As a young child back in Erie, Pennsylvania I remember spinning a globe at my grandmother’s house and seeing a purple shaded country west of China named Tibet. I thought that was a really ethereal, forbidding name for a nation. As time went on, and I proceeded onto junior high school, high school and college, I saw the name of Tibet less and less frequently on maps and globes. It then seemed to disappear. Instead we got occasional public appearances, usually with celebrities like Richard Gere, by the Dalai Lama, who was billed as the spiritual leader of Tibet. This was accompanied by vague pleas about the independent Tibet movement. Like millions of others, I was never able to put it all together.

The full title of Bruce Riedel’s book is JFK’s Forgotten Crisis: Tibet, the CIA and the Sino-India War. After reading it, I was able to understand what this was all about—at least in a fundamental way. Also, my respect for President John F. Kennedy, which was already estimable, increased a bit more.

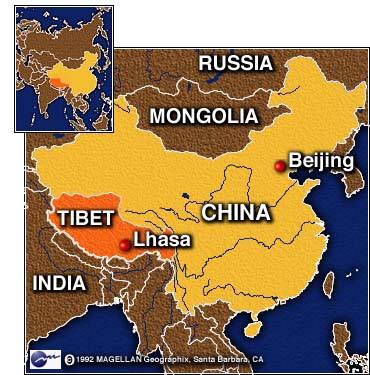

To understand the book, one has to fill in some background about the history of Tibet, that is, why it once existed on maps, and why it does not today. After the collapse of the Tibetan Empire in the eighth century, both the Chinese and the Mongols would occupy parts of it. After the fall of the last Chinese dynasty, the Qings, Tibet expelled Chinese troops and then declared itself independent in 1913. Its capital was located at the city of Lhasa, which was recognized by the British Raj in India. The British also signed a formal treaty as to an India/Tibet border. But the Chinese did not recognize that claim. (Riedel, p. 21)

After the communist takeover of China, and after the Chinese role in thwarting General Douglas MacArthur’s invasion of North Korea and his threat to cross the Yalu River, Mao Zedong decided to take a much more belligerent stance toward Tibet. (ibid, pgs. 14-19) As Riedel notes, at this time, Tibet was really not much more than an impoverished theocracy. It was landlocked, extremely mountainous, and run by Buddhist monks who had little access to the outside world.

Realizing that Tibet posed little problem for the Chinese military to overcome, talks were arranged between the two sides in India, at Delhi. In September of 1950 China proposed a three-stage plan to re-incorporate Tibet into China. While these negotiations were in process, China crossed the Tibetan border with 20,000 troops. The Tibetans were soundly defeated at the Battle of Chamdo in October. India protested the use of force but did not send aid to Lhasa. (p. 23)

