write matter-of-factly that the HSCA “seriously investigated one lead regarding a bounty offer that did reach Ray while in prison” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 163). But in using the word “did” the authors are apparently much more certain than the committee ever was. In fact, the HSCA only claimed to have found a “likelihood that word of a standing offer on Dr. King's life reached James Earl Ray prior to the assassination”. They then admitted that due to a “failure in the evidence” it “could not make a more definite statement.” (HSCA Report, p. 373) And even the HSCA's words were more certain than they had any right to be. Not only did the committee uncover no evidence that the alleged bounty reached Ray, it heard compelling testimony that called its very existence into question.

The HSCA's story of a bounty offer began with a March 19, 1974, report from an FBI informant concerning a conversation he had with a St. Louis criminal named Russell Byers:

"(Portion redacted) Beyers [sic] talked freely about himself and his business, and they later went to (portion redacted) where Beyers told a story about visiting a lawyer in St. Louis County, now deceased, not further identified, who had offered to give him a contract to kill Martin Luther King. He said that also present was a short, stocky man, who walked with a limp. (Later, with regard to the latter individual, Beyers commented that this man was actually the individual who made the payoff of James Earl Ray after the killing.) Beyers said he had declined to accept this contract, he did remark that this lawyer had confederate flags and other items about the house that might indicate that he was 'a real rebel'. Beyers also commented that he had been offered either $10,000 or $20,000 to kill King."

For whatever reason, despite the reference to a fictitious “payoff” to Ray, the committee took this report seriously and contacted Byers only to find that Byers denied the offer ever took place. After talking to his lawyer, Byers decided he would “cooperate”, but only under subpoena and with a grant of immunity which the committee gladly delivered. Now, probably hoping he was safe from prosecution for perjury, Byers named the two men at the alleged meeting as former stockbroker John Kauffmann and lawyer John Sutherland—both conveniently deceased by the time he was questioned by the HSCA. Presumably realizing that $10,000 or $20,000 was a fairly paltry sum, Byers also upped the amount he said he had been offered to $50,000. (HSCA Report, p. 360)

In order to establish whether or not the alleged Sutherland-Kauffman offer ever reached Ray, the HSCA examined “four possible connectives” none of which panned out. (pgs. 366-369) Thus the committee was forced to admit that “Direct evidence that would connect the conspiracy in St. Louis to assassination was not obtained.” (p. 370) Unperturbed, Wexler and Hancock claim there is “independent corroboration from another inmate named Donald Mitchell for Ray's knowledge of the offer.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 164) Indeed, on September 30, 1968, Mitchell did tell the FBI that some “friends in St. Louis” had “fixed it with someone in Philadelphia” for Ray to kill King and he offered to split the $50,000 he was to be paid with Mitchell if he would act as a decoy. But Mitchell was not done. He also claimed that after picking up the $50,000 for killing Dr. King, they would be picking up another payment for killing “one of those stinking Kennedy's.” (13 HSCA 248) Not surprisingly, the HSCA took Mitchell's claims with a grain of salt and his name does not appear in its report.

The HSCA was obviously unable to question Kauffman or Sutherland to confirm Byers' story and was unable to identify the “secret southern organization” supposedly financing the job. In fact, it found no substantiation for the existence of the supposed bounty beyond Byers' dubious word. On July 26, 1978, "The New York Times" reported of an interview with Kauffman's widow in which she told them “it was 'absolutely impossible' that her husband could have been involved in such a matter...and she believed that Mr. Byers had fabricated the information about her husband to 'help himself out of the art case.'” (Byers had been implicated as the buyer of stolen goods following the theft of a well-known bronze sculpture, but prosecutors later dropped the charges.) But the most damning information concerning Byers’ motivation for concocting the story came from a former lawyer, Judge Murray L. Randall, who had previously represented him in a civil case.

Byers told the HSCA that he had spoken of the alleged bounty with two lawyers, Randall and Lawrence Weenick. When contacted, Randall confirmed that Byers had indeed given him the story sometime “near the end of my law practice. I terminated my law practice November 4, 1974.” (7 HSCA 208) This, of course, would have been just after Randall gave the story to an FBI informant. As Randall explained, before the bounty conversation, sometime in 1973, Byers had spoken to Randall about a man named Richard O'Hara who was charged as an accessory to a jewel theft. Because the charge was “nolle prossed”, and because Byers was questioned by the FBI about something only O'Hara knew, Byers asked Randall “is Richard O'Hara the informant in this case”? Randall said he didn't know. After Byers gave his executive session testimony to the committee, Randall was contacted by Carter Stith, author of the aforementioned "New York Times" piece. Stith asked him if he had been the informant who gave the bounty story to the Bureau. Disturbed by this, Randall met with Byers and asked him “if he could tell from the report who the informant was and he said yes...He told me it was Richard O'Hara, said he could tell from the context.” (Ibid, p. 217) And yet, when Byers was asked by the committee if anyone else knew about the alleged bounty, he did not name O'Hara. As Randall concluded, and is most likely the case, Byers had concocted the entire story to smoke O'Hara out. Although the HSCA downplayed the significance of Randall's testimony, it uncovered nothing that invalidated his conclusion and, all things considered, it makes perfect sense. This would explain why the FBI did not act on the report in 1974 and why it made no move to question Byers: the Bureau knew what his game was and was therefore protecting its informant. It made no move to investigate the story because there was no need; Byers' bounty was a fabrication. It should be obvious then that Wexler and Hancock's assertion that the offer “did reach Ray while in prison” is simply not supportable.

The authors make a sizeable blunder when they write that after Ray's escape from Missouri State Penitentiary, and before he left for Canada in July of 1967, Ray “very likely heard more gossip about” the King bounty “at his brother's Grapevine Tavern in Saint Louis.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 249) Despite their claim, this is not “very likely” at all. In fact, it is downright impossible for Ray to have heard any gossip of any kind in his brother's tavern at that time. It is true that after he quit his job at the Indian Trails restaurant in Chicago on June 25, Ray did spend a few short weeks in the St. Louis area but he could not have spent any of that time at the Grapevine Tavern. Had Wexler and Hancock been a little more careful in their research, instead of clutching at straws to substantiate their theory, they might have discovered that Carol Pepper, Ray's sister, did not even take out a lease on the property until October 1, 1967. And that the bar did not officially open until January 1, 1968! (See FBI MURKIN Central Headquarters File, Section 34, pgs. 290-293 and 8 HSCA 537)

Not only does the book fail to establish that Ray was ever in a position to hear about a genuine bounty being offered for the murder of Dr. King, it also struggles to convincingly explain why he would be interested in taking up such an offer if he had. After all, Ray had no history of violent crime—the only person ever hurt during Ray's petty robberies was Ray himself—and he was certainly no gun-for-hire. What then would possess an escaped convict, whose only desire was to get out of the country and settle somewhere safe from extradition, to become involved in a crime of such magnitude? According to Wexler and Hancock, it was all about the cash. They write that if nothing else, “the individuals who knew him best were in agreement on what had driven James Earl Ray throughout his life: money.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 147) But if this were the case, then why did Ray turn down the aforementioned offer from William Bradford Huie of $220,000 and a pardon, when he all he had to do was admit to committing a crime for which he had already been convicted? The authors don’t reveal that Huie's offer took place. Therefore, they don't have to answer that question.

II

In his foreword to the volume, historian Gerald McKnight writes that Wexler and Hancock “do not pretend to fully resolve Ray's actual role, while considering arguments both for and against his possible act as Dr. King's killer.” (p. 7) Whilst this is technically true, there is nothing in the book that leads me to believe the authors ever considered his possible innocence or gave any serious thought to what role he might of played other than that of the gunman. They make passing reference to the idea that one particular alleged bounty offer (not the one they say Ray heard of in prison) “included two different options...one of which was money to simply track King and case his movements” (p. 216). But I'm sure the authors do not seriously expect readers to believe that Ray thought he was going to pick up $50,000 or $100,000 just for keeping tabs on Dr. King. (Recall, the large amount of money in the offer was supposed to be his motivation). Also, such a role would be at odds with his purchase of the 30.06 Remington Gamemaster rifle that the authors maintain he had in his possession on April 4, 1968.

Wexler and Hancock present “three possibilities”. Two of these involve Ray as the shooter. None of them consider the possibility that Ray played no knowing role in the assassination conspiracy and was merely an unwitting patsy as he always maintained. Under the heading “Narrowing the Possibilities”, the authors present their preferred scenario in which “something unplanned happened in Memphis” and Ray, who “may have only agreed to participate in surveillance and support”, probably shot King on the spur of the moment. (pgs. 243-248) But this is far-fetched and does not align with the record. For if Ray had taken up a “surveillance” role, with no plans to do the shooting, then why did he purchase the rifle? And further, as Wexler and Hancock contend, carry it into the bathroom of the boarding house? A high-powered rifle is not an essential tool for surveillance. The authors do not address this inconsistency. In any case, regardless of what Wexler and Hancock consider to be a “possibility”, there is not any credible evidence that the shot that killed Dr. King was fired from the bathroom window; let alone that Ray fired it.

To be fair to the authors, they do note some of the problems with the evidence against Ray. But it has to be said that they omit—knowingly or unknowingly—that which tends to prove his innocence. For example, nowhere in book will the reader find mention of the fact that there were two white Mustangs outside the boarding house that day; that one of them was seen leaving the scene shortly before 6:00 pm, right around the time Ray said he left Brewer's flophouse to get his spare tire fixed; and the other left within a minute or so of the assassination. If indeed the one departing before 6:00 pm was Ray's Mustang, as the evidence suggests it was, then it is without question that he was not the assassin and was framed by an orchestrated conspiracy. Understanding its significance, establishment authors like Gerald Posner generally deny the existence of the second Mustang, dismissing it as myth-making by conspiracy theorists. But as author Harold Weisberg pointed out, the Associated Press reported its presence in April 1968. In fact, the "Memphis Commercial Appeal" published a diagram of the crime scene showing the two white Mustangs parked on Main Street. (Weisberg, p. 183) This would not have been an uncommon sight in Memphis in 1968. Frank Holloman, director of Memphis police and fire departments, stated that there were “a large number of white Mustangs” in the area and police estimated they had stopped 50 to 60 in the aftermath of the shooting. (Philip Melanson, "The Martin Luther King Assassination", p. 114) According to the April 14, 1968, "Minneapolis Tribune", “White 1966 Mustangs are plentiful in Memphis. In fact, a Ford dealer estimated 600 of them were sold and 400 are still on the street.” (Weisberg, p. 181) At the television trial of James Earl Ray, former FBI Special Agent Joe Hester conceded the presence of two white Mustangs at the crime scene and unsurprisingly dismissed it as a “coincidence.” (Pepper, p. 286)

Ray always maintained that he parked his car directly in front of Jim's Grill. And a number of witnesses including David Wood, Loyd Jowers, and William Reed confirmed that a white Mustang was indeed parked in that location. At the same time, the other white Mustang was parked several car lengths south, near the doorway to Canipe's Amusement Company. There it was seen by employees of the Seabrook Wallpaper Company located across the street. (Melanson, pgs. 114-116) Charles Hurley parked behind this Mustang at approximately 5:00 pm when he arrived to pick up his wife Peggy, who was working at Seabrooks. He noted that it had Arkansas plates. Ray's were from Alabama. (Pepper, p. 156)