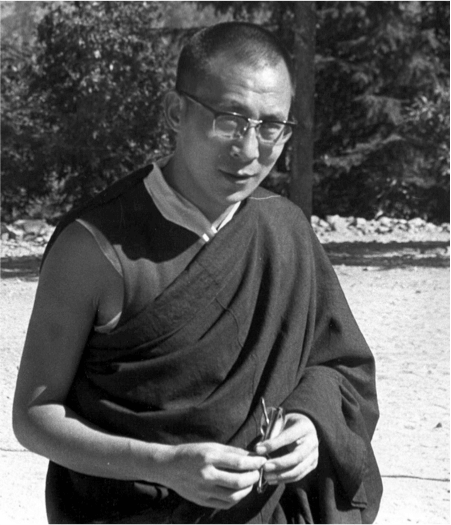

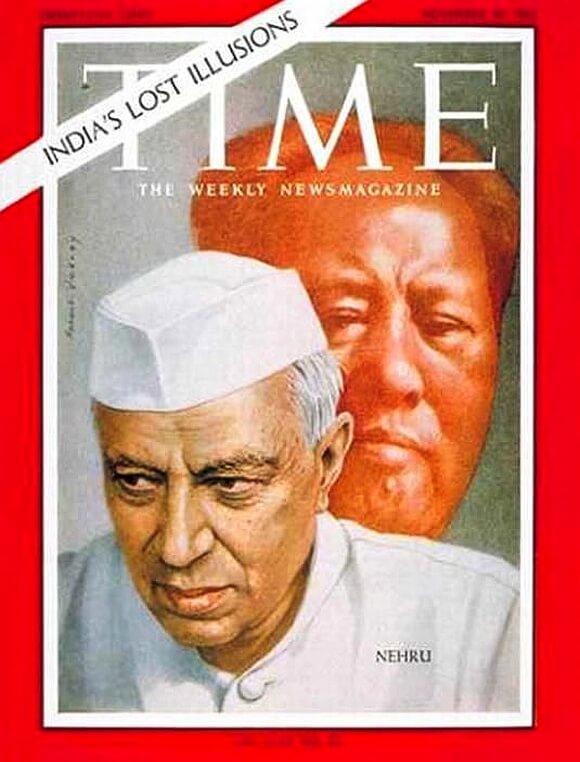

|

| The Dalai Lama in 1962 |

In November, the 15-year-old Dalai Lama—the same man who holds that title today—had just ascended to power. He left for a sanctuary near India at a Buddhist monastery. The American Embassy in Calcutta now opened communications with the Tibetan resistance in Lhasa. The CIA transported the Dalai Lama’s brother to San Francisco to meet with a committee advocating Tibetan independence. But China succeeded in its military operation the next year, and Tibet signed a 17-point agreement making the former country a protectorate of China. (p. 24) The agreement preserved the institution of the Dalai Lama, which was both spiritual and temporal. Therefore, he returned to Lhasa to preside over what amounted to a puppet regime. Nehru, the leader of India, had to accept the arrangement. For China was now the military strongman of Asia, and India was in no position to challenge that supremacy. In a 1954 treaty, Nehru formally accepted China as her new northern neighbor. Nehru’s intelligence chief, B. N. Mullik, did not like the arrangement. The reason being that it replaced a weak and docile northeast neighbor with a strong and truculent one. But, like Nehru, he understood that it was the only solution that was militarily feasible. (ibid, p. 25)

In 1956, the Dalai Lama visited New Delhi. Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai asked Nehru to send him back, promising respect for the 17-point agreement. Nehru and the Dalai Lama parted ways amicably. But the Chinese now made it obvious they intended to transform Tibet from a protectorate into a province. (Ibid, p. 26) A rebellion began in the Kham and Amdo regions. It would eventually spread to Lhasa.

In 1957 CIA Director Allen Dulles decided to begin covert aid to the Tibetan resistance. (p. 31) He began to recruit some of the rebel force, train them in the USA, and then parachute them back into Tibet. In addition to that, the CIA dropped 18,000 pounds of supplies into Tibet that year.

By 1958, Mao and Zhou became aware of this covert effort. They both assumed that Nehru and India were a part of it, which was incorrect. That year, China sent in tens of thousands of troops to halt the rebellion. Tibet asked India for help, but for reasons stated previously, Nehru declined. The Chinese army attacked Lhasa and killed over 4,000 Tibetans. (ibid, p. 32) The army now began to shell the city. Two artillery hits struck near the Dalai Lama’s residence. Suspecting the Chinese were going to imprison him, and with the help of the CIA, in March of 1959 he decided to leave Tibet for India. On the international scene, he now represented what was left of the nation of Tibet.

II

Complicating Dulles’ plan to lend aid to the rebels still fighting for their country was the fact Ayub Khan had taken over Pakistan in a bloodless coup in 1958. Eager to gain favor with America, he joined both SEATO and CENTO, treaty organizations set up by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. He also allowed the CIA to set up an air base in Peshawar for U-2 flights throughout Eurasia. (ibid, p. 35)

|

| Ayub Khan |

Adding to this balancing of interests and aims, China had disputed the Sino/India border in the northeast, an area called Aksai Chin. Nehru considered it part of Indian Kashmir; Mao considered it part of China. Zhou suggested he would trade part of the Chinese Kashmir for Aksai Chin but Nehru declined the offer. Against this tense triangular backdrop, the Dalai Lama was allowed to set up an office and meet foreign dignitaries in the town of Dharamsala. (p. 38) There he met with representatives of the media and decried the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

Nehru began to greatly expand his outposts on the northern border with China. At the same time, the U-2 was used to monitor Chinese military arrangements. In fact, the U-2 Gary Powers was shot down in flew out of Peshawar. Ayub Khan also allowed the CIA to use an airfield at Kurmitola in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) as a staging point for infiltration into Tibet. (p. 41)

The rivalry between Pakistan and India was almost inherent, since they both originated with the departure of the British from India. One became the Hindu state and the other the Moslem state. President Kennedy visited India in 1951. His former tutor at Harvard, John Kenneth Galbraith visited India twice in the decade. After the second visit, he briefed Kennedy about the country.