Perhaps the two most important witnesses were Ray Hendrix and William Reed. They exited Jim's Grill somewhere around 5:30 pm. When Hendrix realized he had forgotten his jacket, he went back inside the grill to collect it while Reed stood outside checking out the white Mustang parked out front. When Hendrix reappeared, the two men walked north along Main Street until they came to the corner of Main and Vance. Just as they were about to step off the curb, a white Mustang rounded the corner in front of them. Reed could not say for certain this was the same car he saw in front of Jim's Grill but said “it seemed to be the same” one. (13th Juror, p. 352) Because witness statements establish that the Mustang outside of Canipe's left a minute or two after the assassination, it appears most likely that the one Hendrix and Reed saw pulling onto Vance was indeed the one previously parked outside Jim's Grill—right where Ray said he had parked his white Mustang. And because Hendrix and Reed's recollections dovetail with the 5:30 to 6:00 time frame in which Ray said he went to get his tire fixed, it appears that they corroborate Ray's alibi and thus provide strong evidence of his innocence. And yet, as I mentioned above, none of this appears in "The Awful Grace of God" and instead the authors assert matter-of-factly that “Ray sped off in his white Mustang” after the assassination. (Wexler and Hancock, p. 223)

One of the biggest problems with the State's case has always been the inability to match the bullet removed from Dr. King's body to the rifle Ray purchased. Predictably, Wexler and Hancock appear to accept the FBI's claim that the problem lay in the “distortion and mutilation” of the bullet. But the authors do not mention the fact that some of that mutilation happened while the slug was in Bureau hands. As pathologist Dr. Jerry Francisco testified at the 1999 civil trial, when he removed the bullet from the body at autopsy it was in one piece. (13th Juror, p. 245) But by the time the FBI was through with it, however, it is was in three separate fragments. (13 HSCA 77) But even then, according to world-renowned forensics expert and professor of criminalistics Herbert MacDonnell, identification should have been possible. In 1974, MacDonnell was contacted by Ray's defense team and asked to examine the physical evidence in the case and testify at Ray's evidentiary hearing. After viewing the bullet he remarked to Harold Weisberg—who was then the team's sole investigator—“I wish I had that good a specimen in most of my cases.” (Weisberg, "Whoring with History", Chapter 24) When he took the stand the following day, MacDonnell testified that he had found “sufficient detail” that “identification ought to be possible” (ibid) and McDonnell was not alone in his belief; ballistics experts Lowell Bradford and Chuck Morton agreed. (ibid , see also, Pepper, p. 267) Wexler and Hancock omit any mention of these expert opinions and instead write that the HSCA firearms panel “could not find conclusive matches” between test bullets and that therefore, “any further testing between the actual assassination bullet and a test slug was fruitless, as the very basis for any such test was eliminated.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 289) But this ignores the fact that further tests were conducted years later and, although the results were again inconclusive, a possible explanation for the outcome was offered.

In 1994, Judge Joe B. Brown granted a request by William Pepper, Ray's final attorney, for further testing of the rifle and bullets in evidence. Brown, himself a ballistics expert, testified as to the results at the 1999 civil trial. Judge Brown explained that 18 test bullets were fired and that 12 of those bullets showed a similar “unusual characteristic”—a bump on the surface—that appeared to be the result of “shattering in the tool” used to make the barrel. Upon inspection of the barrel, Brown discovered that it was “absolutely filthy” with jacket powder and concluded that it was this build up that was causing the inconclusive results. As he put it: “Now, because this weapon was not cleaned, what happened was that the filing material was being blown out of this flaw. So one of these bullets would have a gross reflection of this flaw. The next shot through it would be somewhat less impressed because of the filing that had filled up this defect. The third one would have even less of an impression. Then the filing would get blown out. The next bullets through would not show it to a gross extent. So you've got twelve bullets with the same common characteristic, that is, this raised area on the surface of the bullet...that was not found on the corresponding portion of the bullet removed from Dr. King.” (13th Juror, pgs. 235-236) In an attempt to solve the problem, Judge Brown ordered the rifle cleaned with an electrolysis process using a chemical solution. This would remove the filings without harming the barrel itself. At that precise point, a plot was hatched in Memphis to get Brown removed from the hearing. (For the details of how this plot was implemented, see "The Assassinations", edited by James DiEugenio and Lisa Pease, pgs. 449-60) Ultimately, the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals had him removed from the case, claiming that he had lost his objectivity. Whilst this decision left the results far from definitive, it is clear that the outcome of this round of tests was consistent with the proposition that a different 30.06 rifle was used to fire the death slug.

III

Not only do Wexler and Hancock fail to mention Ray's possible alibi or relate that further ballistic tests were performed—and halted by a state determined to preserve the cover-up—but they also take for granted that the shot was fired from the bathroom. Ignoring the fact that there is at least as much evidence indicating that it actually came from the bushes below. The authors do note that the path of the bullet was not fully traced at autopsy, and that the HSCA trajectory analysis found that “the geometric data was consistent with either the second-floor rooming house windows or the ground-level shrubbery below” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 239). But this is their only reference to the area that has long been suspected as the actual source of the shot. Suspicions about the bushes began with the April 4, 1968, account of Dr. King's chauffeur, Solomon Jones. He was standing below the balcony talking to King when the shot rang out. He told Memphis police that evening that after King fell, he “ran to the street to see if I could see somebody and...I could see a person leaving the thicket on the west side of Mulberry with his back to me. Looked to me like he had a hood over his head...something that was fitting close around his shoulders and was white in color...he appeared to be a small person and was moving real rapidly.” That this person running from the bushes may have been the actual assassin is indicated by the account of Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) member, Reverend James Orange. Moments after the shot, Orange noticed “smoke came up out of the brush area on the opposite side of the street from the Lorraine Motel. I saw it rise up from the bushes over there. From that day to this time I have never had any doubt that the fatal shot...was fired by a sniper concealed in the brush area...” (13th Juror, p. 288) The names of Solomon Jones and James Orange do not appear in The Awful Grace of God.