In the 1960 presidential race, Richard Nixon favored Pakistan and disparaged Nehru. The reason for this was simplistic. Ayub Khan was doing all he could to curry favor with America. Whereas Nehru was a central player in the non-aligned movement— that is, the rather large delegation of nations that wished to stay out of the Cold War, wanting to be free to trade and negotiate with either side without any stigma attached by the other. As historian Robert Rakove noted, that formal organization began with the Bandung Conference in 1955 called by Achmed Sukarno of Indonesia. Along with Sukarno, both Nehru and Nasser of Egypt were there. As were Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. As many have noted, John Foster Dulles disdained this organization, which today includes 120 nations. Because, in his Manichean view, a Third World nation was either with the USA or against it. Kennedy had little problem with the movement or with Nehru since he understood that the health and future of their nations was the major preoccupation of these leaders. Kennedy felt that he could compete with the USSR in this arena by extending aid packages to these countries. Nixon, after his service with the Dulles brothers, thought otherwise. Riedel understands this point. To his credit, he elucidates it by referring to Kennedy’s great 1957 speech in the senate about Algeria. There, he specifically criticized Eisenhower and Nixon over their support for the French colonial empire against the desire of Algeria to be free. (pgs. 47-48)

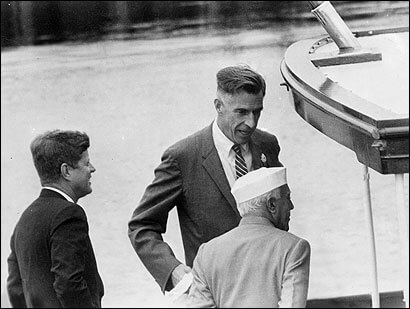

|

| Kennedy, Galbraith and Nehru |

Because of the influence of Galbraith, plus his tolerance of Nehru’s neutrality, Kennedy made a speech in 1959 about the tension between India and China in the Far East. (ibid, p. 50) Galbraith actually had a hand in writing an early draft. He said that China was ahead in this rivalry because of all the financial aid given to it by the USSR. This is why its economy was accelerating faster. He recommended more loans be given to India and also direct foreign investment in order to boost growth. During the speech, he did mention the unfortunate circumstances that had overtaken Tibet, which he referred to as part of the desire of men everywhere to be free. But he did not recommend any path for America to follow in that struggle.

Once Kennedy became president, Dulles briefed him on the covert operations the CIA was running in Tibet. The president decided to continue the action. (p. 57) By 1961, the CIA had performed over 30 drops into Tibet, which amounted to 250 tons of equipment. The drops were getting so large that pilots now used C-130 cargo planes. But since the actual resistance movement was failing to gain traction, the CIA wanted to shift the infiltration point to Nepal. This area housed many more Tibetans who had fled the Chinese onslaught. After consulting with Senators Hubert Humphrey and William Fulbright, Kennedy OK’d the creation of the enclave, codenamed Mustang.

III

In March of 1961, Galbraith had been granted a two-year sabbatical from Harvard. Kennedy quickly appointed him as his ambassador to India. Once approved by the senate, he had to be briefed on the covert operation concerning Tibet. (p. 59) Galbraith did not like it at all. In his view, the aim was hopeless to achieve, and it endangered India. Kennedy kept the program up anyway.