Of course, this is not definitive evidence that a shot came from the brush below. Not at all. But the reader should bear in mind that there is no credible evidence to support the contention that the shot came from the bathroom of the rooming house. There was not a single witness who claimed to have seen a gunman in the bathroom window, nor was there a witness to a rifle or smoke coming out of that window. And no one ever claimed to have seen a man with a rifle going into or coming out of the bathroom. Memphis police officers discovered a dent on the bathroom windowsill and it was claimed that this dent was made when the sniper rested his rifle there and took his shot. Wexler and Hancock label this contention as “more than questionable” (p. 240). But this is actually a vast understatement because this claim is unquestionably false. When the windowsill was cut out, the dent, which was on the inside half of the sill, was examined by the FBI. They found no “gunpowder or gunpowder residues” of any kind. Additionally, “No wood, paint, aluminum or other foreign materials” were found on the rifle; “nor were any significant marks found on the rifle barrel.” (Weisberg, Whoring With History, Chapter 23) In actual fact, not only was there no evidence that the rifle caused that mark, it would have been impossible for the rifle to have been rested in that dent and fired. According to Harold Weisberg, when Herbert MacDonnell examined the sill and then saw pictures “of how close that window was to the north wall of that bathroom he erupted with laughter because it was immediately apparent that it was impossible for the muzzle of that rifle to be in that dent and pointed at where King was, and for the entire rifle to be inside that bathroom! Part of the rifle stock and butt and of the rifleman would have had to have been inside the wall!” On top of this, as MacDonnell testified, with that dent being on the inside half, a shot from the rifle “would have torn up the windowsill.” (ibid, chapter 24)

When Paris-Match magazine attempted to simulate the assassin's alleged position, it ended up demonstrating how unlikely, if not impossible the official story is. Because the old fashioned bathtub in which the sniper is said to have stood was positioned against the east wall and had a steeply slanting back, the only way he would be able to fire on the required downward trajectory would be to stand on the rim of the tub. Not only did this put the shooter so high that he would have to turn his head on its right side and thus struggle to aim the rifle but it also meant that the barrel of the rifle would be sticking out of the window. (Click here for the picture, http://i1205.photobucket.com/albums/bb421/mnhay27/Scan10002.jpg)

The unlikelihood of this scenario is obvious. And it can be rightly said that the Paris-Match photo—in conjunction with the fact that Ray had an abysmal shooting record in the army, plus the fact that the Remingtom Gamemaster rifle was not properly sighted in—these all but destroy the State's case.

Steering well clear of this crime scene “morass” enables Wexler and Hancock to claim that, although it was never tested in court, “a substantial amount of evidence was assembled to place Ray at the crime scene, to connect Ray to the rifle, and to create a plausible description of the fatal shot having been fired from the rooming house bathroom.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 239) Which, in light of the above, is simply an untenable statement. Not only, as we have seen, is there no credible evidence that a shot was fired from the bathroom (and plenty of reason to doubt it was even possible); there is no credible evidence to place Ray at the scene of the crime, or put the rifle in his hands at the time of the assassination. Ray was adamant that he gave the rifle to the man he says set him up. This is a man he knew as “Raoul”. This was on the evening before the assassination and never saw the weapon again. Since no one saw Ray take a rifle into or out of the rooming house, there is no evidence to prove otherwise. There is also no evidence that he was ever in the bathroom; none of Ray's fingerprints were found anywhere in the rooming house and no witnesses saw him going into or emerging from the bathroom at any time. The State was so bereft in this regard that it was forced to rely on the account of an alcoholic named Charles Stephens who occupied the room between the bathroom and the one Ray had rented that afternoon. Stephens told police that after he heard the shot, he opened his door and saw a man running down the hall, holding something wrapped in newspaper, and heading towards the front stairway. Although he told police on the evening of April 4, 1968, that he would not recognize the man if he saw him again because he “didn't get that good a look at him”, Stephens would subsequently identify that man as James Earl Ray. Stephens would be instrumental in Ray's extradition following his arrest in London. Because numerous witness statements establish the fact, Wexler and Hancock admit that Stephens “was almost certainly too drunk to be credible” (p. 240). But they withhold that which is most damaging: On April 18, 1968, Stephens was shown a picture of Ray by CBS news correspondent Bill Stout and was asked if it showed the man he saw in the rooming house. On camera, Stephens proclaimed, “...that definitely, I would say, is not the--the guy.” Definitely not the guy! And, whether Wexler and Hancock want to admit it or not, Stephens and Stephens alone represents the “substantial amount of evidence” they claim places Ray at the crime scene.

IV

Until the day he died, James Earl Ray claimed that he had been set up in the assassination by a mysterious figure he knew only as “Raoul.” The pair had met at a place called the Neptune Bar in Montreal, Canada, in July of 1967. Having escaped from prison, Ray was seeking identification papers and funds that would allow him to flee to a country with whom the United states had no extradition treaty. According to Ray, Raoul promised he would get him the necessary documents if Ray would help him with a few low-risk smuggling operations. For the next nine months Ray followed Raoul's orders. He delivered items into the United States and Mexico, and in return received substantial sums of money. Under Raoul's directions, he acquired a new car—the white Mustang—purchased a rifle, and exchanged it the following day for the 30.06 Gamemaster. He then ultimately rented a room in Bessie Brewer's rooming house opposite the Lorraine Motel where King was staying in Memphis. As Mark Lane noted, “Ray's explanation...of his movements through the United States from Canada to Mexico, his purchase of a rifle in Birmingham, and ultimately his presence in Memphis on April 4th in the vicinity of the murder scene is either basically true, or the intricate and comprehensive work product of a brilliant mind. For the narrative explains in a cohesive fashion all of Ray's otherwise inexplicable actions.” (Lane and Gregory, p. 173) Few people would claim that Ray was the owner of a “brilliant mind”. After all, this is the same bungling crook who once took his shoes off whilst attempting to rob a store, and had to take off in his stocking feet when he was panicked by the sight of policemen outside. Ray ran for miles before heading back to town wearing a pair of women's shoes he had picked up along the way because he did not want to look conspicuous! (Pepper, p. 187) Nevertheless, the official position is that Raoul never existed and I'm sure by now the reader will not be surprised to learn that Wexler and Hancock subscribe to this view.

The authors suggest that Ray concocted the Raoul character for protection, writing that “Ray simply would not have directed attention to individuals or groups that might prove personally dangerous to him in prison.” (Wexler and Hancock, p. 161) Whilst this argument may make a little sense when considering Ray's predicament in 1968 (although I seriously doubt he would have been refused special protection for telling all he knew and fingering the actual culprits), it is less convincing when we remember that he was still telling the same story three decades later when the power and influence of groups like the KKK and NSRP had long since diminished or evaporated entirely. In actual fact, the NSRP had ceased to exist entirely by the late 1980s. There can be little doubt that by sticking by his Raoul story Ray kept himself locked up for life by a disbelieving State. But stick to his story he did.