But then Kennedy’s pro-India policy rubbed Pakistan the wrong way. He and Galbraith proposed a billion dollar aid package for Nehru. (p. 62) Khan decided to shut down the East Pakistan part of the Tibetan operation. But after a visit to Washington and a weekend with Kennedy on an excursion arranged by Jackie Kennedy to Mount Vernon, Khan changed his mind. In December of 1961, Kennedy got a resolution through the United Nations in favor of self-determination for Tibet. ( p. 65)

Once Galbraith got to India, he and Nehru became good friends. The ambassador even got India to commit troops to the Congo struggle in Africa. It was the ambassador who convinced Kennedy to propose the billion-dollar aid program Khan objected to. (ibid, p. 69)

In November of 1961, both Nehru and Galbraith visited America. This was to hammer out the details of the aid package. Riedel mentions that during the visit, Galbraith mentioned his objection to the Max Taylor—Walt Rostow report recommending American ground troops being injected into Vietnam. The ambassador grabbed a copy of the report and took it to his hotel room where he penned a blistering rebuttal. (ibid, p. 72) Kennedy read the critique and instructed him to return to India via Honolulu and then Vietnam to prepare his own trip report on conditions in the war theater. Perhaps nothing shows just how confident Kennedy was in Galbraith’s judgment than this mission.

During Nehru’s visit, Jackie Kennedy said she would journey to India the next year. She did so in March of 1962. She spent nine days in the country and then left for Pakistan. After this, and Riedel makes no claim to cause and effect, Nehru began his fateful Forward Policy. This was an attempt to move his border outposts beyond positions held by Chinese troops in the disputed areas. This was provocative, in the sense that violent outbursts now became frequent. But beyond that, Indian troops were outnumbered by a margin of 5-1 in Aksai Chin. And the Chinese had superior weaponry also. (pgs. 87-88)

Riedel believes the Chinese invasion of India in October of 1962 was provoked by 1.) the issue of who controlled Tibet and 2.) Nehru’s Forward Policy. (p. 97) With the former, the Chinese greatly exaggerated Nehru’s aims in Tibet. They thought India wanted to create some kind of neutral buffer zone there. There is no evidence for that idea. But in July of 1962, Mao gave orders to forcefully resist the Forward Policy. The next month the Soviets sold India 12 MIG-21 jets. (p. 102)

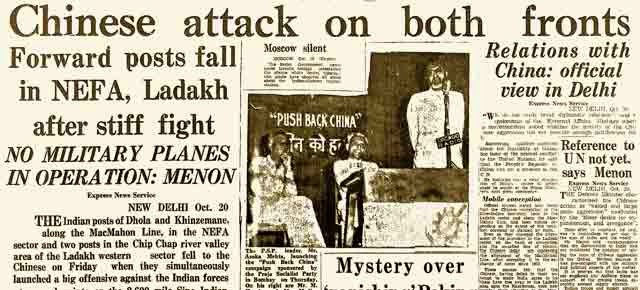

|

The invasion began on October 20th. Which places it just four days after the Cuban Missile Crisis began. Which means that for about nine days, President Kennedy was dealing with both of his major superpower opponents: one in his own backyard so to speak, and one on the other side of the world. Because of the very real fear of nuclear conflagration with Cuba, Kennedy gave Galbraith much leeway in handling the India crisis. Which again shows how much trust JFK had in the man versus the little trust he had with the majority of advisors guiding him on the Missile Crisis. China attacked India on both the west and east borders. At first the invasion was highly successful. After the first week, and with the Missile Crisis declining in tension, Kennedy wrote Nehru to assure him he would back India against China. And his support would be both moral and tangible. Nehru told the ambassador that he would need such support since Russia had backed out of the MIG-21 deal. (pgs. 119-20)

When Kennedy heard this, he decided to get Great Britain to help also. Within a week of this decision, Kennedy was sending eight flights a day across the globe, each loaded with 20 tons of supplies and arms into Calcutta. These shipments got so great that they were eventually boarded on C-130 Hercules cargo planes. The British then got Australia, New Zealand and Canada to also send supplies and arms. (p. 121)

Meanwhile, Kennedy and Galbraith busied themselves with making sure Pakistan did not enter the war on China’s behalf. Kennedy sent messages to Khan advising him to stay neutral during the attack. Nehru also kept much of his army on the Pakistan border to discourage another front from opening. (p. 130)

|

India tried a counterattack on November 14th. It was not successful. India took heavy casualties, especially along the Aksai Chin border. In addition to that, the Chinese were advancing the border outward by thousands of square miles. (p. 133) On November 19th, Nehru wrote Kennedy two letters. He requested air transport for his troops, and jet fighters with radar support. He feared that all of Eastern India would now collapse without the American aid. The ambassador asked Kennedy to instead send both the Seventh Fleet and an aircraft carrier convoy to the area. Kennedy agreed with Galbraith. He sent Nehru a message on November 20th that he would increase the airlift even further, send the Seventh Fleet into the Bay of Bengal and an aircraft carrier to Madras province. Both the ambassador and Kennedy felt this threat would check the Chinese advance.