In support of their argument that Raoul did not exist, or was a “composite” of individuals Ray dealt with in the lead up to the assassination, Wexler and Hancock cite Ray's “constant changes in Raoul's physical description, which varied to include an auburn haired man, a thirty-five-year-old blonde Latino, and a reddish-haired French-Canadian, with complexions that ranged from ruddy to dark to lighter than Ray's own pale skin.” (p. 170) It is difficult to respond fully to this because the authors do not provide a single citation for any of these descriptions. What is known is that at least one of them—that of a “blonde Latino”—came not from Ray, but from William Bradford Huie who's credibility, as we've already established, is less than zero. (That description certainly does not appear in the “20,000” words written by Ray that Huie's own writing was supposedly based on). Another one, the lighter than Ray's own complexion description, comes from a misreading of one of Ray's testimonies that was cleared up when he appeared before the HSCA. Committee chairman Louis Stokes asked Ray “Have you also at some time or other described Raoul as having a complexion lighter than my own?” to which Ray replied, “No, I never gave that description.” At that point, Stokes referred Ray to an extract from his lawsuit against Percy Foreman in which he described Raoul as “5 foot 10, a little bit lighter than me and dark haired.” As Ray explained, as the HSCA accepted, and as is perfectly obvious from his testimony, he was referring not to Raoul's complexion but to his weight. (1 HSCA 359-366) As I wrote above, with no citations provided, it is simply not possible to respond in full to Wexler and Hancock's claims. But what I can say is that although plenty of unreliable writers have made claims to the contrary, in every recorded interview with Ray, every sworn testimony, and in every writing from his own hand that this reviewer has come across, Ray has always been consistent in his descriptions of Raoul.

One problem facing those who maintain that there was no Raoul is explaining the large sums of money Ray clearly handled whilst having no official source of income. Ray said that he had only $300 dollars to his name when he escaped prison but Wexler and Hancock do not want to believe this, so they repeat the indefatigable George McMillan's fable that Ray probably made as much as $7,000 in prison “selling magazines, black market items, and possibly small amounts of amphetamines.” (Wexler and Hancock, pgs. 156-157) As with most things McMillan, this claim has no basis in fact. It was just another story Jerry Ray fed him for cash. After McMillan's book was published, Missouri Corrections Department chief George M. Camp challenged the author to provide proof of his “totally unsubstantiated” allegations and publicly demanded that he “either put up or shut up.” (Pepper, p. 62) Wexler and Hancock are apparently aware of this so they do some CYA by writing that the amount of money Ray had upon escaping prison is “in dispute”. (See p. 166) But they take another stab at explaining Ray's finances by raising the “possibility” that Ray and his brothers were involved in the July 1967 robbery of the Bank of Alton in Illinois. Ibid, p. 168) This story was embraced by the HSCA. They tried to persuade the Justice Department to charge John Ray with perjury for supposedly giving false testimony concerning the robbery. Justice wrote back to the committee stating that “there is no evidence to link John Ray or James Earl Ray to that robbery” and declined to consider any prosecution. (Pepper, pgs. 108-109)

The Justice Department was correct: there was no evidence that the Ray brothers were involved. In July of 1968 the FBI had compared James Earl Ray's fingerprints to those from all unsolved bank robberies, including the Alton one. They found no matches. In August 1978, when the HSCA was selling its bank robbery story to the press, Jerry Ray surrendered himself to the Alton police department. He offered to waive the statute of limitations and be charged with the crime. As he recalled in his testimony at the 1999 civil trial, the police asked him “are you here to confess to the crime? I said I can't confess to a crime that I didn't commit, but Congress accused me of committing a crime so I'm here to stand trial. He said you never was a suspect.” (13th Juror, p. 343) In a follow-up phone call three months later, attorney William Pepper was told by East Alton police lieutenant Walter Conrad that neither Jerry “nor his brothers were suspects, nor had they ever been suspects in that crime.” (Pepper, p. 108) Needless to say, none of this is mentioned in The Awful Grace of God.

Wexler and Hancock also omit any mention of the former British merchant seaman Sid Carthew. Carthew came forward after Ray's televised mock trial in 1993. His testimony supported the existence of Raoul. For months after it aired, Carthew was watching a video tape of the TV trial “…and it came up on the court scene where the prosecutor was ridiculing James Earl Ray and saying that this Raul was a figment of his imagination, and I called my daughter in the room and said, look, no, this isn't a figment or lie. I said, this poor man is telling the truth...” Carthew went to some lengths to contact Ray's defense to tell what he knew. He eventually gave his story to William Pepper in a sworn deposition. According to Carthew, he too had met a man identifying himself simply as Raoul in the Neptune Bar, Montreal, in 1967. Over the course of two evenings, Raoul had offered to sell him some Browning 9mm handguns. “He said to me, how many would you want, and I said four...and he said, four, what do you--four, what do you mean by four. I said four guns. He wanted to sell me four boxes of guns...once he knew that I would have only take--took four, he was very annoyed...it wouldn't be worth his while to deal in such a small number, and that was the end of the conversation, and he went back to the bar.” (13th Juror, pgs. 270-277) Carthew's account received partial corroboration from a shipmate of his named Joe Sheehan. He said that, although he wasn't present at the Neptune bar, Carthew had mentioned the incident to him in May 1968 at the annual general meeting of the National Union of Seamen. (Pepper, p. 344) If Wexler and Hancock are privy to any information which disproves Carthew's sworn account, they do not share it with their readers.

V

Dismissing Raoul as a “red herring” leaves Wexler and Hancock free to repeat the age-old myth that Ray was stalking Dr. King in the weeks before his assassination. They write that there is “no sign he was tied into a King conspiracy” until mid-February 1968. Then, they perceive a “change in behavior” showing that Ray “was responding to what he felt was finally a truly concrete bounty offer on Dr. King's life.” Then, on March 17, “he completed a change-of-address form forwarding all his mail to general delivery, Atlanta, Georgia”, Dr. King's home town. He then presumably set off from his current residence in Los Angeles to begin stalking his prey. (Wexler and Hancock, pgs. 200-203)

What the authors are careful not to reveal is the uncontested fact that, if Ray wanted to surveil Dr. King, he was heading in completely the wrong direction because King was in Los Angeles! On March 16th, King had given a speech to the California Democratic Council at the Disneyland Hotel in Anaheim. On March 17th he delivered a sermon at a church in Los Angeles. This information would, I'm sure, have given most readers cause to seriously question the notion that Ray had King in his sights on March 17th. But you will not find it in this book.

The authors claim (incorrectly) that “Ray's path first crossed Dr. King's on the night of March 22, 1968, in Selma Alabama.” (Ibid, p. 217) I say this is incorrect because, as Wexler and Hancock themselves write, King and Ray were never in Selma at the same time. And, as noted above, their paths had actually crossed five days earlier in Los Angeles, where King followed Ray there, and Ray took off soon after he arrived. They also claim (incorrectly) that Ray initially “lied about his Selma stop, saying he had gotten lost between New Orleans and Birmingham”. But that “in his interview” with William Bradford Huie, “Ray finally admitted that he had gone there because of King.” (ibid) Firstly, as made clear before, Ray was never “interviewed” by Huie. Huie actually received his information either via Ray's attorneys, or through written notes which contain no such admission. Secondly, Ray never changed his story. He stuck to the “lost” explanation in his HSCA testimony and in his own written works. Self-admitted fabricator Huie just followed his usual practice and wrote what he wanted to regardless of what the truth was.

Wexler and Hancock also attempt to resurrect another time-worn fable dreamed up by Huie. Namely, that a map of Atlanta found amongst Ray's possessions after the assassination had marks on it “indicating King's residence, King's church, and the headquarters of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference”. The authors claim that the marks are “beyond coincidence”, quote Ray as admitting that he could never “explain that away to the jury”, and say that “the best he could come up with was that the marks represented restaurants he visited.” (Ibid, p. 222) As portrayed by Wexler and Hancock, this sounds like a damning admission and a lame excuse by Ray. But they achieve this by taking his remarks out of context. So that the reader can judge for himself, here are the relevant passages from Ray's HSCA interview:

Q. Well, why did you mark that particular map?

A. I marked where I was staying at. Places I came in, the highway I came in off of. Peachtree Street, where I went to the bank one time to cash in some money. I marked a restaurant on there and I think I glanced at it a few times to get my bearings on it and that was it. (9HSCA215)

Q. What other map do you recall marking?

A. I don't particularly recall marking, I don't even, the Atlanta map. I don't particularly recall marking that except that they made a big issue out of it and I started thinking about it. I would probably never recall all the details on that if I hadn't have tried to--Let me try to explain why. I don't know if you have read all these books or not. William Bradford Huie said he found the map in Atlanta somewhere in my suitcase. It had circles of Dr. King's church, his house, his office, and his ministry, his church or something, and I knew that was all false. I mean, I knew--I started thinking and I knew I marked, but I knew that would have been a coincidence. If I had marked all these places that would have been too big a coincidence. I could never explain that away to the jury. So, I got to thinking about it, and I gave it a lot of thought and that's the best I could come up with. Now, if you can look at that map get it from the FBI, I think that would settle that once and for all, if I marked anyone's church. (9HSCA224)

It should be pretty clear to the reader that Ray said the marks on the map represented more than just “restaurants he visited” and, despite the impression Wexler and Hancock attempt to convey, he never agreed that those marks showed what Huie claimed they did. In fact he explicitly stated that he “knew that was all false.” And false it was. As William Pepper explained to the jury at the 1999 civil trial, “Mr. Ray had a habit of marking maps. I have in my possession maps that he marked when he was in Texas, Montreal and Atlanta, and what he did was it helped him to locate what he did and where he was going. The Atlanta map is nowhere related to Dr. King's residence. It is three oblong circles that covered general areas, one where he was living on Peachtree.” (13th Juror, p. 741) Had the markings on the map revealed what Huie claimed, there can be little doubt that the HSCA would have made a big song and dance about it. As it was, the committee dismissed the relevance of the Atlanta map and made no reference to it in its report.

Wexler and Hancock claim to know for sure that Ray lied about his movements after he purchased the Remington Gamemaster rifle in Birmingham, Alabama, on March 30, 1968. Ray's story was that he made his way slowly to Memphis, staying at a motel near Decatur, Alabama on March 30; near the twin cities of Florence and Tuscumbria on March 31; at a motel near Corinth, Mississippi on April 1; and at the DeSoto Motel on Highway 51 near the Tennessee border on April 2. (Ray, p. 92) Huie claimed that he could find no evidence that Ray stayed at any of these establishments under any of his aliases. But Harold Weisberg had no trouble establishing that Ray had stayed at the DeSoto on April 2. When Weisberg visited the motel, he was shown the registration card bearing the “Eric Galt” alias Ray was using and spoke to one of the two maids who had worked that night and she confirmed his stay. “She told me”, Weisberg wrote, “that when they saw Ray's picture they recognized him as the man who had stayed there the night that had to have been of April 2.” (Whoring with History, Chapter 19) In any case, Wexler and Hancock follow the HSCA's lead and claim that a receipt and a counterbook from the Piedmont Laundry in Atlanta prove that he lied and was, in fact, back in Atlanta on April 1 dropping off laundry that he would pick up on April 5. When confronted with this evidence during his HSCA testimony, Ray stuck to his story and, on the face of it, it does appear as if he was caught in a lie. But, unfortunately, it is not that black and white. Firstly, the receipt is stamped “April 2” which would appear to indicate that the laundry was picked up the day after it was dropped off. And secondly, Piedmont worker Annie Estelle Peters was unable to positively identify Ray as the man who dropped off the laundry. In fact, when shown a series of pictures of Ray by the FBI in May 1968 she remarked that “none appeared very similar.” (FBI MURKIN Central Headquarters File, section 43, p. 27) So whilst it appears possible that Ray may have lied to cover-up what many would say was too big a coincidence, the evidence does not allow us to say he “definitely” did as Wexler and Hancock contend. (Awful Grace of God, p. 217) What is interesting to ponder is the fact that if Ray had concocted Raoul to lay the blame for the assassination elsewhere, and if he really had gone back to Atlanta, the easiest thing for him to have done would have been to have admitted he had done so and claim that he was only following Raoul's instructions. But he never did this.