The next day the Chinese government announced a unilateral cease-fire along the Sino/India border. (p. 140) In the east, they would withdraw from conquered territory, but they would keep Aksai Chin. The Chinese also asked that Nehru stop his Forward Policy and withdraw his troops from the border. India lost over 3,000 men either dead or MIA. Almost 4,000 were captured. (p. 141)

Why did Mao halt the advance? Riedel thinks that China had done enough to humiliate Nehru and teach him a lesson about his Forward Policy. But China did not want to risk bringing American military might into the conflict. (p. 142) Nehru later said that the truce was called because of Kennedy’s decisive action. China may have ended up fighting India, America and England.

IV

After the truce, both Kennedy and Harold McMillan of England sent delegations to India. This combined mission focused on three aims. The first was to increase modern military aid to India. The second was to encourage a solution to the territorial dispute about Kashmir, which was jointly occupied by India, China and Pakistan. The third was to increase the size and scope of the Tibet covert action. (pgs. 150-53)

Kennedy had decided to massively increase military aid to Nehru. The president was so intent on this that he actually wrote out a National Security Action Memorandum. This included creation of six army divisions to guard the Himalayas, funding for increasing munitions creation, and a joint US/UK air defense program. The last included an American/British air exercise over India. (pgs. 151-52)

Concerning the third aim, India now agreed to back the CIA’s Tibet project. In fact, India created its own special force of Tibetans. The CIA agreed to support this militia with its own air force. stationed in the eastern part of India. (p. 158) These rebels were trained by the CIA in Colorado and then shifted to a revitalized operation Mustang in Nepal. Finally, Nehru agreed to let America fly U-2 missions over Tibet. This garnered very good information about the Chinese army occupying the country. All in all, the mission was a boost for both America and India and created a high point for the Kennedy/Nehru relationship.

Unfortunately, Galbraith left India in the summer of 1963. Kennedy did all he could to try and keep him in his administration. But Galbraith really preferred the freedom of tenured academic life over the hierarchical games of the State Department. In fact, he later wrote a satirical novel about his experiences at Foggy Bottom.

|

| Chester Bowles sworn in as JFK's Special Adviser on African, Asian, and Latin-American Affairs |

Chester Bowles replaced Galbraith. As Riedel notes, after Kennedy’s death, the relationship between the two countries cooled. For instance, the massive arms deal Kennedy wanted was delayed twice. Nehru actually died waiting for it to go through. When it did not, his successor went to Moscow to arrange an arms deal. Many Indian officers were now trained in Russia. Bowles was upset about this lost opportunity. (pgs. 162-63)

In 1965, another part of Kennedy’s program was short-circuited. Since there was no movement on the Kashmir problem, Pakistan attacked India over this issue. (p. 164) The largest tank battles since World War II now took place. China did not intervene. Russia negotiated a truce. In 1971, another war broke out between the two rivals. This time, Nixon and Kissinger tilted toward Pakistan. They even urged China to help Pakistan. Partly because they hated the new ruler of India, Indira Gandhi. (p. 169) Ted Kennedy assailed the Nixon/Kissinger favoring of Pakistan in public. India defeated Pakistan and, again, China did not intervene.

Today, India is the largest arms purchaser in the world. China helped Pakistan develop atomic weapons and both India and Pakistan have them today. America’s natural tilt back toward India did not really begin until the presidency of Bill Clinton and then it was accelerated by Barack Obama. The Tibet operation never met with any real success. But since they would have tried it anyway, America decided to help them gain back their country.

I conclude this review with a long quote from the author: “JFK proved to be the ultimate crisis manager in 1962. His deft handling of two global crises simultaneously involving the two great communist adversaries of the United States was a tour de force of policymaking at the highest level. America, India and the world were lucky to have JFK and Ken in 1962.”