VI

The final aspect of The Awful Grace of God that requires comment has to do with the authors' attempt to dismiss any notion of government complicity in the assassination. This they do in an appendix titled “Being Contrary”, which is likely to be one of the most controversial parts of the whole book. Hancock and Wexler find the idea of federal involvement “unconvincing” and claim that “many of the theories of government involvement are based on elements that appeared mysterious immediately following the assassination, but that have been explained through follow-up research in the ensuing years.” (pgs. 306-307) They list a number of points for which they present “counterarguments”, many of which are likely to spark debate—especially those involving the theories of William Pepper and the case put before the Memphis jury at the King V. Jowers civil trial. But the only part I wish to comment on has to do with Dr. King's location and security at the time of his death.

When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, in 1963, many critics wondered how he could have ended up in the position he was in. They argued that usual security protocols had been systematically violated and JFK had been driven slowly into a perfect ambush site without customary procedures such as having Secret Service agents on the running board of the limousine. And when these issues were raised, the victim was blamed. The Secret Service quickly spread the word that Kennedy himself had ordered agents and police motorcycles to stay away from the Presidential limo so that the public would have an unobstructed view. But the meticulous research of Vince Palamara has since proven this to be a tissue of lies constructed by JFK's security detail simply to cover their own asses. This curious set of circumstances very closely parallels events surrounding Dr. King's assassination: He was placed in room 306 of the Lorraine motel with access via an open and potentially dangerous balcony without his usual security. And his organization, the SCLC, was blamed for its removal.

Wexler and Hancock imply that Dr. King always stayed at the Lorraine when he visited Memphis and state that King and his closest companion, Dr. Ralph Abernathy, “had stayed in room 306 so often that it was jokingly referred to as the 'King-Abernathy Suite.'” (p. 17) Although they do not provide a citation, it appears they gathered this from Abernathy's HSCA testimony. Which, on the face of it, would seem to be a reliable source. But yet there is much controversy on this issue and Abernathy's recollection is contradicted by a number of people. For example, Reverend Jim Lawson, another close friend of Dr. King and a co-founder of the SCLC, testified that King “had stayed more often in the Admiral Benbow and in the Rivermont”. (13th Juror, p. 139) And Memphis reporter Kaye Pittman Black, who had “covered his every visit to this city”, believed that Dr. King “had never stayed at the Lorraine.” She recalled him staying “at the Claridge, the big hotel downtown, right across from City Hall.” (Lane & Gregory, p. 107) It is highly unlikely that Abernathy would have lied in his testimony so it would seem apparent that King must have stayed at the Lorraine on at least some of his visits to Memphis. But if at some point King had been in the habit of staying at the motel, it is clear that it was a habit he had broken. For on his March 18 visit to Memphis, King had stayed at the Rivermont Hotel (13th Juror, p. 292), and on his March 28 visit he and Abernathy had reservations at the Peabody Hotel. But they were taken to the Rivermont after the march they were leading had turned violent. (Pepper, Act of State, p. 188) Jim Lawson explained to attorney William Pepper that since the white-owned hotels were starting to be desegregated, “black leaders believed that they had an obligation to become guests and establish a presence in what had formerly been white lodging bastions.” (ibid) So, whether he had done so many times before or not, any conspirators planning to assassinate Dr. King on his return to Memphis had no guarantee that he would be staying at the Lorraine on April 4, 1968. But one very powerful and very hateful man seemingly had a plan to ensure that he would.

On March 29, 1968, J. Edgar Hoover's FBI headquarters issued a memorandum to be disseminated to “friendly” media sources:

"Martin Luther King, during the sanitation workers' strike in Memphis, Tennessee, has urged Negroes to boycott downtown white merchants to achieve Negro demands. On 3/29/68 King led a march for the sanitation workers. Like Judas leading lambs to slaughter, King led the marchers to violence, and when the violence broke out, King disappeared. The fine Hotel Lorraine in Memphis is owned and patronized exclusively by Negroes, but King didn't go there for his hasty exit. Instead, King decided the plush Holiday Inn Motel, white owned, operated and almost exclusively patronized, was the place to “cool it.” There will be no boycott of white merchants for King, only his followers."

Although they do not mention this memo, I'm sure Wexler and Hancock would argue that its purpose was simply to embarrass Dr. King. And maybe it was. But given that Hoover's well documented hatred of King is known to have led him as far as trying to pressure him into committing suicide, many researchers believe his intent was much more sinister. And this possibility becomes more compelling in light of the fact that an unidentified individual, claiming to be with the SCLC, contacted the Lorraine to insist that Dr. King be moved from the more secluded room 202, in which he was originally meant to stay, to the balcony room 306.

Former New York City police officer Leon Cohen testified in 1999 that Lorraine owner Walter Bailey had told him about the room change the day after the assassination. According to Cohen, Bailey explained that before Dr. King arrived on April 3, “he got a call from a member of Dr. King's group in Atlanta who wanted him to change the location of the room where Dr. King would be staying. And he was adamant against that because he had provided security by the inner court for Dr. King”. (13th Juror, p. 85) Sometime later, Bailey told reporter Wayne Chastain that it was actually his wife who had dealt with the SCLC man. (Act of State, p. 190) In any case, in 1992 William Pepper spoke to an employee of the Lorraine named Oliva Hayes who “confirmed that Dr. King was to be in room 202 but was somehow moved up to room 306.” (ibid) Now perhaps there is an innocent explanation for this room change but it is curious in the extreme that none of King's entourage owned up to ordering it and the “SCLC man” remains unidentified. Needless to say, this move allowed King to be exposed to a sniper from across the street.

Hoover's memo and the unexplained room change seem to take on added significance when we consider the unusual change in Dr. King's security arrangements. Another name not mentioned in "The Awful Grace of God" is that of Memphis Police Captain Jerry Williams who headed up a special security detail of black officers who were assigned to protect Dr. King on his visits to Memphis. Williams' unit had a good relationship with King's group and Reverend Lawson recalled being impressed when the officers introduced themselves and told him that “if Dr. King will cooperate with us...we can assure you that nothing will ever happen to Dr. King when Dr. King is in this city.” From then on, Lawson explained, “whenever he came to Memphis, that group of homicide detectives and other detectives were relieved of all their duty. They gave him 24-hour surveillance. They talked to his office and him about where you will be safest, where are the places he could be most secure.” (13th Juror, p. 133) But on King's final visit to Memphis, as Captain Williams testified, he was instructed that his unit would not be formed, that “somebody else would handle the assignment”, and he was not given an explanation for the change. (p. 105) When King's party arrived at the airport, instead of the usual group of black officers, they were confronted by a group of white detectives who it had to be obvious, given the tense atmosphere of the time, were simply not suitable. Within hours the detail was removed on the grounds that King's party was not cooperating and it is impossible to resist the urge to speculate that this is exactly what police had intended all along. Why else would they not send the usual unit of trusted black officers? A clue to an additional reason comes from Williams' testimony that his unit “would never advise him to stay at the Lorraine because we couldn't furnish adequate security.” (ibid)

As well as Dr. King's personal security detail, six Memphis Police Tactical Units were removed from the vicinity of the Lorraine on the morning of the assassination. According to Professor Philip H. Melanson, these were essentially “riot control units” that had been formed to patrol the area “within a five-block radius of the Lorraine Motel”. But on the morning of April 4, Inspector Sam Evans gave the order “for the tactical units to be withdrawn outside of a five-block area, therefore, dispersing them at a much greater distance and removing their presence from the immediate what would become the assassination scene.” When Melanson asked Evans why he had given this order, “He told me that he had been requested by a member of Dr. King's party to remove the units from proximity to the Lorraine Motel.” When Melanson asked for a name, Evans claimed that the request came from the Reverend Samuel Kyles. (p. 113) But Kyles was a local pastor who had no position in the SCLC, no authority to make such a request, and denied making it anyway. (Act of State, p. 234) As William Pepper concluded, “Kyles was a convenient name for Evans to use since he was known and apparently in regular contact with the” Memphis police. (p. 260)

So what do Wexler and Hancock have to say about all of this? Essentially nothing. They do not mention Hoover's infamous memo nor the unidentified individual who requested Dr. King's room change or even the fact that such a change took place. They make no reference to the testimony of Captain Jerry Williams nor do they note that there was ever a special detail of black officers who were traded for unsuitable white detectives on King's final, fatal visit. They do admit that a “tactical detail of three or four police cars was indeed removed from the motel” but put this down to the request of “an unidentified member of King's party”. (Awful Grace of God, p. 231) When it comes time to answer their own question, “was security in Memphis intentionally compromised?”—aside from a discussion of the removal of black police officer Ed Redditt from the fire station across the street from the Lorraine—the authors have little else to say. However, they do offer the opinion that whatever happened to King's security matters little because “Absolutely none of the standard police security procedures would have stopped a sniper attack from across the street”. (p. 309) Which is just silly. It does not take an expert sniper to understand that the fewer people around the target there are, the more likely the assassin is to have a clear shot. Additionally, having police removed from the immediate vicinity affords the shooter a better chance of escape. But Wexler and Hancock have a response ready for that too: “even Ray eluded capture by avoiding a police officer no more than a minute or two after the shooting”! (p. 309) Not only does this argument commit the blunder of begging the question (which the authors can get away with since they omit reference to the two Mustangs and the statements of Ray Hendrix and William Reed) but it also attempts to use the alleged killer's unhindered escape as proof that the security stripping had no effect on the escape of an assassin! In other words, it was made possible since no security was around. And with that, the reader will agree this silliness requires no further comment.

VII

This review has been very critical but it should not in any way be viewed as a personal attack on the authors. I would not seek to question the integrity of either Stuart Wexler or Larry Hancock. I do, however, seriously question their conclusions and the validity of their approach. It seems quite apparent that the authors were all too trusting of dishonest writers like William Bradford Huie and George McMillan. They therefore accepted a false portrait of Ray—a portrait that was apparently created in no small part by Ray's brother Jerry in his quest for cash—and this in turn led them to begin with a presumption of Ray's guilt. But Harold Weisberg has almost conclusively shown, and I have attempted to convey in this review, that there is no basis for such a presumption. As we have seen, there is no credible evidence to place Ray at the scene of the crime and good reason to believe he left the area a short time before the shooting. On top of this, the forensic evidence does not support a shot from the bathroom and, in fact, a review of the facts demonstrates that such a shot was highly improbable if not impossible.

Hancock and Wexler's belief that Ray took up a bounty being offered on Dr. King's life is simply not supported by any credible evidence. They provide no proof that he at any point heard about such an offer and, in their endless speculation aimed at doing so, try to place him in a bar that did not open until six months after they claimed he was there. Even their most circumstantial peripheral evidence such as Ray's alleged racism or his contact with George Wallace's campaign office is either blown out of proportion or simply without solid foundation. This failure to accurately address James Earl Ray and to convincingly explain his role in the conspiracy is the fatal flaw of "The Awful Grace of God". It is quite clear that, whether the likes of White Knights Imperial Wizard Sam Bowers or National States Rights Party founder J.B. Stoner were involved in the assassination or not, it simply could not have happened the way Wexler and Hancock believe it did.

- The Awful Grace of God Website

- Title of the book, "My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He once wrote: 'Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.' " From Robert Kennedy remarks as he broke the news of King's death to a large gathering of African Americans that evening in Indianapolis, Indiana.